The Poker-Faced Enchanter

By ROBERT HUGHES Sunday, Jun. 24, 2001

THE IMAGES AND IDEAS OF RENE Magritte are known to millions of people who do not know him by name. So argues the art historian Sarah Whitfield in her catalog to the retrospective of 168 works by the great Belgian Surrealist that opens at New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art this week, and she is certainly right. This accounts for the faint feeling of deja vu that even non- Magritteans sometimes get when looking at his work. Magritte died in 1967, but for the best part of a half-century his images -- or variants on them -- have been used to advertise everything from the French state railroad system and chocolates to wallpaper, cars and political candidates.

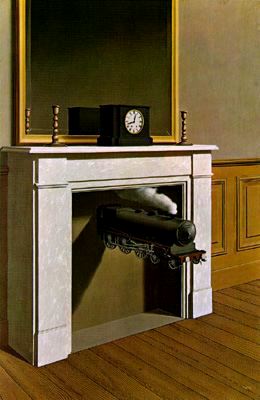

The advertising industry has had a vast effect on modern art, but no modern artist has had more effect on advertising itself than Magritte. Yet there is never the slightest feeling that his work has been corrupted by its commercial reuse, and this is because of its clarity and intelligence. Magritte's paradoxes still slice cleanly. No matter how many times you see the small locomotive steaming from the living-room fireplace in his Time Transfixed (1938), with the mantel clock pointing to 12:43 and every grain line in the wooden floor in place, it will still come from behind its utter familiarity and surprise you.

Time Transfixed- 1938

The history of modernism is suffused with cults of artistic ego and rampant "originality" -- especially Surrealism, the movement Magritte was linked to. But he made a virtue of anonymity, disappearing behind the work like one of the partly vanishing, ambiguous figures in his own paintings. Apart from a short stay in Paris (1927-30), Magritte spent his whole adult life in Brussels, issuing his mind-wrenching visual conundrums from a base of the most perfect bourgeois propriety, using a corner of his living room for a studio and never painting any naked woman but his wife Georgette, who, in return, never posed for any other artist. The common man in Magritte's paintings, with his raincoat and bowler, whether standing with an apple in front of his face or floating down in multitudes upon the unperturbed streets of Brussels, really is Magritte -- the poker-faced enchanter. No artist ever behaved less like one.

It mattered a lot that Magritte was Belgian, not French. The French Surrealists made a point of public provocation, inserting themselves into politics, issuing pretentious manifestos. Not so their Belgian cousins; "the subversive act," said one, the writer Paul Nouge, "must be discreet." Magritte's style, as it evolved, was studiously neutral. His early work, in the 1920s, was mainly exercises in late Cubism -- the "tubist," streamlined, geometrical forms of Fernand Leger and Amedee Ozenfant, shapes that might have been made from metal. The artist who clearly had the biggest impact on Magritte, turning him toward fantasy and irrational images, was Giorgio de Chirico. And even then Magritte couldn't find a way to use De Chirico's unique scenography until he learned about collage from Max Ernst.

The objectivity of collage -- taking an image from outside and putting it, whole and entire, in the fictional space of the painting -- appealed to Magritte, because he liked standardized images; it was their encounter and rearrangement that created the magic, more than the things themselves. "Our secret desire," he remarked, "is for a change in the order of things, and it is appeased by the vision of a new order . . . The fate of an object in which we had no interest suddenly begins to disturb us." Turned balusters, game pieces, the little round horse bells known as grelots, cut-out paper doilies, wood paneling, views through a window, fire, a birdcage, a rifle, a tuba, a pipe, loaves of bread, a naked woman: there wasn't much in Magritte's repertoire of images that couldn't have been seen by an ordinary Belgian clerk in the course of an ordinary day.

But assembled they are another thing -- just as Ernst's drawings made of rubbings from the floorboards of his seaside hotel became another thing. Here is the silent ugly cannon in the room of screens, each bearing a familiar image; in a second it will fire of its own accord, blowing the screens to shreds; we stand, as the title says, On the Threshold of Liberty. Some of Magritte's images have taken on, with time, a truly prophetic aura. One of these is Eternity (1935). Three pedestals in a museum, with a red rope stretched in front of them. On the left one, a medieval head of Christ. On the right, a head of Dante. In the center, a block of butter. A jab at the contented Belgian stomach, 60 years ago; but today you can't help thinking of the lumps of fat by Joseph Beuys that are enshrined in the world's museums, as though Magritte had been conducting satire in advance.

He painted in a perfectly deadpan style, neutral rather than "primitive" -- serviceable, in a word. It came partly from posters and partly from kitsch art. "This detached way of representing things," he remarked, "seems to me to suggest a universal style, in which the quirks and little preferences of an individual play no role." It is meat-and-potatoes figuration, with no pretensions; if there were any pretensions in this world, where flotillas of loaves sail by in the evening sky like flying saucers and an innocent eye opens in the middle of a slice of ham on your plate, they would greatly reduce its credibility.

But the epigrammatic force can be irresistible, especially where Magritte reflects on sexual violence, alienation or loneliness: the couple trying to kiss through layers of cloth in The Lovers (1928), or The Titanic Days (1928), his image of attempted rape, in which the bodies of the terrified woman and the attacking man are fused together as in a grim photographic overlap. Often his color is extremely beautiful, though the viewer, intent on the visual conundrums, may not at first notice how powerful and tender it can be. But as his friend Louis Scutenaire wrote, "Magritte is a great painter. Magritte is not a painter." He had no interest in what the French called la belle matiere, and when he did essay it -- as in a series of pseudo-pastoral kitsch- classical paintings in the manner of Renoir, done during World War II -- he subverted it; these hot, sluglike nudes are of a brutal vulgarity exceeded only by late Picabia, who may in fact have influenced them.

In some ways his most extreme work comes from this aberrant moment of peinture vache (stupid painting), as he called it -- it's as though, in parodying other Belgian artists (Ensor, and a particularly gross comic illustrator named Deladoes), he touched a demotic rock bottom from which he could only recoil in the end. But Georgette hated the new style, and by 1950 Rene was back to the old one, often repainting versions of images he had first made in the '30s. This recycling fitted his own idea of himself as a craftsman rather than an artist. You could make more than one chair to the same pattern.

Magritte was not a "literary" artist, and his work was more about situation than narrative. Nevertheless, his titles were important to him, and they are never neutral. They were, so to speak, pasted on the image like another collage element, inflecting its meaning without explaining it. They reflected his browsing in high and popular culture. The Glass Key comes from Dashiell Hammett, and references to the Fantomas thrillers (on which Magritte, along with the rest of the Surrealists and everyone else in France and Belgium, doted) are everywhere. On the other hand, The Man from the Sea is Balzac's title, and The Elective Affinities Goethe's.

Then there was Edgar Allan Poe. Magritte used him repeatedly. The Domain of Arnheim, Magritte's image of a vast, cold Alpine wall seen through the broken window of a bourgeois living room, with shards of glass on the floor that still carry bits of the sublime view on them, is the title of Poe's 1846 tale about a superrich American landscape connoisseur who creates a Xanadu for himself. "Let us imagine," says Poe's hero, "a landscape whose combined vastness and definitiveness -- whose united beauty, magnificence and strangeness shall convey the idea of care, or culture . . . on the part of beings superior, yet akin to humanity . . ." Yes, one can well imagine Magritte liking that. His work too sets up a parallel world, extremely strange and yet familiar, ruled by an absolutist imagination.