Here's an article on René Magritte's 1927 painting Swift Hope (L'Espoir Rapide):

Magritte, René: L'Espoir Rapide (1927) By Tom Lubbock

Friday, 25 November 2005

You know the scene. An old soldier is replaying a favourite battle on the breakfast table. 'We were here,' he says and puts the sugar bowl in the north-east corner, 'Jerry was here', and the marmalade is recruited, 'the Yanks were here', a china plate, 'the village was over here', a cereal box is laid flat, 'and the river' " spoons and forks are arranged into a trailing line of silver " 'the river was here...' etc.

And you know how this scene usually ends. The old buffer becomes excited and muddled. He forgets what stands for what. Other utensils, that haven't been allotted any part in the scheme, get drawn in.

It's a story about representing. In order to re-enact his battle, the man improvises a very rudimentary, and therefore fragile, form of representation. One thing stands in for another very different thing. There isn't any likeness between the two things, nor any established link. Consequently his scheme can easily break down into confusion. It's only a first step towards image-making.

But there is some likeness. A pot of marmalade may not look much like a unit of German troops, but in several ways the tabletop does resemble the battlefield. The relative sizes of the stand-in objects are roughly right. So are their basic shapes " the village is a compact form, the river is long and thin. And the spatial relationships between them are certainly meant to be accurate.

You can imagine the level of likeness being raised " or reduced. The stand-in objects could be made to correspond more and more closely to more aspects of the things they stand for. Alternatively every element of the battle, even the river, could be represented by an identical tea- cup. That would be a very minimal scheme. It would carry just two kinds of information. It would show the number of distinct items that were involved, and it would show their layout on the ground.

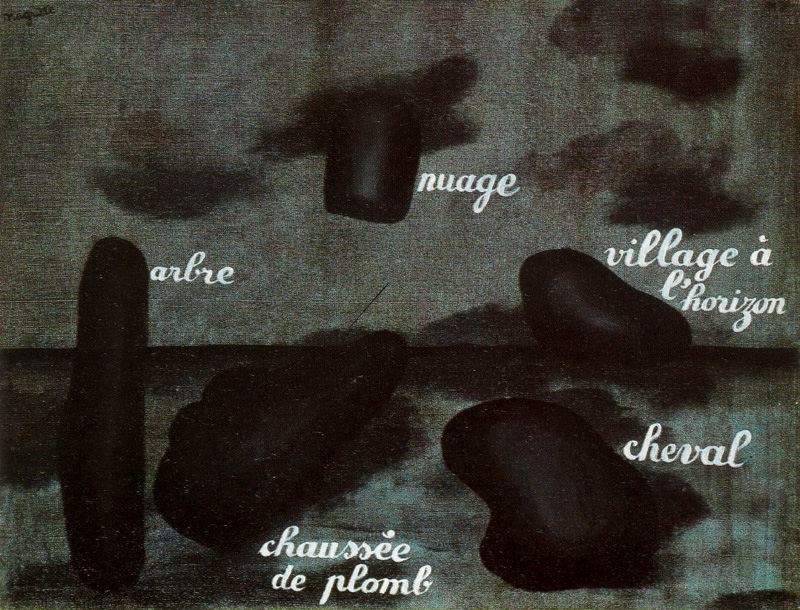

Magritte's L'Espoir Rapide (Swift Hope) makes a similar reduction. It offers a very inarticulate image, just about the minimum that will qualify as a pictured scene. And to emphasise the point, Magritte labels the image with some paradoxically specific words. But ignore the white labels for the moment. Concentrate on the deep-blue scene. How inarticulate is it really?

It's not a complete mess. It shows five clear elements, five rounded forms, with distinct shapes and different sizes. They have a hint of solid volume, a lighter patch swelling out of the middle of each one. You can't say precisely what they are, but they're not just anything. They're definitely something blobby " like megaliths, or inner organs, or amoebae.

You can say more. The long thin one is standing upright. Three are lying on the ground at various distances. The small one is off the ground. In other words, the scene doesn't only consist of these five blobs. It situates them within a view and a three-dimensional space. L'Espoir Rapide has the same spatial structure that you find in many pictures. It divides into two parts. Below, there's a ground level; above, there's a backdrop.

It is the standard picture stage-set, a template that's used in various types of scene. In a landscape, it corresponds to the surface of the earth, stretching to a horizon, with the sky beyond. In an interior, it is the floor of the room, meeting the back wall. In a still life, it is the table, and the wall behind it. The content changes, but the structure remains, and within it objects can be located as near or far, on the ground or in the air.

And Magritte's apparently elementary image holds another kind of information: shadows. Each of the five blobs has an area of darkness behind it that registers as a shadow cast on the adjacent surface. These bits of shadow aren't put down very precisely or consistently. There are isolated dark areas that aren't near to any object. But the effect is enough to stick the blobs to the ground they sit on, to make them seem more solid, to create a sense of dim light-fall.

Even without the labels, you'd probably have an idea that this scene was a landscape. And when you read them, what they declare isn't so paradoxical. Tree, lead road, horse, village on the horizon, cloud: the words correspond pretty well to the shapes and sizes and positions of the five blobs. The tree is a tall thing. The horse-form almost has a head. The village is indeed on the horizon.

True, it's weird to have a road represented by a long solid object, but it points away into the distance as a road might well do. And the cloud is funny, being such an abrupt lump, and apparently casting a shadow on the sky, but it's where a cloud should be. There isn't a sharp disjunction between the things and what they're meant to stand for " rather less sharp, actually, than in the breakfast battle scene.

L'Espoir Rapide is like a world in embryo. It feels thwarted and straining, a nocturnal, pupal landscape where things have not yet emerged into their destined identities. It's like Alexander Pope's lines about 'the Chaos dark and deep,/ Where nameless somethings in their causes sleep'. But Magritte's somethings are not quite the forms of things unknown. You can see how these blobs could fulfil their waiting names. They just need licking into shape. By contrast, the title of the picture is utterly baffling.

THE ARTIST

René Magritte (1898-1967) is a paradox. The Belgian surrealist, popular and influential, is the straight man who painted bizarre scenes in a deadpan manner. But he makes sense. He couldn't paint very well, but his work is a sustained exploration of the language of images. He's always making a point about how pictures work and how strange pictures are.