Friends of Magritte: Edward James

Edward James was an eccentric poet, collector, and patron of both Dalí and Magritte. Edward James became an important figure in Rene Magritte's life for a short period of time from 1936-1938. James would remain friends with Magritte for many years but his role in 1937 and 1938 was paramount. Here's some background information:

In the summer of 1935 James, while visiting with the painter Jose Maria Sert and his wife, met Salvador and Gala at their home in Catalonia. Dali, Gala and James became close friends and Dali was invited to London to help decorate the Monkton house in Chelsea with surreal furnishings and paintings. Through an introduction to James from Dali and others plus Magritte's participating in the 1936 International Surrealist exhibit, Magritte also was consulted about contributing paintings to the interior design. James remained an important supporter and collector of Magritte's work and Magritte stayed with him in London for five weeks.

.%201937.jpg)

The Pleasure Principle (Portrait of Edward James) 1937

Magritte's patron and friend ELT Mesens became the Director of the London gallery and in the summer of 1936 helped organize the "International Surrealist Exhibition." Magritte, whose work was displayed prominently at the exhibit, then received a commission from Edward James to do three large paintings for James' house on Wimpole Street. The paintings were two portraits (above and below) and a new version of "On a Threshold of a Dream." In January 1937 James invitted Magritte to stay at his house for a month or two and complete the paintings. James offered Magritte 250 pounds, comparable to what he was paying Dali for his paintings.

In February 1937 Magritte and Mesens traveled to London. The five week stay went well, James introduced Magritte to Henry Moore and Matta. According to Sylvester, "(James) did not enjoy the society of Magritte, who was rather uncouth for his taste; he adored Dali." When Magritte returned to Brussels, James also commissioned three new versions of Magritte's older paintings "The Poetic World," The Red Model" and "Youth Illustrated."

Magritte apparently thought James was going to be his new wealthy patron. Rene wrote James in 1938 offering to do more paintings in exchange for a 100 pounds a year fee. James declined Magritte's offer and though James continued to buy several of Rene's paintings including his 1939 "The Glass House," the thrust of Edward's patronage of Rene was over. James did promote Magritte's work and kept in touch with him during the War years (1942-1945).

Here are two articles on James, one by Deirdre Fernand and one by Michael Kernan:

The Truth About the Man With No Face

The Sunday Times February 25, 2007 By Deirdre Fernand

He was the Saatchi of surrealism an eccentric British millionaire who supported the wildest avant garde art. So why do we know so little about the man who was a close friend to Dali and subject matter for Magritte?

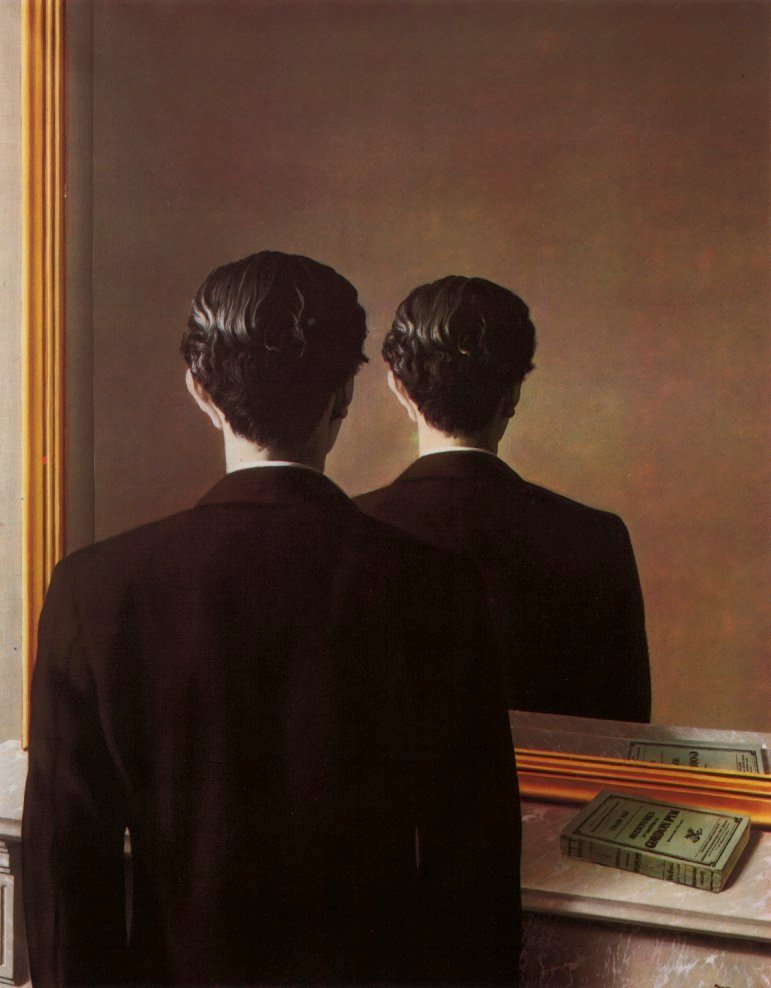

Magritte: Reproduction Prohibited (Portrait of Edward James) 1937

Like so many eternal egoists and deluded despots, the artist Salvador Dali loved to refer to himself in the third person. It was always “Dali this” and “Dali that”. As a means of self-promotion, it worked – the world soon acknowledged him as the genius he always knew he was. “Every morning when I awake the greatest of joys is mine: that of being Salvador Dali,” he wrote in his autobiography. The Spanish creator of the soft watch and the lobster telephone, two of the most famous surrealist images in the world, always maintained that “if you act the genius, you will be one”.

As much as he loved himself, he loved fame and money. No wonder a fellow artist, André Breton, came up with a fitting anagram of his name, Avida Dollars. Other kindlier spirits knew him just as Señor Patillas, or Mr Sidewhiskers, after his trademark twirly moustache. But to Edward James, the Englishman who helped create Dali, he was always “mon cher” or Petitou, their pet name for each other. Their intense friendship kick-started Dali’s career. Both men were born just after the turn of the century and became fabulously wealthy. But while Dali became one of the biggest names in 20th-century art, along with Picasso and Matisse, Edward James has been all but forgotten. This British millionaire, patron and collector was one of the true begetters of surrealism. The movement, which draws upon images from the subconscious, is based on the belief that there are treasures hidden in the human mind. James himself, who died in 1984, was a hidden treasure. Without the support of the bankrolling Brit – the Charles Saatchi of his day – Dali as we know him today wouldn’t have existed. James’s patronage extended beyond Dali to René Magritte; his encouragement, to a circle that included Joan Miro, Man Ray and Leonora Carrington.

James remains an enigma. Though he was rich and eccentric enough to indulge every whim, he didn’t seek the limelight. Unlike Dali, he did not throw furniture out of shop windows when the display angered him, nor get himself arrested, nor make headlines after being burnt in his bedroom. But what was his exact relationship with Dali? How much did they collaborate? Compared with the crazed Catalan, James was a blushing wallflower.

The Real Face of Edward James (photo manipulation)

A new exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum seeks to drag this relatively obscure figure – the British father of surrealism – from the shadows. Alongside paintings from his collection will be some of the most famous objects ever produced, including Dali’s lobster telephone, commissioned by James for his London house, and a lips sofa that Dali designed, inspired by a poster of Mae West’s pouting lips. Two such sofas were destined for his country house, Monkton, in West Sussex. Other works, over 300 in all, have come from around the world. Many of them, including Meret Oppenheim’s Table with Bird’s Legs, and Dali’s Chair, where the back is fashioned from two hands, have never been exhibited before in Britain.

If James is largely unknown to the public, it is perhaps his own fault. One of the most famous images created by René Magritte, La Reproduction Interdite (above), shows a man looking into a mirror – and staring at the back of his head. Weird and unsettling, this portrait manqué (missed portrait) is all that surrealism should be. The man in the picture – the man without a face – is Edward James.

“We owe him a huge debt,” says Ghislaine Wood, curator of the exhibition and a 20th-century expert at the V&A. “Not just for encouraging and funding Dali, but for creating a climate in which the avant-garde could flourish. And he helped contribute to the cult of artist as personality. Without Edward James, without Dali, there would have been perhaps no Andy Warhol.”

James described himself as a poet, but poetry never brought him fame. A friend of Sir John Betjeman and Evelyn Waugh, he remained in the background, the man who enabled other artists to be themselves. It was not always a happy position. He was as rich as any Rockefeller, but his money did not buy him contentment. He suffered a miserable marriage and a divorce that cost him millions in alimony – and his good name. Like a gilded butterfly, he was always flitting from project to project. “I dissipated everything,” he once said. “I could fulfil every kind of whim.” His friend Desmond Guinness, another patron of the arts, put it more kindly: “All his life he got sidetracked.”

But with what results? Born in 1907, James entered an Edwardian world of almost limitless wealth and luxury. The only son of an Anglo-American family, his fortune came from railways and timber. A distant cousin was the novelist Henry James. His father died when James was five, the estate passing into trust until his majority. At 21 he inherited £1m from his uncle; at 25, the West Dean estate in West Sussex – a 19th-century gothic-style mansion, with 6,000 acres, farms and a village. Also good-looking, James was one of the most eligible men of his day. But he was destined in the eyes of his family to be a disappointment. A poet in the family? Whatever next? And what did he mean by “aesthete”, anyway? He could neither play the country gentleman nor was he interested in marrying well.

“I’ve tried to conform as much as possible,” he said in a television interview two years before his death. “One is an eccentric against one’s own will… [It is] something that one is born with.” So what motivated him to embrace the avant-garde? As his friend the art dealer Christopher Gibbs reminds us, James took pleasure in rejecting the values of his class. He embraced the bohemian art world with all the alacrity and expansiveness his wallet allowed. “I think he and Dali were two eccentrics who found each other,” he says. “They were a weird brotherhood. James was rebelling against his conventional narrow background.”

He found his family and their aristocratic circle dull and snobbish. He remembered one tiresome aunt describing a gathering: “What a mangy party. Only one viscount and one baronet.” The Jameses, with their house parties, were at the centre of royal life. Edward VII, James’s godfather, was a frequent visitor. Many people thought that James’s mother, Evelyn, was his mistress. James would always dismiss this. He believed his mother was Edward VII’s illegitimate daughter – thus his godfather was, to him, his grandfather.

The young James saw little of his mother, who remained aloof, as stiff as her corsets and encrusted with jewels. In contrast, his nurse was “nice and comfy and soft”. He once talked about his mother’s apparent lack of maternal feeling. He described her wanting one of her five children to take with her to church and calling upstairs to the nanny to give her “one that goes best with my blue dress”.

James hated Eton, and it was not until he went up to Oxford that he began to mix with like-minded people such as Betjeman, Waugh and Harold Acton, the aesthete and writer. These were the years that Waugh would later commemorate in Brideshead Revisited. While other undergraduates had peeling paint, James lined the walls of his rooms with silk and 17th-century tapestries. His curtains were a red William-and-Mary design.

His aim was to bring the marvellous into everyday life. He had the imagination, the intellect and the fortune. “Money seemed to me to have been given to spend… but I was not going simply to give it away to some uncreative institution called a charity,” he once wrote. “I felt I could do more to alter the face of the world, more to usher in that new world, by spending it in my own way – in particular, by fostering any and all creative spirits I could meet with…”

No wonder his mother, worried out of her mind, wrote to James’s agent, in capitals, that he should tell him to “CUT OUT MUSIC AND WRITING POETRY”. She quashed all creativity; she wanted him to concentrate on his degree, his future at West Dean, and enter parliament.

But if James’s money was a blessing, it was also a curse. Many of his peers viewed him as a rich kid playing at being an artist. The poet W H Auden was one who dismissed him as a dilettante. After all, here was a man who could get into a private plane to loop the loop, and throw the silliest parties in college. For one prank with Betjeman, he invited every Mr Bottom in Oxford to a party. He took endless pleasure when Mr Sidebottom, Winterbottom, Longbottom and plain Mr Bottom met for drinks, then realised why each had been invited. Later, on his travels, he booked a suite for himself – and a set of rooms for his pet boa constrictor.

James’s snobbish mother had always warned him against marrying an actress: an uncle was disinherited for marrying a chorus girl. So relations with his family deteriorated when he fell in love aged 24 and married an Austrian dancer, Tilly Losch. He adored her beauty and artistry; she appeared to adore his bank balance. By all accounts, she believed him to be homosexual and was surprised to find out on their honeymoon that he wasn’t. Like his mother, she was cold and remote; he tried constantly to please her. He engaged the painter and designer Paul Nash to remodel his London house, and installed a barre for Losch’s ballet exercises.

Tilly Losch 1928

"Always have a good little black dress, pearls, and stay in the best hotel, even if you can have only the worst room," said the dancer, actress, and femme fatale Tilly Losch (1907-1975).

He was already moving in artistic circles, meeting Dali in France in the mid-1930s. But it was at Monkton, the hunting lodge on the West Dean estate, that his greatest surrealist fantasy was realised. More than 70 years after Monkton, now in private hands, was given the James-Dali treatment, it is still a shock to come upon this violet house sitting on the South Downs. It remains the most important three-dimensional surrealist creation in Britain. James took a hunting lodge designed for his father by Sir Edwin Lutyens and, with Dali, gave it over to his wildest dreams. The sedate brick-and-tile box was now purple and green. The chimney stack was transformed into a clock tower showing the days of the week, not the hours, and plaster aprons were placed under windows, like sheets being aired. Dali suggested drainpipes that looked like bamboo, and palm-tree columns to flank the doorway. As Freud, whose theories of the unconscious influenced the surrealists and who met Dali in 1938, said, “A hero is a man who stands up manfully against his father and… overcomes him.” The Freudian implications of James revamping his father’s house – and marrying an actress – cannot be ignored.

Inside, it was just as eccentric. James had wanted a drawing room with walls that flopped in and out like the inside of a dog’s stomach. Fortunately, or not, he thought better of it. Still, he did choose a migraine-inducing jazzy print for his hallway. For his study he had blue serge, inspired by his favourite suits. And his bedroom was dominated by a canopied bed modelled on Nelson’s funeral hearse. In the dining room were two huge Mae West sofas. “The basic drawing for them came from Dali but it was James who realised them,” says Wood. Their collaboration also produced a magnificently mad tea service for Royal Crown Derby, now in the V&A.

And, in homage to his wife, James had a carpet woven with her footprint. If the other touches were brilliant folly, this was foolhardy. His marriage was a disaster. Losch terminated pregnancies by him, and had lovers, including Randolph Churchill, Sir Winston’s son. He eventually ripped up the carpet, replacing it with one bearing the footprint of his favourite wolfhound. “A more faithful friend,” he is said to have remarked. But his wife continued to obsess him. He spent £50,000 on a season of ballets for her to star in. He even invited Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill to London to compose an opera in which she could dance. But nothing could make her love him.

Replacing a footprint with a paw print could not have been easy, a graphic reminder of unrequited love. But the end of the marriage brought a certain liberation. Had the couple enjoyed a traditional life, with children, James’s prodigious creativity may have been spent elsewhere. Now he was free to pursue his interests. In 1936 he helped bring Dali from France to London for the first surrealist exhibition. The artist chose to address the gathering in a diving helmet, to show he was “plunging down deeply into the human mind”. But at the end of his speech, when he came to remove his headgear, it got stuck. Starting to panic, he could not breathe. “It was James who came to his rescue,” says Sharon-Michi Kusunoki, the archivist of the Edward James Foundation at West Dean.

The pair continued their intense collaboration. “James had first refusal on all Dali’s work,” she explains. “And he made sure all the artist’s needs were met. Not only was he paying him, he was also buying the latest fashions, such as Schiaparelli dresses for Dali’s wife, Gala. It’s important not just to see him as a rich eccentric but as a catalyst and mentor for Dali.” As a token of his friendship, James sent the Spaniard a stuffed polar bear for his Paris apartment.

James was fast earning recognition as a sympathetic and generous patron. He knew everyone, such as Miro, Max Ernst, Paul Eluard, whose wife, Gala, left him for Dali, and he had struck up a relationship with Magritte. People were curious, wanting to know who the rich Englishman was who could fritter away £50,000 on wooing back his wife. However, James finally chose to escape his marriage, suing Losch for divorce on the grounds of infidelity in 1934. But that spelt the end of his life in Britain and, eventually, his collaboration with Dali. In 1930s Britain, gentlemen did not damage a lady’s good name, however provoked. Polite society shunned James, and England was never his home again. In 1939 he left for the US – in Taos, New Mexico, he lived among a community of artists that included D H Lawrence and his wife, Frieda.

Dali, who had also moved to the US, would play no further part in his life. Indeed, documents in the archive at West Dean, now a college for arts and crafts, reveal how disillusioned James had become by Dali’s showmanship; he disapproved of his politics and avarice. The artist had continued to prosper under Franco’s fascist regime. A letter written c1945 to Dali, found by Dr Kusunoki among James’s papers but possibly never sent, is profoundly critical. “In the past I often heard you speak with bitterness and contempt against greed and opportunism in others,” he wrote. “Do you realise that you have yourself become in the eyes of everyone who knows you well – and very nearly to the general public also, by now – a monument of this greed, opportunism and bad taste which you used to scorn.” Dali, for his part, was being feted in the States. He did not need his old supporter.

It was not until the late 1940s that James found peace in the Mexican jungle, creating a surrealist garden, Las Pozas, in Xilitla, in a clearing. Here he indulged his passion for orchids and adopted a local family. He built a “stairway to imagination”, as he once put it, in plant and stone. He died in 1984, and his body was brought back to be buried at West Dean. That same year, Dali was burnt in an accident at his home in Spain. He died of heart failure in 1989.

When James’s art collection came to be sold, nobody could believe how much he had amassed. He had bought his first painting at 18 and by the time he died he had the best by Ernst, de Chirico, Man Ray, Miro, Picasso, Magritte, Duchamp and, of course, Dali. An art dealer, Julien Levy, who knew him well, viewed him as a champion who was “fabulously rich, generously constructive and annoyingly wilful”. But Dali, his old sparring partner, saw him differently: “Edward is as insanely relentless as me.”

Edward James: One man's fantasy stands tall in a jungle in Mexico

by Michael Kernan

We jounce for five hours in a pickup truck heading west from Tampico over the dusty Mexican plain to the Sierra Madre, up and up into a green world-peaks as sudden as the mountains of Moorea, tree-covered jagged ranges huge enough to be the molars of God, past coffee plantations, ramping bougainvillea, banana trees, crashing streams-and on to the very top, through the steep hilltop town of Xilitla to reach at last the hidden city that Edward James, the eccentric British Surrealist, built in the deepest jungle, a swirling dream in concrete, a fantasy of shapes that marries Gaudi, Escher, Borromini, Simon Rodia and the Emerald City of Oz.

With my guide I slip through the gate of this amazing place, called Las Pozas after its nine pools strung along a winding jungle river, connected by waterfalls. I climb a 20-foot concrete cactus, Up freestanding steps to a mushroom platform, up again on spiraling stairs that finally wind themselves around the great shaft and disappear. Enormous fluted columns all around. Eight-foot walls with teal shaped holes, a moongate, a path bordered by erectile mosaic serpents. Great gates framed in wrought-iron stars. Concrete leaves big enough to walk on, bulbous concrete flowers in yellow, red, green, blue, white, purple. Gourd shapes. Calabash shapes. Dolphin shapes. Stairs that lead straight up into space and stop. With its raw concrete patinaed by green mildew, rusting corrugated steel and neglected stretches of fence bent by fallen trees, Las Pozas feels like a Sleeping Beauty castle arrested in time before it was quite finished.

A gazebo here, and close by, a tiny apartment four stories up with glass windows, two freezers, a fireplace, archways, glass bricks and a collection of perfume bottles. Ferns everywhere, lianas, thickset trees, all so intertwined with the constructions that it is impossible to tell where the jungle leaves off and the invention begins. Tucked into the steep hillside, I find a storeroom crammed with the beautiful wooden molds made by local carpenters for all these fantastic shapes. Also James' four-man sedan chair. And a stone hand nearly as tall as a man. Beside it, a nine-foot dome, almost an Olmec head, beset with columns that blossom out on top, and more bamboo-like columns, so delicate that they quiver when a bird takes off from them. Some of the fantasies have names: the House With a Roof like a Whale, the House With Three Stories That Might be Five, the Stegosaurus Colt , the Fleur-de-Lys Bridge and Cornucopia, the St. Peter and St. Paul Gate, the Temple of the Ducks, the House Destined To Be a Cinema.

The waterfalls, especially the biggest one, more than 80 feet high, are embellished with platforms, curving walls, flying buttresses that may hold up the entire hank or may do nothing at all, battlements, mysterious little prows jutting into the pools. The lower pools have diving boards and small sandy beaches for the local people who come here to swim.

Everywhere, underfoot and up wall corners and winding around concrete bamboo screens, I see electric conduits. In 1979, when the place was as nearly complete as it ever would be, James had lines brought in from Xilitla and lit up the mountainside like a fairyland every night.

Talk about magic. Everyone in town came to see. Las Pozas was locally famous, of course. It had been abuilding since 1949, and from 1962 on, employed as many as 150 workers at one time. By the time he died, in 1984, James had sunk millions into the project. Here and there, snug among the six-foot-thick columns (designed eventually to support enormous planters and an aviary) and barrel vaults and groined arches and framed windows, I noticed all sorts of cages. A little aviary for parrots and flamingos, a screened cage for the ocelots, a deer corral, a two-story room for small monkeys, a turtle pool, a 20-foot concrete pool shaped like a human eye, its pupil five feet across. This was where the crocodiles often played, our guide mentioned casually.

Edward James adored animals. When he visited Mexico City he always stayed at the elegant but modest old Francis Hotel or the Majestic, because they let him keep his animals there. Once a guest complained that there were mice in the hotel. She was sure she had seen one in the hall. The manager replied, "Oh no. They're not the hotel's mice. They belong to Mr. James in the room next to yours. He feeds them to his boa constrictors."

James often wandered through his jungle home with a parrot perched on his shoulder. Once he showed a young friend how his beaky nose and pointed chin were growing closer together. He said, with a certain complacency "I am turning into a parrot, you see."

Las Pozas is strange, but not half as strange as its creator. His American grandfather, already a millionaire with vast timber holdings, married into the mining wealth of the Phelps Dodge family before moving to England. . One of his three sons, who made his career as the master of West Dean Park and its 6,000 acres in Sussex, married an Englishwoman who was reputed to be an orphaned daughter of Edward Vll.

Edward James was born to them in 1907, into a world of nannies and shooting parties, shuttled seasonally between West Dean, his parents' London town house in Bryanston Square and a summer place in Scotland. He went to Eton, and hated it. At Oxford he had a Rolls-Royce and a silk-lined room worthy of a Sebastian Flyte, and he soon drifted into the gilded London society of Sitwells, Mitfords and Cunards, of Noel Coward and John Betjeman, of Agustus John and Randolph Churchill.

A charming person, Edward James, a wonderful raconteur and a lover of parties. His hermetic childhood left him curiously innocent about the world of work. And impulsively generous: once when a friend wanted to borrow his car, he gave it to him. But then a reaction - "They want my money, they want my blood"- and he would retreat into introversion.

He was a packrat who never threw anything away, and so obsessively fastidious that he would boil up a saucepan full of old paperclips, drenched in cologne, for reuse. Named to a diplomatic post, he almost caused an incident through his insouciant mistranslations and was fired. He wrote poetry and printed it himself, wrote a novel or two, fell in with avant-garde artists and then, in 1928 met Tilly Losch.

She was dancing in a Noel Coward revue but was celebrated more for her sinuous, wanton beauty than for her dancing. She filmed a performance piece that featured her lovely hands sinuously interlacing to Bach's "Air on a G String". James married her. He was 24. Soon it turned out that she had fancied a marriage in name only (it happened in those days). She involved herself in a series of increasingly visible affairs, including a primal scene on a sofa with Randolf Churchill witnessed by a maid, and finally left him. To get her back James financed George Balanchine's first company, Les Ballets 1933, paying for three ballets for her, including the landmark Brecht-Weill collaboration "The Seven Deadly Sins," performed by Tilly Losch and Lotte Lenya, and another ballet with music by Darius Milhaud and sets and costumes by Andre Derain.

It was no use. Tilly sued for separation, charging homosexuality among other things, whereupon James scandalized everyone by countersuing, accusing her of adultery with Prince Serge Obolensky. Astonished and wounded by the outcry, for this simply was not something a gentleman did, James moved to Europe for a while.

James with his wife Tilly Losch

There he met Salvador Dali [summer 1935] and was so taken by him that he contracted to buy all his work for a year [1937-1938] and to subsidize Dali's "Dream of Venus" exhibit for the 1939 New York World's Fair. He was already buying Picassos, and that same year, 1937-38, he patronized Rene Magritte and joined the Surrealist movement in earnest.

"La Reproduction Interdite", the famous Magritte painting of a man shown from behind as he looks into a mirror and sees the same back of head, is a portrait of the back of Edward James' head. He is also the model for the head-as-explosion-of-light portrait Pleasure Principle, though one can hardly tell.

Personally, Surrealism is not my cup of fur. But in James' case the question does comes Up: How does it differ from sheer eccentricity? I think the difference is that Surrealism has purpose. It seeks to shock the viewer into a new way of seeing. Andre Breton wrote, "The marvelous is always beautiful, anything marvelous is beautiful, there is only the marvelous that is beautiful."

James had Tilly's bare footprints woven into the stair carpet at West Dean. He had wooden moldings in the shape of towels hung out beneath the windows of Monkton House, his Surrealist country home. There too stood the original Dali sofa made in the shape of Mae West's lips, in addition to Dali's first lobster-telephone, designed for James, as were the Giacometti andirons. And mock-bamboo drainpipes, wooden palm trees, a boa constrictor lamp, pawmarks of Edward's Irish wolfhound on the stairs, a bathroom with walls of translucent alabaster and a medicine cabinet disguised as a bookcase. Surrealism is about Things. The Surrealism of Edward James, born into a world absolutely cluttered with expensive things and yearning to be free of their magnetism (when periodically overwhelmed by stuff that he accumulated, down to old matchboxes, he would simply have it all wrapped in bushels of tissue, packed in trunks and stored in a warehouse), has a blithe humor tinged with disdain that I sensed often in Las Pozas.

It is impossible to write about the man without dropping names, for one of his great talents was meeting people. It helped to be a rich patron of the arts. While still at Oxford, he founded the James Press for the debut of John Betejeman's poems and his own. Later Betjeman, as British poet laureate, wrote a poem about his friend, "Surrounded by Bells", which appeared in the New Yorker: "The Sun that shines on Edward James / Shines also down on me...."

Names

Edith Sitwell introduced him to Dylan Thomas, whom he sponsored for a while; through Dali he met Sigmund Freud and Steven Zweig; as a regular at Surrealist gatherings he knew Leonora Carrington, Paul Delvaux, Pavel Tchelitchew and others; he sublet a house in Rome to Garbo and Stokowski; he commissioned works by Stravinsky and Poulenc. During World War II he came to America, a visit which took him to Taos, New Mexico, where he met D. H. Lawrence and entourage, including Aldous Huxley. In 1940 Huxley became his ticket to the pantheistic crypto-Hindu Vedanta movement in Hollywood and super chic Ojai, where he met all sorts of people, from Krishnamurti, the great spiritual leader who would not lead, to the major movie stars and directors of the day (including, I note, that other builder of unlived in cities, Cecil B. DeMille) and friends of the great Surrealist filmmaker Luis Bunuel, and on beyond movies to Hollywood's expatriate writers, such as Thomas Mann, Somerset Maugham, Christopher Isherwood and Gerald Heard, and on beyond writers to psychiatrist Erich Fromm.

Then Fromm invited him to spend some time at the American colony in Cuernavaca, Mexico. The country delighted Edward James. It was everything that England wasn't: no censorious social critics, none of that upper-class British inhibition, a concept of time that made this habitual maunderer seem punctual, and best of all, a climate that allowed one to grow plants and animals in lush profusion. For his wealth had become a burden and a source of something close to paranoia : more and more, people were besieging him for money, wheedling and conniving and suggesting worthy projects. One French composer's wife noted in her diary, "Edward James has arrived with his Rolls-Royce, his Duesenberg and, let us hope, his checkbook."

All through his life he doled out money freely to painters and writers, Surrealist or not, even as he built clinics for poor nuns, bought houses in Hollywood and Malibu and land in Mexico, came to the financial rescue of Rodia's Watts Towers and supported platoons of hangers-on. No wonder he preferred animals and plants.

Specifically, it was orchids that first brought him to Xilitla. It was by far the best place to grow them, he was told. He met his friend Plutarco Gastelum, part Yaqui Indian, part Spanish aristocrat and a swashbuckling former rancher, boxer, telegrapher and amateur architect, in a telegraph office in Cuernavaca, where Gastelum, taking James for a poorly dressed tourist complete with cheap silver watch chain, had directed him to the second-class bus stand.

"Oh no, thank you," James replied politely, "I have my car." Whereupon his chauffeur drove up in a Lincoln Continental. In any case, James hired Gastelum as his manager, and later sent him and his wife, Marina, on a tour of Europe.

In 1962 a once-in-a-lifetime frost killed James' orchids by the thousands. Crushed, he decided to recoup in concrete. He would build a city of flowers four stories high that no frost could ever kill. Meanwhile, Gastelum, inspired by Venice and Florence, had started to vastly expand his own house in the village of Xilitla. James came to live there with Plutarco and Marina, their daughters and their lively son Plutarcito, now known to one and all as "Kako." The two great structural follies rose at the same time, influenced by each other.

"I think Uncle Edward was a little jealous of my father," Kako says. "Sometimes he copied ideas he saw here in our house." And no doubt Plutarco imitated his rival too: just inside the gate is a series of stepping stones in the shape of bare feet. The feet are splayed and misshapen like James' own feet, for according to his story he was nearly crippled in childhood by his mother's refusal to buy him big enough shoes.

While James was alive, the Edward James Foundation, which he had set up in 1964 and which ran the West Dean College of art and antiques restoration, supported Las Pozas. But after his death, major support stopped. James had willed the property to Kako and his sisters. At one time, state officials expressed interest in buying Las Pozas and making it a state park. The locals already use the pools freely, as James had urged them to, and patronize a little cafe on the site. But decisions seem far off at the moment. For one thing, all those protruding steel rods will have to be expensively cut off and capped soon or the structures will disintegrate, an unthinkable tragedy in the mind of the young man who calls James "Uncle Edward."

Money to indulge every fancy

Early pictures of James show a slight, trim, neatly handsome man with deepset eyes and a firm chin, but Kako knew him as a bent old Robinson Crusoe, distinctly overweight, with a white beard and a stick, with gnarled feet and the money to do any wild, delightful thing that occurred to him, who lived in this house and talked of the grand, thrilling world outside. James died at 77 of a stroke on a return visit to Europe in 1984.

Las Pozas, Kako, his father and a large cast of characters from James' life figure in the full-length documentary being produced by filmmaker Avery Danziger and his wife, Lenore, who have been working on it so long that they have had time to fall in love with Xilitla and have bought property there. Danziger expects to complete work next month. The film is called Edward James: Builder of Dreams and is destined for public television or a cable channel.

It is remarkable for its priceless record of Las Pozas with James himself guiding the camera about the premises, talking a steady stream-and for the portrait it draws of this engaging, driven man. Friends from all over the world, from actress Ruth Ford to Leonora Carrington to James Bridges, describe James and his life, only to be topped by the master storyteller, James himself, with his deadly ear for accents. He recalls his stately, remote mother who, on her way to church, would ask a servant to send down one of the children from the nursery, ''whichever one will go best with my blue dress."

He tells one interviewer, "I used to have to stay in bed long after the sun had risen, until my nanny got up and dressed me. The sun would rise early, especially in Scotland in August, and I would long to get up and play on the beach. So to amuse myself in bed, aged 6, I would turn the sheets into a great hall and the pillows into towers."

His accent slips easily from hard-edged American to fluty upper-class British. He talks of his animals: the giant butterflies that he named after couturiers Dior, Schiaparelli and Chanel ("the rather dull one in good taste"), the three boas, the parrots, the kinkajous, the ocelots, the ducks and deer and peacocks, the generations of dogs and cats and the four baby crocodiles a friend gave him, one of which "used to sleep in my bed and crawl across and rest his muzzle on my shoulder."

All of James' life, I came to understand, was a search for something to create. His novels never amounted to much, his poems were spangled with good lines but also derivative ones and downright bad ones. It was never enough to support other

artists or even to appear in their work. The animals had to be returned to the wild. The exotic flowers with which he hoped to brighten the world would die all too quickly. It was in Las Pozas that he found at last his true artistic medium.

It was of heroic scale, it covered acres of jungle, it was a world. Its bare reinforcing rods yearned upward as if they would grow still more columns and platforms in the sky, expanding forever.

Yet the strangest thing of all was the apartment that this unworldly accumulator of worldly things, this owner of land in England and America and Mexico, of houses from California to Scotland, built for himself in the leafy heart of his vast fantasy. The apartment has a bedroom, living room and porch on two stories. On one wall is scrawled in pencil his poem "This Shell": "My house grows like the chambered nautilus...."

And it is tiny, a doll's tree house, the smallest possible shell where a man could hide. (You will find Xilitla, Hidalgo on 26 2-C in the Guia Roji Map of Mexico.)