Hi,

Below are two articles about Magritte's 1948 Vache period. I'll give a short summary. The early 1940s was one of the worst times of Magritte's life, not only did the Germans occupy Belgium but his marriage briefly fell apart. In 1943 Magritte trying to overcome a severe depression started painting his sunny impressionistic pieces inspired by Renoir which he calls his sunlit period.

When Magritte live in the suburbs of Paris from 1927-1930 he never received the recognition he felt he deserved. He had no one-man shows and returned to Belgium in bad economic times. By the mid-1940s the French began to appreciate his art and he was invited to do a show in late 1947. In preparation for the show, during a five week period in 1948, he decided to paint some joking impressionist paintings to exert some revenge on the French for snubbing him for so long.

Magritte called these paintings jokingly his “vache” paintings which in french does not only mean “cow,” but also as much as “mean” or “dirty”; “vacherie” signifies a dirty trick.

Here are two articles about the 1948 Vache period:

Bernard Marcadé on René Magritte: Bernard Marcadé is a critic and freelance curator based in Paris. His Marcel Duchamp biography was published this year by Flammarion.

In 1947 Magritte gave up what he called his "tactile conformism" partly to distance himself from the rigours of Parisian Surrealism. He painted a series of hilarious pictures that trumped his colleagues- until his wife Georgette complained. Bernard Marcadé looks at René Magritte's Période Vache.

Art history likes periods, whether for the purposes of simplification or edification. Thus Picasso’s blue and pink periods are evoked, most often in order to contrast them with one another, as are Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical and return-to-order periods, or the mechanomorphic and abstract periods of Francis Picabia. In most cases the artists themselves play no part in these classifications and registrations. They are particularly difficult to determine when René Magritte is concerned. It is possible, of course, to perceive Impressionist and Cubist influences at the beginning of his career. But running contrary to the abstract, figurative, automatic and oneiric styles that ceaselessly articulated the history of painting at this time, and Surrealism in particular, Magritte would opt, from 1925 onwards, to “paint objects only with their apparent details”.

So it was with full knowledge of the facts that he twice decided to break with the “tactical conformism” that he had until then freely imposed upon himself: in 1942 with the period referred to as “Impressionist” or “Renoir”; and in 1947 with his “vache” – literally cow – period. It’s hard to understand these decisions outside of their historical context, that of the Second World War and the Liberation. The painter’s Impressionist period also coincides with his self-distancing from official Parisian Surrealism. His manifesto Surrealism in full sunlight, which he concocted in 1946 with the complicity of Marcel Mariën, Paul Nougé, Louis Scutenaire, Joë Bousquet, Jacques Michel and Jacques Wergifosse, a prelude to the manifestoes of extramentalism and amentalism, is an instrument of warfare directed against the magic, esoteric ideology into which André Breton had strayed. “We have neither the time nor the taste to play at Surrealist art, we have a huge task ahead of us, we must imagine charming objects which will awaken what is left within us of the instinct to pleasure.”

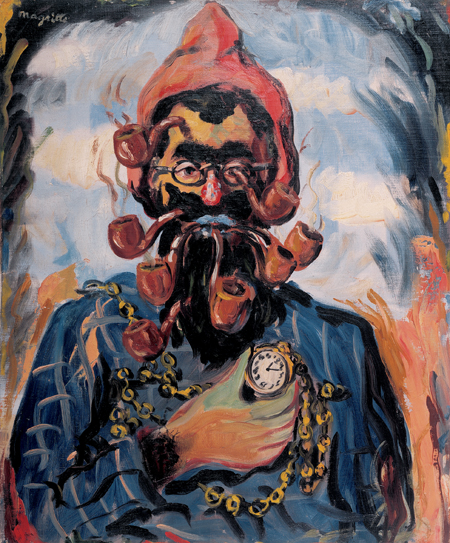

It was in this polemical context that Magritte was invited to hold his first solo exhibition in Paris at the Galerie du Faubourg in May 1948. For the occasion, over five weeks he made the seventeen oil paintings and twenty or so gouaches which, taken together, he would then call his vache period. Behind this term, of course, we must read an ironic reference to the historically listed Fauve (literally wild beast) painting of Derain, Matisse and Braque. Vache would thus be the conniving and trivial reverse of Fauve, a term that was originally pejorative but which has, over time, been wreathed with the values of lyricism and flamboyance. The category of bovidae in fact supplies fewer inspiring metaphors than that of wild beasts. In French, the term vache is used for an excessively fat woman, or a soft, lazy person. An unpleasant person is described as a peau de vache (cow-skin); amour vache (cow-love) refers to a relationship more physical than emotional. It thus treads a line between vulgarity and coarseness, and that is what characterises this set of paintings and gouaches, representing a radical departure from the painter’s neutral, detached style which had finally been accepted by Parisian Surrealist orthodoxy. Overall, the striking thing about these works is their garish tones, their exuberant, grotesque and caricatured subjects, all executed rapidly and casually in the name of a freedom from aesthetic and moral injunctions and prescriptions.

The exhibition was accompanied by a small catalogue with a preface by the poet Louis Scutenaire, bearing an evocative title (“ Les pieds dans le plat” – Putting one’s foot in it) and written in a slangy style, which is clearly in line with Magritte’s intentions. Moreover, Scutenaire would admit as much some years later: “The important thing was not to enchant the Parisians, but outrage them.” The triviality of the works actually wrong-foots Surrealist good taste. Both text and images are placed on a deliberately rustic and provincial register. “We’d been fed-up for a good long time, we had, deep in our forests, in our green pastures.” Traditionally, the Belgians are seen as coarse peasants by the French, including the intellectuals (in about 1865 Charles Baudelaire had written his pamphlet Poor Belguim). This chauvinism, still prevalent event among the holiest of holies of Parisian Surrealism, is here in a sense returned to sender, “We’d like to say shit politely to you, in your false language,” Scutenaire goes on to write. “Because we bumpkins, we yokels, have absolutely no manners, you realise.”

The tone is set. Scut’ and Mag’ (their signatures, indicating their friendship and complicity) have decided to turn this exhibition into a kind of explosive manifesto against the arrogance and pedantry of the sycophants of the ideology advocated by André Breton. “The moment had come to strike a great blow,” Scutenaire would explain in retrospect. The two associates laid it on the line, The works shown in Paris joyfully mix comedy, viciousness and coarseness of the most scatological kind. In this respect they continue the visual counterpart to the three tracts that Magritte published in 1946 along with Marcel Mariën ( The Imbecile, The Pain in the Arse, The Sod), in which one could already read a supreme contempt for all kinds of convention. Pictorial Content is probably the painting in the series which best allegorises Magritte’s desire to attack the pictorial practices with which he himself had engaged up until that point. It is no longer resemblance that is brought to the fore here, but an excess of distortion and a stridency of colour.

The runny trickles provide a kind of sabotage of the idea of painting which to a certain extent anticipates what would be, some 30 years later, at the heart of the so-called Bad Painting which, from German Neo-Expressionism to the Italian trans-avantgarde, via French free figuration, erupted across the world of Western art in the late 1970s and 1980s. In it, in fact, we find a similar way of integrating the devalued registers of popular culture (advertising, comic strips, graffiti). Scutenaire suggests that this series of paintings was to a large extent inspired by “caricatures shown by Colinet, published before 1914 in magazines for children”. It is true that one can recognise, here and there, explicit references to certain caricatures by the Belgian cartoonist Deladoës, or even direct borrowings of scenes from the Adventures des Pieds nickels, the famous strip drawn by Louis Forton for L’Epatant (The Mountain-dweller, Pictorial Content, The Triumpal March, Jean-Marie, Famine).

In spite of their unbridled style, they are not entirely alien to the painter’s universe. The Ellipse, depicting a huntsman whose rifle appears where his nose should be, The Old Soldier (a poor, ill, veteran who can no longer fight, decked out with five pipes and three noses), an eagle’s head topped by a fortress ( Prince Charming) participate in René Magritte’s visual rhetoric. But that rhetoric is subjected to such chromatic stridencies, to such formal anarchy, that the pleasure principle is plainly the determining factor here. In the end, these insolent works have less in common with de Chirico or Picabia, who were, at the same time, radically transforming their style by miming “traditionalist” attitudes, than they do with an approach such as that of Martin Kippenberger between 1980 and 1990, undermining from within the dominant forms of the art of his time.

The exhibition at the Galerie du Faubourg enjoyed no commercial success. But the target had been hit. The Parisian Surrealists felt they were being aimed at, and were duly offended. This période vache could not subsequently be transformed into a style. Barely a few weeks after the opening of the show, Magritte used the excuse of his wife’s supposedly negative reaction to bring the adventure to an end. “I would quite like to continue with the ‘approach’ I experimented with in Paris, and take it further. That’s my tendency: one of slow suicide. But there’s Georgette and my familiar disgust with being ‘sincere’. Georgette prefers the well-made painting of ‘yesteryear’, so particularly to please Georgette in future I’m going to show the painting of yesteryear. I’ll find a way to slip in a great big incongruity from time to time.”

LA PÉRIODE VACHE- RENÉ MAGRITTE 1948

30 October 2008 – 4 January 2009

René Magritte numbers not only among the most important, but also among the most popular twentieth-century artists. Often against the grain of the artistic tendencies of his time, the Belgian Surrealist painter developed a unique and unmistakable pictorial language. His work’s continuing crucial influence on later generations of artists and his impact on today’s visual culture are almost without par. Many of his enigmatic and equally hard-to-forget solutions have been reproduced in the millions and become famous icons far beyond the world of art.

However, a fascinating period of the artist’s landmark oeuvre has remained nearly unknown: his so-called Période vache. In 1948, Magritte made a group of paintings and gouaches distinctly different from the rest of his work for his first solo exhibition in Paris. Relying on a new, fast and aggressive style of painting – and particularly inspired by popular sources such as caricatures and comics, but also interspersing his works with stylistic quotations from artists like James Ensor or Henri Matisse – Magritte, within only a few weeks, produced about thirty entirely uncharacteristic works that caused an outrage in Paris. The artist deliberately conceived the exhibition as a provocation of and an assault on the Parisian public. Painting in an unexpectedly crude, playful, and intentionally “bad” manner, he reflected his own work and painting in general. While only sporadically included in most retrospectives of Magritte’s oeuvre, his works from the Période vache will be assembled in the exhibition at the Schirn outside France and Belgium for the first time. Especially against the background of the last thirty years’ art, this concentrated presentation will shed new, surprising light on an extraordinary artist whose work is often mistakenly regarded as far too familiar and easy to grasp.

The fact that Magritte’s first solo presentation in Paris did not take place before 1948 is of crucial relevance for the genesis of his Période vache. Paris was not only the center of the art world, but also the capital of the Surrealist movement, and Magritte, as the central figure of Belgian Surrealism, had been in close contact with the circle around André Breton since the 1920s. Yet, it was not only his attempt to establish himself in the French metropolis that failed after only a three-year stay (1927–1930); even after his international recognition had grown in the 1930s, he was denied an adequate appreciation of his work in Paris.

In addition, Magritte came into direct conflict with Paris after the war when his redefinition of Surrealism met with the disapproval of the Surrealist group’s protagonists returning home from exile. In the preceding years, which Magritte had spent in Brussels under German occupation, he had made a programmatic turn and thus laid the foundations for the period of his work known as la Période Renoir or la Période soleil today: falling back on the French Impressionists’ colorful style, he propagated a change of direction towards “the beautiful side of life” and, dissociating himself from the official Paris line, launched a “Surrealism in the blazing sun” (surréalisme en plein soleil). He vehemently attacked the reactionary attitude of an avant-garde movement that he regarded as ossified and tried to convince Breton of his intentions. In vain – not only the manifestos he initiated but also his works in the Neo-Impressionist manner met with general rejection and criticism.

This was the polemical context in which Magritte regarded his invitation to Paris in 1948 less as an overdue chance of success in the French metropolis but rather as an opportunity for taking revenge – for the arrogance of the capital’s art scene and the ossified attitude of a Surrealism that had outlived itself and become far too socially acceptable – by pulling off a surprising coup.

The term “vache” used by Magritte for his new group of works is mostly understood as an ironical allusion to the historical movement of the Fauves, whose exaggerated coloring Magritte’s works parodied as much as their decoratively pleasing character. Yet in French, “vache” does not only mean “cow,” but also as much as “mean” or “nasty”; “vacherie” signifies a mean trick. Other related words are “femme vache” for an extremely corpulent woman, “peau de vache” for a horrible, malicious person, or “amour vache” for brutal carnal love. Thus, the term hints at the aggressive and deliberately crude quality characteristic of the pictures.

Regarding both their motifs and their style, the works of Magritte’s Période vache do not constitute a consistent ensemble but rather present themselves as a patchwork of different pseudo-styles borrowing more or less openly from other artists and drawing on the artist’s own earlier works. These elements are transformed into something comic, trivial, or grotesque by being blended with aspects of popular visual culture. With numerous art historical references – like to James Ensor, whose grotesque physiognomies are given another turn of the screw, to Henri Matisse, whose colorful ornaments are degraded to wallpaper-like décor, or to Joan Miró, who, as we know, was not held in high regard by the artist – Magritte ridicules traditional cultural values and aesthetic norms and distances himself from an art scene lusting for innovation. By presenting motifs taken from his own previous pictures in a new manner of painting, he turned into his own caricaturist, as it were. Contrary to his “classical” works, their cool, precise and realistic approach, and the conceptual consideration behind them, the works of Magritte’s Période vache strike us as colorful, two-dimensional, quickly painted, and radiating an astounding directness and spontaneity.

The exhibition in Paris turned out the expected failure. Not one picture was sold. The press reacted frostily. The public was appalled. The Paris Surrealists kept their distance. Only one of the vache works was exhibited again during Magritte’s lifetime, i.e. until 1967. For exhibition makers as well as art dealers and art historians, this group of works constituted an alien element in an otherwise extraordinarily consistent oeuvre. In addition, it did not fit

in with the image of an artist who had, above all, been presented as a pioneer of Pop art and Concept art since the 1960s. It was not before thirty years after their making that these hitherto forgotten works began to be gradually reevaluated and appreciated starting with the “Westkunst” exhibition in Cologne.

In the context of the 1980s’ Post-Conceptual painting, the strategies Magritte had relied on for subverting the prevailing standards of painting in the medium itself appeared both exemplary and highly topical. Today, about forty years after Magritte’s death, contemporary artists such as John Currin or Sean Landers often come to understand his oeuvre by making themselves familiar with the works of his Période vache at first. The works’ humor, spontaneous style, and daring bad taste provide an example for a form of painting deriving its momentum from the apparent meaningless of its subjects in order to refute the clichés of today’s world of images. With his manifesto-like protest against all varieties of arrogance and reprimands in the arts, Magritte has become a model for the artist’s triumph over the workings of an art scene that seem to be more overpowering today than they ever were.

With “René Magritte 1948. La Période vache,” the Schirn continues a series of exhibitions that started with “Henri Matisse. Drawing with Scissors” and “Paul Klee. 1933” and was followed by “Max Beckmann. The Watercolors and Pastels” or “Picasso and the Theater,” focusing on extraordinary groups of works or scarcely noticed aspects in the oeuvre of established masters of classical modernism.

CATALOGUE: “René Magritte 1948. La Période vache.” Edited by Esther Schlicht and Max Hollein. With a preface by Max Hollein and texts by Michel Draguet, Robert Fleck, Florence Hespel, and Esther Schlicht. German and English, 176 pages, ca. 90 illustrations, Ludion, ISBN 978-90-5544-768-8, 29,80 € (Schirn), ca. 34,90 € (Ludion).