Hi,

On June 17, 2007 Rene Magritte's 1959 "Le Sabbat,'' featuring an upside-down easel in a landscape, took 4.5 million pounds from a European bidding on the phone. It was once owned by Monaco-based dealer and collector David Nahmad, who said he sold it in 1975 for $100,000.

One of my paintings, Reflections, (see: New Paintings- above right) is a painting on an eisel upside down- there's even a guy with an umbrella! Maybe there's hope for my paintings yet- lol. There are several paintings in my Driftwood Series that can be turned upside down, viewed either way!

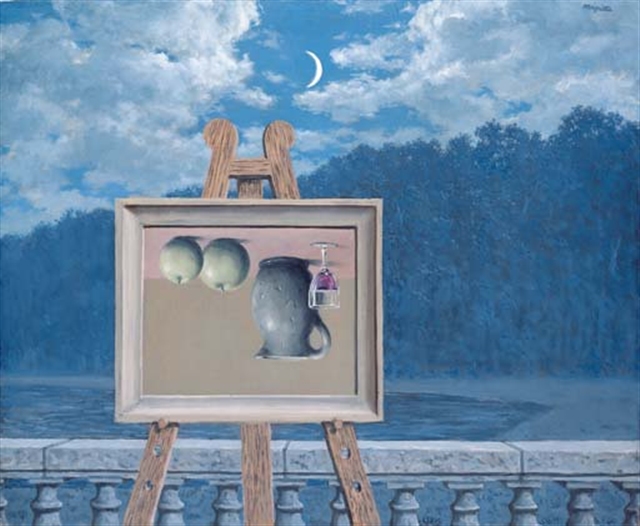

Le sabbat

Title: Le sabbat by René Magritte

Description: Le sabbat signed 'Magritte' (upper right); titled '"Le Sabbat"' (on the reverse) oil on canvas 19¾ x 24 in. (50 x 61 cm.) Painted in February 1959

Provenance:

Alexander Iolas, New York, by whom acquired from the artist (no. 59.1.1; despatched by the artist to Paris in February 1960).

Patrick O'Higgins, New York, by whom acquired from the above.

Mayor Gallery, London (no. 5040).

Anonymous sale, Sotheby's, London, 2 December 1970, lot 57.

Galleria Medea, Milan.

Private collection, by whom acquired from the above.

Galleria La Bussola, Turin, by 1986 (no. 8A313).

Private collection, Italy.

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

Exhibited:

Charleroi, Palais des Beaux-Arts, XXXIIIe Salon [du] cercle royal artistique et littéraire de Charleroi, March 1959, no. 120.

Brussels, Musée d'Ixelles, Magritte, April - May 1959, no. 102.

Paris, Galerie Rive Droite, René Magritte, February - March 1960, no. 3.

Little Rock, Arkansas Art Center, Magritte, May - June 1964.

Notes:

A painting sits on an easel, a landscape beyond it. And yet the two have little in common: the night-draped landscape that spreads before us has, it is implied, been represented in the picture-within-a-picture by a still life. And it is upside down. In Le sabbat, painted in 1959, Magritte has turned his strange and surreal gaze towards perception and painting itself. This most natural of themes for someone who had chosen art as a vocation is here exposed in all its splendour and mystery.

Ever since Zeuxis painted an image of fruit that managed to confuse birds to the extent that they tried to peck at his image, the concept of art has been a source of reflection and interest to artists. Sometimes this is a result of their own awe at the act of representation, the mini-creation with which each art object is dragged into existence. This mystery is potent enough that the act of representing the world figuratively has been proscribed in some religions. But when it came to Magritte, an artist known for revealing the mystery that is apparent in the everyday objects of the everyday world, it is intriguing to note that one of his first works that tackled the subject of representation itself was La trahison des images. In this, Magritte acted as the anti-Zeuxis by representing a pipe on canvas, and painting under it the now-famous words, 'Ceci n'est pas une pipe'.

By creating that juxtaposition between words and text, by stating the obvious and declaring that an image is not an equivalent for the object that it represents, Magritte appeared to be removing the mystery. And yet... there was in fact more mystery invoked, as Magritte was pointing to the strange reactions that are reflexes in the viewer, to the bizarre and almost magical process through which usually we do believe that a picture of a pipe represents a pipe. In Le sabbat, Magritte evokes the mystery of representation in a different way, by showing a picture on an easel that is both impossible-- in its being upside-down-- and wholly incongruous, because of its apparent lack of relationship with the scenery behind it. There is no room even for a game of disjointed association. There are no links. This is a realm of magic, and it is through this jarring magic that the viewer perceives all the more the mystery of painting. For it is the painting on the easel that is the main theme, the main motif, in Le sabbat.

This theme had been explored two years earlier in a pair of works both entitled Le réveille-matin, or 'The Alarm Clock'. In these works, an upside-down still life is shown upon an easel before a sprawling day landscape. In Le sabbat, the moonlit night heightens the mystery. And the fact that the picture within Le sabbat is smaller than in those works emphasises the landscape behind, ensuring that the viewer's attention is focussed on the seemingly discordant relationship between what has been seen and what has been painted. The painting is only truly 'revealed' by Magritte through its association, or lack thereof, to the landscape. And in this, the artist manages to illustrate the strangeness of perception itself. It is not the act of painting alone whose strange pitfalls and bizarre, even illogical, mechanics are exposed, but also the very act of seeing. And this seeing is focussed upon both in terms of looking at a landscape (and seeing a still life?), and in terms of looking at paintings, looking at art. Should this picture hang in a gallery filled with 'normal' still life and landscape images, would it not pull the rug from under those paintings' figurative feet?

Adding an extra layer of the mysterious to Le sabbat and heightening this sense that perception itself should not be taken for granted and should not be so rigid as we all to often allow it to become, Magritte has not only inverted the still life image, but has also included within it a vase that appears to be made of stone, lending it a monumentality that itself adds to the visual drama of the gravity-defying ceiling-hugging still life. Despite this, there is nothing strictly impossible within Le sabbat-- yet an atmosphere of the unreal nevertheless pervades the work. And this atmosphere is increased by the fact that Magritte himself, in painting Le sabbat, has painted something that clearly was not before him in any literal sense. He has, instead, tapped into his own unique vision in order to bring through the discreet poetry that exists in our everyday lives and to which we are all too often oblivious. It is for this reason that he shunned so many of the terms that were applied so freely to his painting not least 'Surreal'. 'I must inform you however that words such as unreal, unreality, imaginary, seem unsuited to a discussion of my painting,' he explained.

'I am not in the least curious about the 'imaginary,' nor about the 'unreal'. For me, it's not a matter of painting 'reality' as though it were readily accessible to me and to others, but of depicting the most ordinary reality in such a way that this immediate reality loses its tame or terrifying character and finally presents itself with its mystery. Understood in this way, that reality has nothing 'unreal' or 'imaginary' about it' (Magritte, quoted in H. Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, trans. R. Miller, New York, 1977, p. 70).

Magritte's pictures, then, are revelations, little epiphanies that still reverberate with that initial moment of lucidity that the artist himself had felt when seeing Giorgio de Chirico's Le chant d'amour in reproduction for the first time. That sudden awareness of the almost alchemical poetry that somehow exists in our world-- just beyond the layer that our eyes see-- is forcefully brought to our attention in the deliberately discordant lyricism of Le sabbat.