Magritte and Poe: Strange Brew

by Richard Matteson (from various sources)

Edgar Allen Poe was one of Magritte's idols. In "The Other Wordly Landscapes of E.A. Poe and Rene Magritte" Renee Riese Hubert pointed out:

"Several critics have found most intriguing Rene Magritte's outspoken admiration for Edgar Allan Poe. Hammacher recounts that the painter, during his only trip to the U.S. absolutely insisted on a visit to the Poe shrine."

Below are two of Magritte's masterpieces that are directly related to Poe and some information from me and other sources:

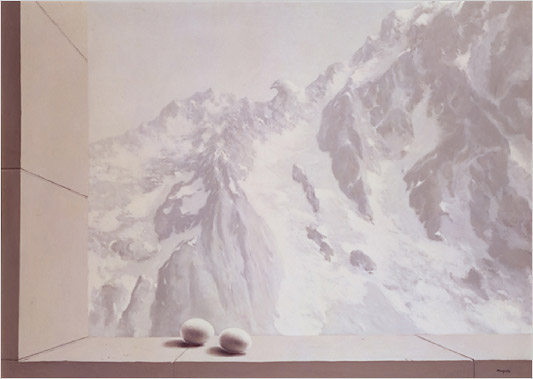

Domain of Arnheim 1938 oil on canvas (first oil version) Arnheim translates loosely from the German as eagle’s nest.

In 1938 Magritte painted a gouche and an oil of his Domain of Arnheim based on Edgar Allen Poe's story “The Domain of Arnheim:”

[From Poe:] "…no such combination of scenery exists in nature as the painter of genius may produce. No such paradises are to be found in reality as have glowed on the canvas of Claude. In the most enchanting of natural landscapes there will always be found a defect or an excess — many excesses and defects. While the component parts may defy, individually, the highest skill of the artist, the arrangement of these parts will always be susceptible of improvement. In short, no position can be attained on the wide surface of the natural earth, from which an artistical eye, looking steadily, will not find matter of offence in what is termed the ‘composition’ of the landscape. And yet how unintelligible is this! In all other matters we are justly instructed to regard nature as supreme. With her details we shrink from competition. Who shall presume to imitate the colours of the tulip, or to improve the proportions of the lily of the valley?"

The Domain of Arnheim may be Poe's greatest story. Poe himself held it in high esteem. He wrote, “ ‘The Domain of Arnheim’ expresses much of my soul.”

To Magritte The Domain of Arnheim represented the ideal landscape as expressed by Poe. Magritte also used the granite eagle on the mountain ridge in others works with different titles. The image of the mountain shaped like an eagle predates the “Domain of Arnheim” images, appearing in “Le precurseur” (1936) and other 1933-34 works. In fact the earliest mountain/eagle image is found in the 1926 "The Wreckage of the Shadow." The catalogue raisonné says, “The mountain may well have been based upon the upper two-thirds of a color reproduction of a photograph found among Magritte’s papers, something he certainly handled, as it bears a drawing by him on the verso.”

The “Domain of Arnheim” series:

1938 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 30 x 38 - whereabouts unknown

1938 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, oil on canvas

1944 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 33 x 46 - Caroline Pigozzi

1947 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 37.1 x 46.2 - Private collection, U.K.

1948 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 34 x 36 - Private collection

1949 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, oil on canvas 100 x 81 - Private Collection

1962 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, oil on canvas 146 x 114 - Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

1962 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 35 x 27 - Private Collection

1962 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper, 25 x 19.2 - Eleanor Cramer Hodes

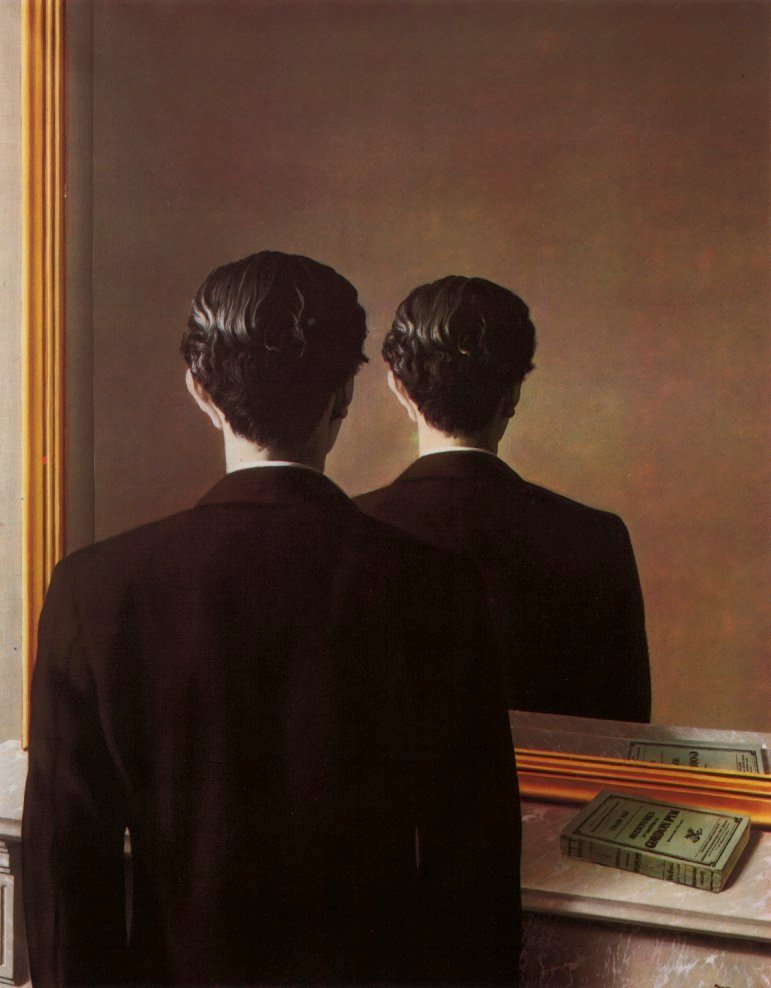

Réné Magritte, La reproduction interdite, 1937, oil on canvas, 81.3 x 65 cm (©Museum Boymans-van Beuningen).

In his Surrealist Manifesto published in 1924, poet and critic André Breton, making extensive use of theories adapted from Sigmund Freud, proposed that the conscious and unconscious artistic impulses be reunited under the artistic banner he termed “surrealism”:

I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak.

Breton advocated banishing reason from the realm of artistic creation, arguing that a reliance on “automatism” (unconscious, spontaneous behavior) would call forth more authentic images from the dream and supernatural states.

For his masterful La reproduction interdite (Not to be reproduced) Réné Magritte has created a representation of his subject—Edward James, a rich English aristocrat, Surrealist poet, and patron of both Dali and Magritte—that is both rigorously realistic and emotionally detached. A master at posing familiar objects in absurd contexts, Magritte made extensive use of mirror and glass in his work, playing with their ability to hide or mask through reflection. In this painting Magritte presents us with the view of his subject seen from behind. The reflection in the mirror beyond, however, violates the laws of nature, for it reflects that very same backside view back to us. We gaze over the man’s shoulder expecting to see his face (i.e. his specific identity) and are met instead with the view from our own eyes. The subject’s identity is hidden from us. In the world Magritte has created here we can only ever return to ourselves (i.e. our own reality).

To confuse us further, Magritte has placed Edgar Allan Poe’s book The Narrative of Arthur Golden Pym next to James on the mantel, juxtaposing its “correct” reflection with the alternative reality of the figure’s reflection. Magritte has created a painting with dual realities, alternate fictions, if you like. The book itself provides a small clue as to Magritte’s intentions.

Magritte was an unabashed admirer of Poe. In particular, he was inspired by the writer’s preoccupation with the mingling of the real and artificial. The Narrative of Arthur Golden Pym, Poe’s only novel, purports to be a non-fictional tale of the fantastic sea journey of Arthur Pym from Nantucket to the land of Symzonia (somewhere in the South Pacific?). Along the way, the narrative proves to be distorted and unreliable, deceitful even. The various twists of the novel’s plot embody numerous thematic elements, but masquerade, illusion, and even trickery figure prominently in the action. Ultimately, the tale reveals itself as a figment of the protagonist’s imagination—a fiction cloaking a fiction.

Claudia Kay Silverman (American Studies, UVA) further observes—

The journey enacted in Symzonia, the journey to the interior of the earth, can be construed as a journey of anti-discovery. It is a journey to discover an emptiness. As does all Utopian fiction, the journey of Symzonia contains a tension. A Utopia is both a “good place” and “no place;” the journey to the interior of the earth is the ultimate journey and the impossible journey. It finds, in those imaginatively inclined, a correlative in a journey into the mind itself, whose outcome will be the unveiling of the deepest secret of humanity.

The grip that the notion of a hollow earth might have had on Poe has to do with a fear that the human mind, rather than containing ultimate knowledge, is, at its very core, empty.

The themes of search and deceit, which weave in and out of Pym’s tale, must have appealed greatly to Magritte’s well-developed epigrammatic sensibility. La reproduction interdite is a witty commentary on our search for identity. Human beings, to paraphrase Magritte, always want to see what lies behind what they can actually see. We seek to uncover an essential or unconcealed “reality” or “truth,” which in turn will define who we are. Alas, the painter is in charge of this world; he makes that clear by doing exactly what the title forbids, i.e. copying.

La reproduction interdite proffers a world in which we can only view the reality that we already see. The painting seems to be saying that an individual’s own vision is the reality that matters. As Jung said, “it all depends on how we look at things, and not how they are in themselves.”

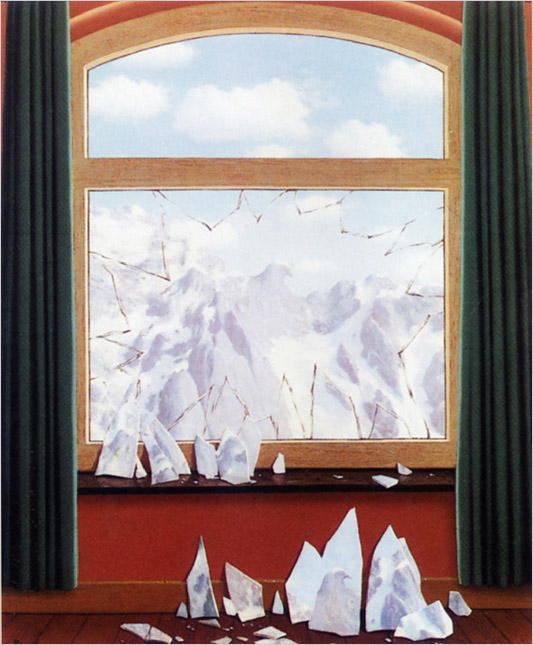

From "The Poker-Faced Enchanter" by Robert Hughes - Time Magazine [refers to Version 2- above]

"Then there was Edgar Allan Poe. Magritte used him repeatedly. The Domain of Arnheim, Magritte's image of a vast, cold Alpine wall seen through the broken window of a bourgeois living room, with shards of glass on the floor that still carry bits of the sublime view on them, is the title of Poe's 1846 tale about a superrich American landscape connoisseur who creates a Xanadu for himself. 'Let us imagine,' says Poe's hero, 'a landscape whose combined vastness and definitiveness -- whose united beauty, magnificence and strangeness shall convey the idea of care, or culture . . . on the part of beings superior, yet akin to humanity . . .' Yes, one can well imagine Magritte liking that. His work too sets up a parallel world, extremely strange and yet familiar, ruled by an absolutist imagination."

From History of Art:

It is not only to Stevenson that Magritte makes reference in his pictures. Mention should be made of Hegel as regards In Praise of Dialectics, Baudelaire in connection with Flowers of Evil and The Giantess, as well as Verlaine, Heidegger and Lautreamont. More than any other writer or philosopher cited here, however, it was without doubt Edgar Allan Рое who exercised the most powerful and lasting influence upon Magritte's thinking and on his work as a whole.

Take, for example, the well-known story "The Purloined Letter". A minister who enjoys the confidence of the royal couple observes the Queen trying - successfully - to conceal a letter from her august spouse. Before the Queen's eyes, the minister steals the letter, substituting another for it. The Queen has no choice but to remain silent; any protest at the theft would inevitably bring with it the disclosure of the very piece of evidence which she is seeking to keep secret. In order to extricate herself from this dependence, the Queen instructs the Prefect of Police to recover the stolen letter, taking care to describe to him the seal of red wax with which it was closed. The poor official sets to work, blindly and without further thought, yet all his investigations come to naught. In contrast, Dupin, whom he has told of his misfortune, strikes it lucky, immediately espying the letter in the minister's cabinet. On a second visit to the cabinet, he sees no more than the reverse of the letter, crumpled and closed with a black seal. He nevertheless manages to recover it by means of a clever tactic: he arranges for a shot to be fired outside in the street, and when the minister opens the window to see what has happened, the cunning Dupin seizes the letter, conjurer-like, substituting another letter for it, in which is written -in Dupin's own handwriting, with which the minister is familiar -some lines by Crebillon the Older: "... such a sinister plan, if unworthy of Atreus, is worthy of Thyestes."

The letter, the written word, which has been stolen here, alters its meaning upon changing owner, since the new owner, the communication falling into his possession, himself becomes one possessed. What in the Queen's hands is a declaration of love proving her infidelity becomes in those of the minister a means of blackmail, albeit one which turns out to be unusable, since it calls into question the very unity between King and Queen from which he, the minister, draws his entire power. The letter in his hand simultaneously provides evidence of the disorder which it is his job to prevent; he cannot restore order without doing himself harm. Dupin, in stealing back the letter, reveals the conceited, narcissistic superiority of the minister to be no more than illusion: all that is lacking is that the latter, following the example of Thyestes, should devour his own children. Dupin sells the letter to the Prefect of Police, who, for his part has seen nothing and understood less. The Prefect's mistake lay in searching for the real letter, rather than for its sense, which is modified every time the letter changes owners or external appearance. This story by Edgar Allan Рое, in which the actors are divided into observers of action and observers of reflection, reads like an introduction to the art of Magritte. It is not sufficient, upon looking at his pictures, to study what can be seen, to check identities; rather, it is necessary to reflect upon what one sees, to imagine it.

It is only through such a meditative attitude that the observer can gain access to Magritte's subtle game of enigmas. This does not mean, however, that it is possible to grasp this mystery as one would a possession. Reflection merely enables one to sense the mystery; it does not offer any concept, any formula, any key. Patrick Waldberg has rightly remarked that one could speak here of a "key of ashes", one which opens up nothing and fits no lock. The thoughts which become visible in Magritte's pictures lock up their secret as soon as the observer believes that he has completely plumbed the depths of their meaning. The images are poetic through and through.

The Domain of Arnheim, a principal work which exists in different versions on canvas and in gouache, emphasizes in another way the unreserved admiration which Magritte evinced for Edgar Allan Рое. The artist borrowed the title from Рое, depicting a mountain with the form of an eagle, while two bird's eggs in the foreground refer to the lightness of poetry, to the affinity of the latter's nature to that of air. In so doing, he was establishing a lasting monument to his greatest source of inspiration.