Selling Le Domaine Enchante

by Andrew Decker

%201953.jpg)

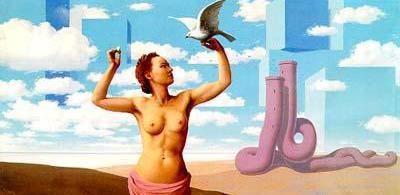

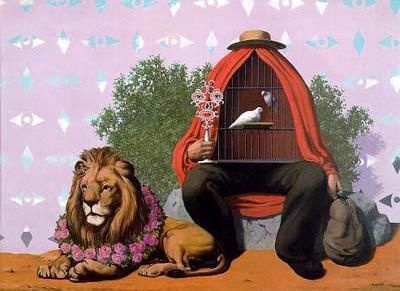

Le Domaine Enchanté (I)

1953

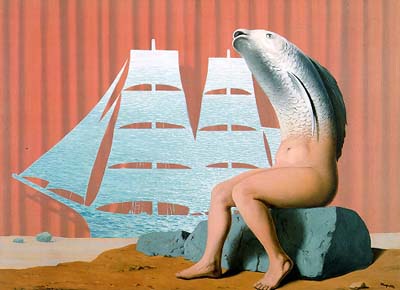

Le Domaine Enchanté (II)

1953

%201953.jpg)

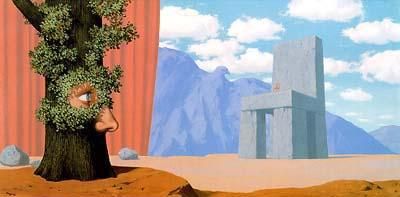

Le Domaine Enchanté (III)

1953

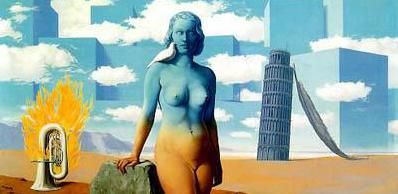

Le Domaine Enchanté (IV)

1953

Le Domaine Enchanté (V)

1953

Le Domaine Enchanté (VI)

1953

Le Domaine Enchanté (VII)

1953

Le Domaine Enchanté (VIII) 1953

On July 1, René Magritte's eight-painting series from 1953, Le domaine enchante, goes up for sale at Christie's London. Together measuring more than 32 feet (six canvases at approximately 27 x 54 in. and two at 27 x 37 in.), the series is a mini-retrospective of Magritte's Surrealism, combining into one neat grouping a slew of the artist's signature images -- pigeons transmogrifying into foliage, masked apples, houses lit at dusk against a backdrop of a daytime sky, an inverted mermaid or fishwoman.

Unfortunately, Christie's has decided to break up the series and sell the paintings individually, presumably to maximize the price. Presale estimates for each picture range from a low of $600,000-$800,000 to a high of $1.8 million-$2.5 million.

Of course, there's no law against dismantling a series, and Christie's made its decision after the sly (and anonymous) consignor played the house off against its arch-rival, Sotheby's. And from the seller's point of view, the timing couldn't be better.

Especially now. Christie's (like Sotheby's) has had a dry season as far as modern paintings go, and the eight domaine paintings carry a low estimate of $11 million -- about a third of the total value of the Christie's July 1 auction. Christie's was keen to get the series, with property in short supply and a market heading toward the boiling point.

How hot is the market? Look at the last month's results. Just think of Christie's brilliant success with the heavily hyped Herbig collection, and the punishing bidding for Warhol's Orange Marilyn at Sotheby's in May, when the painting soared to $17,327,500. Several insiders assumed the buyer was Condé Nast head S.I. Newhouse, Jr., simply based on his relentless, no-pause bidding style. Referring to the billionaire's 1988 purchase of Jasper Johns's False Start for $17.05 million, beating out as underbidder the neophyte and later bankrupt collector Hans Thulin, the insider said, "It was False Start all over again."

Is it the '80s all over again? Simply, the answer is no, but with an asterisk. Yes, art is hot in the shelter magazines, with House & Garden devoting its May issue to the theme of "Living with Art." But art isn't popping up on the sets of movies now as a Julian Schnabel plate picture did in the "greed is good" masterpiece, Wall Street. Fashionable yes, mass-media, no.

But things appear to be heading that way. Signs of a boom verging on a craze are all over the place. Contemporary artists at the beginning of their careers, like Sharon Lockhart and Elizabeth Peyton, and the mid-career Luc Tuymans have waiting lists. During the last year, Charles Saatchi has again become a barometer of which artists to buy, just like he was in the '80s. (His purchases have included works by Amy Adler, who shows in New York at Casey Kaplan, and Juan Usle, who shows at Cheim & Read.)

The current upturn is perfectly predictable. For the past 50 years, the art market has run in a seven to nine year cycle. A two or three year trough is followed by a period of normalcy, marked by little inflation -- a largely sane period where collectors pick and choose and most everything has a reasonable value. Then comes a spike of madness fueled by some random factor involving money -- inflation, a "bubble economy" or some other factor driving the global finance.

The people behind these art booms tend to share a few characteristics: no particular knowledge about art, access to a lot of money, and the ability to be mesmerized and intrigued by a spectacular link between art and money -- a $17 million Warhol, for instance.

A new buzz among art professionals involves lending against art. One New York dealer, who is occasionally given to hyperbole, says, "Yesterday I was playing golf with a bunch of bankers, and they're all interested in lending money against art. What they're looking for is expertise in this area. Bankers see art collections and see money sitting in pictures and think it's just dead capital." The way to enliven the art -- obviously, studying it, looking at it and enjoying it couldn't possibly be enough -- is to borrow against it. Then there's money to sink into some other investment, possibly including more art.

If using your art collection as collateral is a hot topic, there's also the old tried and true practice of "flipping" -- that is, buying on speculation in one arena and trying to sell for a profit in another. Le domaine enchanté is an example of both lending gone bad and a '90s flip.

During the '80s, domaine was owed by Belgian collector and Magritte enthusiast Isy Brachot, who sold it to the Fuji TV Gallery in Tokyo for an undisclosed price that was probably close to $15 million. Fuji then sold it to Tomonori Tsurumaki, the Japanese businessman also known for paying $51.65 million for Pablo Picasso's Les Noces de Pierrette in 1989. Turumaki was one of those late '80s collectors who had too much of other people's money to throw around. Aside from buying the Magritte and the Picasso, he sank hundreds of millions into a car racetrack, the Nippon Autopolis.

Then, after the collapse of the market, it wound up as the property the Lake Finance Company, a Tokyo lending institution that had provided Tsurumaki with so much of his borrowed millions. Lake floated it on the market in the mid-'90s, hoping to recoup some of its art debt. The series showed up at the Gagosian Gallery in New York in 1994 with a price tag of $14 million, but didn't get sold and wound up going back to Japan.

Cut to 1998. The yen is falling, making it easier for Japanese sellers to unload art at less of a loss. The country's government is leaning on finance companies to get bad loans off their books. Once again, Lake takes a look at the art market. Both Christie's and Sotheby's peg the value of Magritte's work at around $5 million, which is a little too low for Lake.

But a California dealer (who shall remain anonymous) caught the ear of a local investor who, like so many art speculators before him, had money and knew that art had some value. The dealer set about interesting the auction houses, calling Sotheby's and Christie's, which again put the series' value at around $5 million. Along the way, Christie's either agreed to or proposed a more tempting solution. Sell the series piecemeal, one by one, and they'd be worth a whole lot more. There are many more people out there willing to pay a million or two for one Magritte painting than there are willing to pay $5 million for a series.

With Christie's committed to a substantial estimate of at least $11 million, the California dealer pulled the trigger on the deal, buying the eight canvases for around $6.5 million at the beginning of May. The paintings were rushed to New York in time to go on Christie's walls during the firm's 19th- and 20th-century auction previews and wound up in the Christie's London July 1 sale.

Separating domaine's canvases isn't a horror on the magnitude of breaking up an illuminated manuscript to sell the paintings individually, though it does go against the grain. Does it really matter? After all, each of the paintings is signed, and Magritte sold the gouaches for them individually. Certainly, some purists find it in poor taste, and one dealer, who would probably do the same thing, given the chance, said, "It's intended to be one work. It's a retrospective. Each of the paintings is composed of a number of images -- it's surprising that instead of selling the eight paintings they didn't cut them up and sell the images separately!"

One of the larger ironies here is that a Japanese finance company -- hardly a protector of Western art traditions -- didn't even consider splitting up the works. Leave it to an American investor, guided by an American dealer and abetted by a British auction house, to dismantle an artwork's integrity.

The other irony, of course, is that the auction houses say that speculators are bad for the market. The flood of money that comes from speculators destabilizes the market in the long run, first inflating prices and then, when markets head south, deflating it even further with bankruptcy sales.

All of which is true. And none of which seems to matter when a potential profit is dangling just before an auction house's eyes. The auction houses may not like speculators, but they need them, just as much as they need to find grist to run through their mills.

ANDREW DECKER writes on art and the art market.