Hi,

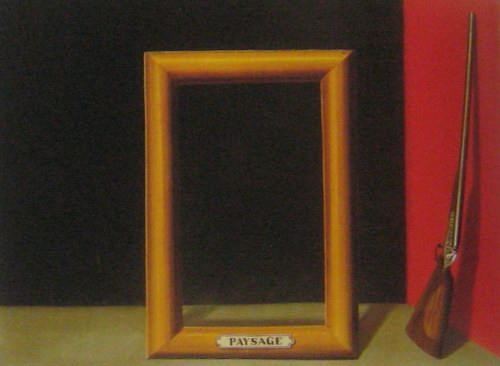

The next series of blogs features article Magrittes painting within a painting series. These paintings typically use an eisel with a canvas in front of an open window. The first painting within a painting was the 1931 The Fair Captive (La Belle Captive) series followed by the 1933 The Human Condition (La condition humaine) series. In both series Magritte investigated the paradoxical relationship between a painted image and what it conceals. Magritte might have learned the theme from illustrations in A. Cassagne's Traité pratique de perspective (1873), a book used at the Académie Royale des Beaux Arts when Magritte was a student there. Magritte did a similar type of investigation with windows. Sometimes the window is broken and image outside is also shattered. Let's look at Magritte's 1933 painting, The Human Condition:

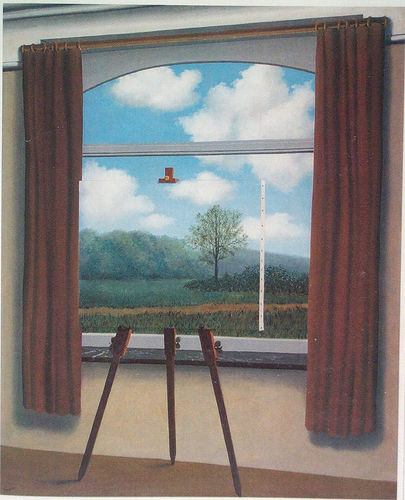

The Human Condition- 1933

This is how Magritte himself explained the painting, "The problem of the window let to La Condition Humane. In front of a window as seen from the interior of the room, I placed a painting (canvas and easel) that represented precisely the portion of landscape blotted out by the painting. For instance the tree represented in the painting displaced the tree behind the painting outside the room. For the viewer the tree was simultaneously inside the room, in the painting outside the room, in the real landscape, in thought."

Magritte continues, "Which is how we see the world, namely, outside of us; although having only one representation of it within us. Similarily we sometimes remember a past event as being in the present. Time and space lose meaning and our daily experience becomes paramount." [Reworded from a 1951 printing]

"This is how we see the world. We see it outside ourselves, and at the same time we only have a representation of it in ourselves. In the same way, we sometimes situate in the past that which is happening in the present. Time and space thus loose the vulgar meaning that only daily experience takes into account."

"Questions such as 'What does this picture mean, what does it represent?' are possible only if one is incapable of seeing a picture in all its truth, only if one automaically understands that a very precise image does not show precisely what it is. It's like believing that the implied meaning (if there is one?) is worth more than the overt meaning. There is no implied meaning in my paintings, despite the confusion that attributes symbolic meaning to my painting.

How can anyone enjoy interpreting symbols? They are 'substitutes' that are only useful to a mind that is incapable of knowing the things themselves. A devotee of interpretation cannot see a bird; he only sees it as a symbol. Although this manner of knowing the 'world' may be useful in treating mental illness, it would be silly to confuse it with a mind that can be applied to any kind of thinking at all." -excerpt from Magritte's letter to A. Chavee, Sept. 30, 1960

"I have a great idea (not earth shattering) about the naive question, 'What does this picture represent?' My idea is that the questioner sees what it represents, but he wonders what represents the picture, and faced with the difficulty of figuring it out from this direction, he finds it easier and more fitting to ask what the picture 'represents.'

What represents the picture are our ideas and feelings--in short, whoever is looking at the picture is representing what he sees. This idea is not, some say, within the realm of knowledge, so it won't help me protect myself when the occasion arises."--excerpt from Magritte's letter to Paul Colinet, 1957

Below is an abstract by Eric Wargo:

Infinite Recess: perspective and play in Magritte's La Condition Humaine

by Eric Wargo

ABSTRACT: The paintings of Rene Magritte, with their unsettling of common-sense relationships among objects, images and words, have been compared by many critics to the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein. The 1933 painting La Condition Humaine, for instance, depicts a painting that exactly covers a 'real' landscape outside a window – thus raising questions about the 'location' of perception and thought. But Magritte's uncanny use of perspective, and his depictions of spaces that have ambiguous depth, suggest that an equally helpful interpretive framework to that of Wittgenstein may be that of psychoanalysis, particularly the object-relations theory of D.W. Winnicot and the latter's concept of 'transitional phenomena'. La Condition Humaine, for example, exemplifies how, by both negating and affirming the opacity of the picture plane, perspective transforms the painting into a transitional object that is both 'there' and 'not there' simultaneously. Many of the painter's works, his 'window' series in particular, suggest approaching Albertian perspective itself as a question of object-relating, the simultaneous search for autonomy and ontological security through play. An understanding of how Magritte's ambiguous spaces suggest both security as well as open-ended possibility can help to link his work not only with the traditions of Renaissance perspective and its modernist critics, but also with the aesthetic of the sublime and its iconography of colossal, indifferent nature. Sublimity may be interpreted psychoanalytically as nostalgia for the scale of childhood experience – for the world viewed as an enormous room in which small objects assume monumental physical and symbolic proportions.

Suzi Gablik in her books on Magritte affirms, “For example, The Human Condition I actually formulates the contradiction between three-dimensional space, which objects occupy in reality, and two dimensional space of the canvas used to represent it. The ambiguity in Magritte’s image suggests that something is irreconcilable in the confrontation between real space and spacial illusion. In this single image he has defined the whole complexity of modern art— a complexity which has lead to a devaluation of the imitation of nature as the basic premise of panting.”

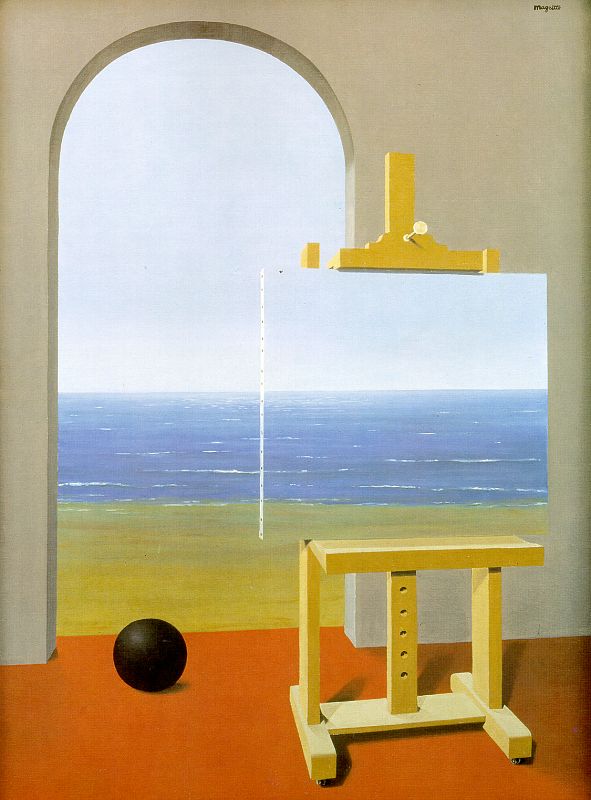

Human Condition II- 1935

Here's an article about the second 1935 version: Magritte liked to pull the same stunt in several of his paintings. He painted the room, the ball on the floor, and the artist's easel realistically and then used an internal framing device (that of the painting on canvas being in perfect horizontal line with the horizon of the actual ocean) to deny that this latter item was an accurate representation of the ocean view. In these Ceci n'est pas works, Magritte seems to suggest that no matter how closely, through realism-art, we come to depicting an item accurately, we never do catch the item itself, per se, as a Kantian noumenon, but capture only an image on the canvas. We, as humans, are always striving to duplicate (connect with) what we see in reality (such as on canvas) and it's impossible to do so.

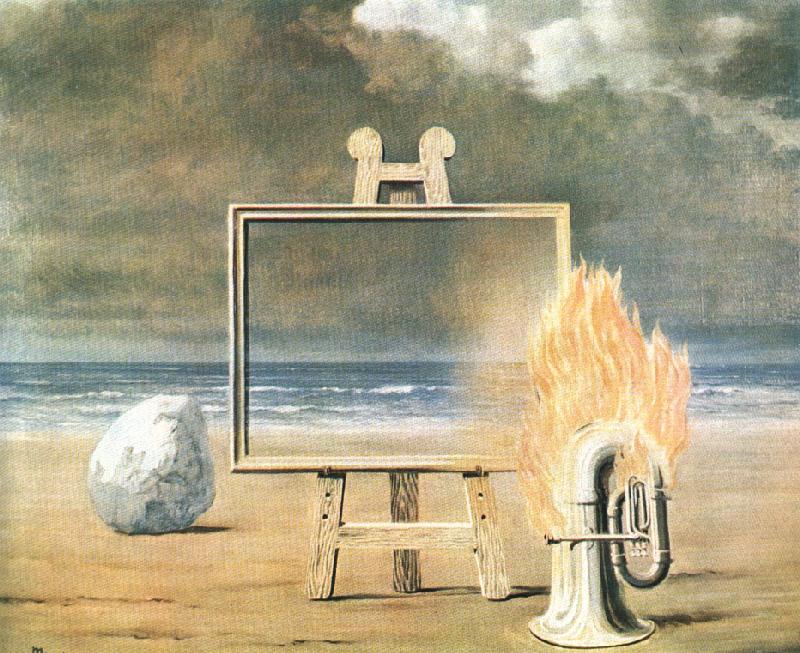

1947 Fair Captive (La Belle Captive) Another Series of Magritte's paintings within a painting

Magritte based a lot of his works on the concepts put forth by the philosopher Immanuel Kant and that is: "Humans can make sense out of phenomena in various ways, but can never directly know the noumena, the "things-in-themselves," the actual objects and dynamics of the natural world. In other words, our minds may attempt to correlate in useful ways, perhaps even closely accurate ways (such as through a painting), with the structure and order of the various aspects of the universe, but cannot know these "things-in-themselves"(noumena) directly."

The Delights of the Landscape

A CONTINUAL PREOCUPATION FOR THE SURREALISTS WAS THE METAPHYSICAL, OR THE UNPICKING OF A PRIORI ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT THE ILLUSIONARY DEPICTION OF REALITY.

In so much of his work, Rene Magritte wittily plays with these perceptions by adressing the problem laterally. In the Human Condition II, Magritte exemplifies the contraditions between the three-dimensional space and the limits of a two-dimensional canvas. More importantly the title refers to the relationship that humans have with those contraditions as part of the “the human condition”. As such Magritte continues the process of questioning the assumptions of Renaissance ideas of painting being a ‘Window on reality’, which had already begun to be debunked by Picasso and Braque in their CUBIST ‘laboratory’. For Picasso ‘reality was in the painting’, replacing trompe-l’oeil for what he called trompe-l’esprit.

The Human Condition II, was a variant of a painting executed in 1933, in which he began to explore the ideas around the theme of inside and outside. In the first version the painted canvas is placed in front of a glazed window. The second version adds another playful twist to the original, by siggesting that the viewer is already outside, looking through a trompe-l’oeil archway.

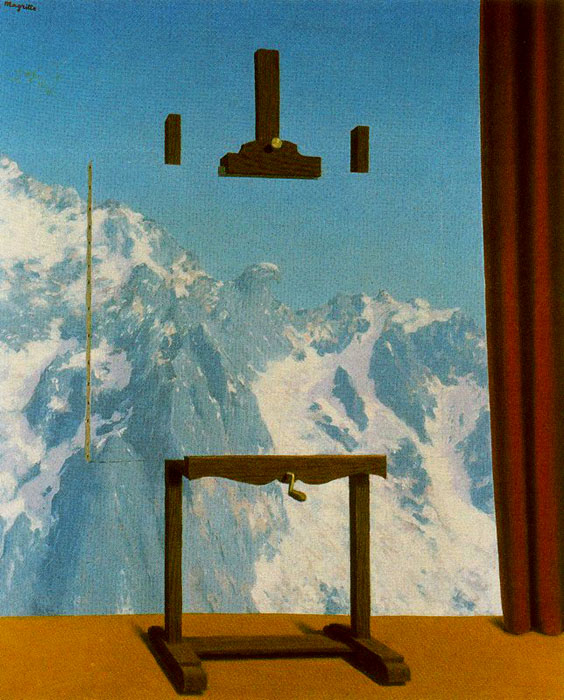

The Call of the Peaks (La Llama de la Cimas) 1943

Here's an article about an 1987 exhibiton, "The Window in 20-Century Art", that mentions Magitte's window painting Evening Falls:

ART: 'THE WINDOW' IN 20TH-CENTURY WORKS

By VIVIEN RAYNOR Published: Friday, January 2, 1987

On view at the Neuberger Museum of the State University of New York at Purchase, ''The Window in 20th-Century Art'' sounds like but is not an inventory. On the other hand, the project may well have started out that way, for it has the feel of an idea that grew and changed shape in the course of its realization.

Organized by the museum's director, Suzanne Delehanty, the show consists of about 80 paintings and sculptures, most of them done by Americans working in the second half of the century. Its range is, nevertheless, remarkable - from a small Vuillard, circa 1900, of a window looking out onto a garden, to a couple of Joseph Cornell boxes; from Edward Hopper's voyeuristic ''Night Windows'' to Marcel Duchamp's ''Fresh Widow,'' a miniature set of French windows with panes ''glazed'' in black leather that is a 1964 replica of the 1920 original.

There are windows reflected on the grass at night (Robert Berlind), and on a polished wood floor in the daytime(Sylvia Plimack Mangold); windows implied - a classic Mark Rothko - and a splashy blue rectangle on a white ground that was done by Gene Davis in his Abstract Expressionist period. Add to these, analogies for windows such as Roy Lichtenstein's painting of a stretcher frame, complete with wedges, and Eva Hesse's wash drawings of positive and negative grids.

With his ''Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even'' painted on glass, Duchamp shares - with Christo, who is represented by one of his 1960's storefront mockups - the prize for the most real window. Competing for ''most realistic'' window are the photographic painters Richard Estes and Don Eddy with, respectively, a row of telephone booths outside a glass and metal diner, and a store window crammed with awful shoes. The shoes seem to rivet the attention of Henry Geldzahler, whose 1968-69 portrait by David Hockney hangs opposite.

But they won't do so for long since it's obvious that the then-champion of Pop, who sits at the exact center of a voluptuous pink sofa with Manhattan visible through the dusty window behind him, is about to give audience to young Christopher Scott, who stands at attention to his left. Balthus's young woman seems ready to leave her room by way of the window, perhaps to elude the assailant who has bared one of her breasts. Magritte's green apple, on the other hand, has grown too large to escape its space -through either the window or the door that it is presumably obstructing.

A show that encompasses Robert Delaunay, Richard Diebenkorn, Neil Jenney, Ellsworth Kelly, Matisse, Robert Motherwell and Picasso, among others, it is essentially a survey of individualism, and as such resists grading. But as far as the theme is concerned, Magritte is the star with his ''Evening Falls.'' This is the famous canvas that would have been a picture of a sunset painted on a window, except that the window has been shattered. Accordingly, the simulacrum lies in pieces on the floor, while the original outside remains intact.

A verbal-visual pun that brings on intellectual vertigo if contemplated too long, the work is the anthology's clincher. Still, only those privy to the catalogue essays by the curator and by Shirley Neilsen Blum, who teaches art history at the state university, would know it and therefore realize that the exhibition actually stands for the denouement of a drama that began with the Renaissance. For it was then that the canvas was first treated as a window and that artists, intoxicated by the invention of perspective, painted the world as if they viewed it through a window. And, as Ms. Blum points out, it's a tidy little world with a place for everything, human and divine, and an abundance of windows, most of which frame peep shows replete with moral implications.

The canvas-as-window concept persisted until the late 19th century, but by the Baroque period, the windows depicted are less likely to enclose moral lessons than to be the sources of the light that illuminates morality, as in the work of Rembrandt and Zurbaran. Languishing during the 18th century, the image made a comeback during the romantic era, but its trail is hard to follow. Ms. Blum cites Caspar David Friedrich for treating the window as a kind of partition between the real and the ineffable, but doesn't comment on romantics such as Delacroix and Turner, who, more or less his contemporaries, seem to have ignored its significance altogether.

Their essays overlapping, the writers differ slightly as to the window's importance to the Impressionists and their successors. But they agree that while perspective, already moribund by the late 1800's, died well before World War I (its tyranny replaced by that of the artists, notes Ms. Blum), the window lives on.

The question is whether the device has any special significance today -with or without perspective. Not surprisingly, Ms. Delehanty says it has and, in her essay, charts the ups and downs of its survival in some detail, taking note of its rejection by some though not all of the Cubists, its transformation by Matisse, its rejection again by the Formalists and, finally, the acceptance it is currently enjoying. She also takes care of a myriad of loose ends, including those contemporaries who take the Renaissance tradition seriously and those who use it to ironic ends.

The historian who would impose order on chaos risks tortuousness, and Ms. Delehanty is no exception. There are moments when the reader is hard put to tell whether she is discussing the format or the object itself. More perplexing, though, is that both writers, having given the familiar story of disintegration a new twist, should resort to the convention of an upbeat ending, as if the very individualism that had caused the chaos will some day, somehow cure it.

A show that is as stimulating as the arguments for it, ''The Window'' closes at the Neuberger on Jan. 18. It then reopens at Houston's Contemporary Arts Museum in April. Also of interest this week: John Alexander (Marlboro Gallery, 40 West 57th Street): John Alexander is a figurative Expressionist who keeps a foot in the Abstract Expressionist camp. Which is to say that his scenes - a banquet, a dance, a cockfight, tropical swamps inhabited by brightly colored birds and fish - are deliberately composed. And for all their apparent spontaneity, his impastoes of rich color are consciously and skillfully applied. The automatism is in the slanting lines with which the artist garnishes the finished work. In images such as the crucifixion - where the figure, a black man wearing little more than tribal markings, is surrounded by baboons similarly adorned - the mannerism works if only because the lines, despite the birds perched on them, suggest spears. It also heightens the menace of the dark woods filled with bogymen that are closing in on a white woman in full bridal fig. She appears not to have all her oars in the water, which may explain the scene's title, ''Waiting in the Wrong Woods.'' But in ''Christina's World,'' which features a black queen who, attired in sumptuous yellow robes, sits on a throne holding a green monkey on her lap, the lines are a tiresome distraction.

Alexander paints and draws animals with genuine affection, but, like Donald Roller Wilson, he also uses them to emphasize the satirical thrust of his figure compositions and frequently cartoons his black figures for the same purpose. Each of the black priests watching monkeys advance on the corpse of a white burgher-type man lying in state has the same all-purpose caricature for a face. The artist himself is black, and it is black subject-matter (if not always black subjects), animals and in particular the skull of a deer that have inspired the best paintings. (Through Saturday.) Justen Ladda (Museum of Modern Art): The third in the museum's Projects series, Justen Ladda's installation is titled ''Art, Fashion and Religion.'' Ladda is yet another young artist impelled to expose the self-evident - in this case, that consumerism makes the world go round. But visually, at least, he does so with a touch of humor.

Visitors enter the installation through a mazelike passage, the white walls of which are divided at waist height by a continuous band of Greek-key ornamentation made of wood painted black. Every few feet the frieze is interrupted by a frame containing a bunch of pale green grapes painted on a white ground. The bunch diminishes grape by grape until nothing is left but the black stalks - ''a souvenir of the act of eating,'' according to the brochure statement contributed by Wendy Weitman, who is assistant curator in the museum's department of prints and illustrated books.

By now, the spectator has reached the semicircular room containing the main attraction. This is a tableau deployed on a floor paved with asymmetrical wood crosses - chunky variations on the swastika, painted bright colors. The white walls are patterned with lines of regular crosses in black and are flanked with plain white columns. In the middle is Michelangelo's Pieta sprayed in gray over a pile of empty white cardboard boxes. Lurking between the columns, meanwhile, are female store-dummies clad in black or gold lame suits, and the whole scene is illuminated by spotlights and fluorescent bars of deep purple.

Once again, Miss Weitman comes to the rescue. ''The fast changing trends we have come to accept in fashion,'' she says, ''have become the norm in contemporary society's attitudes toward art and religion.''

The giant housefly that Ladda installed in an empty swimming pool for a 1982 show at Wave Hill may or may not have been a comment on what he calls ''belief systems.'' But the Museum of Modern Art production leaves no doubt that the artist is now one of a growing band intent on using Pop Art to didactic ends. It is enough to make survivors of the original Pop feel like old Regency rakes confronted by the dawn of the Victorian era. (Through Tuesday.)