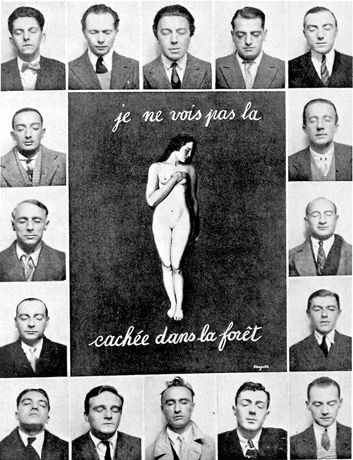

This is the 1929 "Second Manifesto of Surrealism" published 5 years after the First Manfesto. It appeared in the the twelfth and final issue of La Révolution surréaliste (December 15, 1929).

The Cover of La Révolution surréaliste featuring Magritte's "Hidden Woman"

Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1929)

We combat, in whatever form they may appear, poetic indifference, the distraction of art, scholarly research, pure speculation; we want nothing whatever to do with those, either large or small, who use their minds as they would a savings bank. All the forsaken acquaintances, all the abdications, all the betrayals in the book will not prevent us from putting an end to this damn nonsense. It is noteworthy, moreover, that when they are left to their own devices, and to nothing else, the people who one day made it necessary for us to do without them have straightway lost their footing, have been immediately forced to resort to the most miserable expedients in order to reingratiate themselves with the defenders of law and order, all proud partisans of leveling via the head. This is because unflagging fidelity to the commitments of Surreal-ism presupposes a disinterestedness, a contempt for risk, a refusal to compromise, of which very few men prove, in the long run, to be capable. Were there to remain not a single one, from among all those who were the first to measure by its standards their chance for significance and their desire for truth, yet would Surrealism continue to live. In any event, it is too late for the seed not to sprout and grow in infinite abundance in the human field, with fear and the other varieties of weeds that must prevail over all. This is in fact why I had promised myself, as the preface for the new edition of the Manifesto of Surrealism (1929) indicates, to abandon silently to their sad fate a certain number of individuals who, in my opinion, had given themselves enough credit: this was the case for Messrs. Artaud, Carrive, Delteil, Gérard, Limbour, Masson, Soupault, and Vitrac, cited in the Manifesto (1924), and for several others since. The first of these gentlemen having been so brazen as to complain about it, I have decided to reconsider my intentions on this subject:

"There is," writes M. Artaud to the Intransigeant, on September 1o, 1929, "there is in the article about the Manifesto of Surrealism which appeared in l'Intran last August 24, a sentence which awakens too many things: 'M. Breton has not judged it necessary to make any corrections —especially of names—in this new edition of his work, and this is all to his credit, but the rectifications are made by themselves.' " That M. Breton calls upon honor to judge a certain number of people to whom the above-named rectifications apply is a matter involving a sectarian morality with which only a literary minority was hitherto infected. But we must leave to the Surrealists these games of little papers. Moreover, anyone who was involved in the affair of The Dream a year ago is hardly in a position to talk about honor.

Far be it from me to debate with the signatory of this letter the very precise meaning I understand by the term "honor." That an actor, looking for lucre and notoriety, undertakes to stage a sumptuous production of a play by one Strindberg to which he himself attaches not thhe slightest importance, would of course be neither here nor there to me were it not for the fact that this actor had upon occasion claimed to be a man of thought, of anger, of blood, were he not the same person who, in certain pages of La Révolution surréaliste, burned, if we can believe his words, to burn everything, who claimed that he expected nothing save from "this cry of the mind which turns back toward itself fully determined desperately to break its restraining bonds." Alas! that was for him a role, like any other; he was "staging" Strindberg's The Dream, having heard that the Swedish ambassador would pay (M. Artaud knows that I can prove what I say), and it cannot escape him that that is a judgment of the moral value of his undertaking; but never mind. It is M. Artaud, whom I will always see in my mind's eye flanked by two cops, at the door of the Alfred Jarry Theatre, sicking twenty others on the only friends he admitted having as lately as the night before, having previously negotiated their arrests at the commissariat, it is M. Artaud, naturally, who finds me out of place speaking of honor.

Aragon and I were able to note, by the reception given our critical collaboration in the special number of Varietés, "Le Surréalisme en 1929," that the lack of inhibition that we feel in appraising, from day to day, the degree of moral qualification of various people, the ease with which Surrealism, at the first sign of compromise, prides itself in bidding a fond farewell to this person or that, is less than ever to the liking of a few journalistic jerks, for whom the dignity of man is at the very most a subject for derisive laughter. Has it really ever occurred to anyone to ask as much of people in the domain—aside from a few romantic exceptions, suicides and others—heretofore the least closely watched! Why should we go on playing the role of those who are fed up and disgusted? A policeman, a few gay dogs, two or three pen pimps, several mentally unbalanced persons, a cretin, to whose number no one would mind our adding a few sensible, stable, and upright souls who could be termed energumens: is this not the making of an amusing, innocuous team, a faithful replica of life, a team of men paid piecework, winning on points?