Hi,

This 1992 article provides some insight into Magritte's mother's suicide:

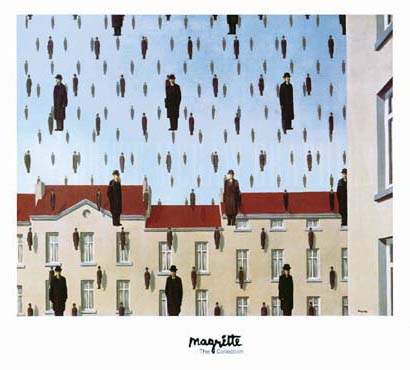

Bowler-Hatted Men, Raining From the Sky

By Michael Kimmelman chief art critic of The New York Times.

Published: Sunday, November 29, 1992

RENE MAGRITTE Catalogue Raisonne. Volume One: Oil Paintings, 1916-1930. By David Sylvester and Sarah Whitfield. Edited by David Sylvester. Illustrated. 388 pp. New York: The Menil Foundation/Philip Wilson Publishers/ Rizzoli International Publications. $180. MAGRITTE The Silence of the World. By David Sylvester. Illustrated. 352 pp. New York: The Menil Foundation/Harry N. Abrams. $75.

SERIOUS opinion has always been sharply divided about Rene Magritte. Some, like the French philosopher Michel Foucault, regarded him as a modern master. Others, like Thomas Hess, the influential American art critic, dismissed him in 1954 as a "peripheral" figure even among the Surrealists.

What is indisputable is that Magritte's paintings of trains steaming out of fireplaces and bowler-hatted men raining from the sky have become some of the most famous and frequently reproduced images in modern art. In 1958 it was still possible for one Larousse reference book to exclude Magritte, even though it listed his Belgian Surrealist colleague, Paul Delvaux. Today, Magritte's popularity is such that a retrospective of his art recently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was visited by as many as 11,000 people a day (the famously crowded landmark Matisse exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art has 7,000 ticketed visitors each day).

And with the latest publications by David Sylvester and Sarah Whitfield, two English art historians and critics, he has been honored with the painstaking scrutiny accorded the most prized artists of the century. Excellent monographs -- like the one by Suzi Gablik in 1970 -- have been written about him in the past. But the new books are far and away the most important.

The first of five projected volumes of a catalogue raisonne of Magritte's art, written by Mr. Sylvester and Ms. Whitfield and edited by Mr. Sylvester, deals with the paintings of 1916 to 1930, encompassing the feverishly creative years of 1925 to 1930, when many of his signature motifs and ideas emerged. The book is the product of more than two decades of research. (The entire project, it should be said, has been underwritten by the Menil Foundation in Houston, which owns many works by Magritte.)

This volume, extensively illustrated in black and white, documents the eclectic sources for Magritte's art. They range from a fresco by Fra Angelico to an illustration from a medical encyclopedia to the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, whose lead Magritte was to follow often. The book includes information about the condition and history of every painting. And it begins with a 120-page chronology of the artist's early life that is a model in its detail and lucidity. For serious students of the first phase of the artist's career, the book is indispensable.

For a more general readership, "Magritte," a catalogue by Ms. Whitfield accompanying the exhibition that was at the Hayward Gallery in London and at the Metropolitan, and which now has moved on to Houston and Chicago, offers a concise although still elaborate chronology of Magritte's entire life, and color photographs of 168 of his most important works with a brief commentary about each one. (Published in London by the South Bank Center, this "Magritte" is available in American museum bookstores; the price is $49.50 in cloth, $35 in paper.)

An introductory essay traces the history of the artist's reputation, which, the author admits, "has suffered from the tendency of critics to see him as a case apart, a painter of the modern age who has no place in the mainstream of modern art." Ms. Whitfield argues that because he absorbed the lessons of Cubism, because of his use of collage and because he frequently expressed "a profound uncertainty about the nature of existence" in his art, Magritte was actually very much a mainstream modernist. To underscore the point, she cites artists and writers in his debt, including the Pop artists for whom he had little regard. A second introductory text brings together extracts from writings about him by fellow Belgian Surrealists and others.

Ms. Whitfield's book is a helpful companion to the exhibition, but those looking for a thorough overview of Magritte's art cannot do better than Mr. Sylvester's "Magritte: The Silence of the World." Whereas the catalogue raisonne sticks to facts, this monograph, in the form of an extended and highly personal essay rather than a strict biography, puts forward evaluations and interpretations of the works that are distinguished by their insight, sobriety and clarity.

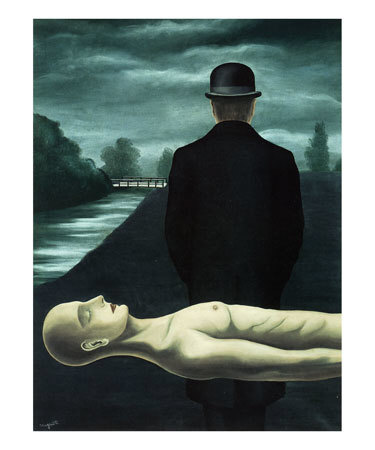

Mr. Sylvester has tracked down a wealth of new information, including the circumstances of the suicide by drowning of Magritte's mother, who, the artist once said, was recovered from the river Sambre in Chatelet with her face covered by her nightdress. That memory, which Mr. Sylvester makes clear was almost certainly a fantasy originating with the artist's governess, has often been cited as a source for the recurrent paintings of bare-chested women and hooded figures.

The author is appropriately circumspect about the story, while acknowledging its poetic significance: "Perhaps through acceptance of his governess's account of his mother's suicide, Magritte had perhaps been haunted for years by such images. Perhaps he had nursed a more general idea of the covered face and perhaps of the body laid naked and gave form to the idea only when he came to do these pictures. Perhaps such images were not associated in his mind with his mother's death until he did these pictures. Perhaps he did not associate these pictures with his mother's death at all. . . . Perhaps the whole invention of that story of the suicide came out of an obsession with covered faces which was part of an obsession with the hidden which undoubtedly . . . did haunt him."

Photo: "The Musings of a Solitary Walker," 1926, by Rene Magritte. (From "Magritte: The SIlence of the World")

About Magritte's 45-year marriage to Georgette Berger, Mr. Sylvester not only offers intimate details but also links them, often inventively, to the art: "She seems," he writes in one case, "to have been both daughter and mother to him. In that sickening image he made in which the head of a mother has switched places with that of the infant son in her arms, perhaps he was alluding unconsciously to his marriage."

And Mr. Sylvester writes with authority and deliberateness about the sources of Magritte's art, the characteristic frontality of his images, his deliberately neutral, just-the-facts style of painting, and the curious vache pictures of 1948 -- jokingly mimicking such artists as Ensor, Daumier and Renoir -- in which he temporarily threw over that style for something outrageous and provocative. He convincingly describes the quasi-Fauve and quasi-Impressionist vache works, which have traditionally been considered merely aberrant, as consistent with the rest of his art. "They did not represent an abandonment of his general attitude to style," Mr. Sylvester observes. "That attitude was essentially an opposition to style for art's sake and to style as an ego trip for the mandarin artist. In their different ways the styles of the aberrant periods were both demotic styles. The vache style was obviously that, since it was founded on popular art of the basest kind and had all the attributes of a pictorial slang."

For this artist's devotees, "Magritte: The Silence of the World," which is also notable for being beautifully and elaborately illustrated, will be a fitting tribute. As for detractors who see him, instead, as the source of a few memorable images and ideas, this book may well leave them impressed more by the author than by his subject.