Hi,

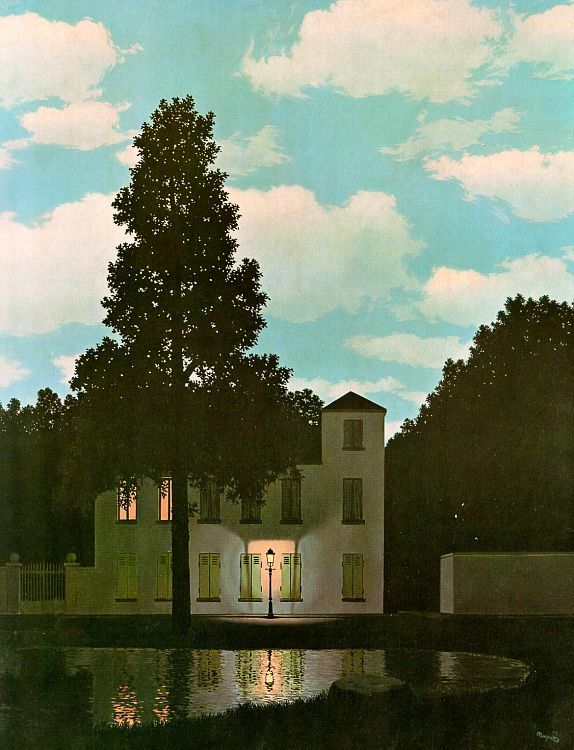

In this blog we'll look at Magitte's most popular series of paintings L'Empire des Lumieres (Empire of the Lights). Below is a version done in 1967 the year of his death. The uncompleted painting would remain on its easel in the painter's house in Brussels until the death of Georgette Magritte in 1986.

Margitte's last painting (unfinished) was his 1967 version of Empire of the Lights

Between 1949 and 1964, Magritte made seventeen oils and ten gouache versions of L'Empire des lumières, one of his most famous and sought-after themes, each of which displays some variation on a dimly lit nocturnal street scene with an eerily shuttered house and glowing lamppost below a sunlit blue sky with puffy white clouds.

Magritte explained the origin of the image in a radio interview in 1956, stating: "What is represented in a picture is what is visible to the eye, it is the thing or the things that had to be thought of. Thus, what is represented in the picture [L'Empire des lumières] are the things I thought of, to be precise, a nocturnal landscape and a skyscape such as can be seen in broad daylight. The landscape suggests night and the skyscape day. This evocation of night and day seems to me to have the power to surprise and delight us. I call this power: poetry" (quoted in D. Sylvester, op cit., p. 145).

According to Roisin (and I agree) the painting L'empire des lumières (the empire of the lights, figure.8) was inspired in Magritte by a poem of Lewis Carroll:

"... the sun on the sea was shining/ it shone with all its forces/ it did its best to reflect the sparkling and calm waves/ and it was very odd, you see, because/ it was in the middle of the night."

The first painting from this series (Sylvester, no. 709) depicts a somewhat urban street with a couple of houses and an off-center streetlight. This composition was immediately popular with Magritte's collectors, and was purchased by Nelson Rockefeller in January of 1950. Although Magritte initially preserved this format (fig. 1), by 1951, he had switched this scene to a more rural setting (Sylvester, no 768), depicting a manor house lit from within and introducing the enormous conical tree that also dwarfs the large house in the present work.

The above version of Magritte’s L’Empire des lumières, which brought $3,554,500, was one of the only works from the Alice Lawrence collection to fare well in a recent Christie auction.

From the Peggy Guggenheim Collection:

The detailed brushstrokes give the painting the appearance of a photograph. They are smooth, so the individual brushstrokes are not seen. It seems almost as if the viewer were looking through a window rather than a work of art. The painting is very 3 dimentional in that there is a foreground and a background and a middle ground. The placing with the house in the center and the tree ont hre left of it with the sky on the top and the water beloww creates a calming atmosphere. The water looks as if it is moving because of the speckeled reflections of the house and tree. The bright baby blue sky contrasts the dark gray house, trees and water. The foreground helps lead the viewer's eye up to the light.The sky takes up almost half of the painting, causing the tall tree in the middle to stand out, and the tree leads the viewer's eye down to the light by the door and water.The sky gives the appearance of daytime because it is light, while the rest of the painting seems to be night because it is dark and black. The painting is almost monocromatic, having only blue, white, black, and yellow/gold. The painting gives off a sense of serenity, and calmness because it is still and quiet. It gives the appearance of either a warm summer night because the sky stays lighter later, or a cold winter morning because the sky gets light earlier. The detailed sky, with the realistic clouds,could be representing heaven. This painting represents Surrealism, because it is a mix of the real world (everything in it could be seen in real life) and the unconcious mind (the objects are placed in a non realistic fashion). The scene could not possibly be depicted in real life, because the sky is a different time of day than the rest of the painting, which shows that it is definately a surrealist painting.

Another L'Empire des lumières

The major gouache seen here is similar to versions in oil that Magritte executed in 1954 (fig. 2; Sylvester, nos. 804, 809-810), when collectors were clamoring for further interpretations of this image. The painter increased the size of these works, and selected a vertical format, thus focusing attention on a single dollhouse-like residence whose tightly shuttered first floor is illuminated by lamplight. The glowing second floor windows are obscured by the lowest branches of the tall tree that stretches into the daytime sky. The markedly increased psychological tension of these works from the mid 1950s illustrates Siegfried Gohr's conviction that, by repeating and reinterpreting successful themes, Magritte was "arranging and rearranging visual elements until they produced a shock like a blow from a boxer's glove--whose force, however, remained purely visual and mental" (in Magritte, exh. cat., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2000, p.17). Indeed, this version of L'Empire des lumières best instantiates the uncomfortable if not threatening idea of domesticity that can be found in works by his contemporary Louise Bourgeois (fig. 3). Magritte's mysterious house was also fundamental to the development of early works by Vija Clemins such as House #1 (fig. 4), a house-shaped box that opens to reveal fiery orange tufts of fur.

Magritte's friend, the Belgian poet and philosopher Paul Noug (1895-1967) suggested the title for this image, playing on the double meaning of l'empire ('dominion') as 'territory' and 'dominance.' Noug was undoubtedly sensitive to Magritte's conviction that his paintings never expressed a singular idea, but rather were a form of stimulus that created new thoughts in the mind of the viewer. "Titles play an important part in Magritte's paintings," stated the poet, "but it is not the part one might be tempted to imagine. The title isn't a program to be carried out. It comes after the picture. It's as if it were its confirmation, and it often constitutes an exemplary manifestation of the efficacy of the image. This is why it doesn't matter whether the title occurs to the painter himself afterwards, or is found by someone else who has an understanding of his painting. I am quite well placed to know that it is almost never Magritte who invents the titles of his pictures. His paintings could do without titles, and that is why it has sometimes been said that on the whole the title is no more than a conversational gambit" (quoted in Sarah Whitfield, Magritte, exh. cat. The South Bank Centre, London, 1992, p. 39). Indeed, when Paul Colinet, one of Magritte's closest friends, ventured a definitive explanation for the imagery of L'Empire des lumières, Magritte confided to another friend, "The attempt at an explanation (which is no more than an attempt) is unfortunate: I am supposed to be a great mystic, someone who brings comfort (because of the luminous sky) for unpleasant things (the dark houses and trees in the landscape). It was well intentioned, no doubt, but it leaves us on the level of pathetic humanity" (quoted in H. Torczyner, Magritte, Ideas and Images, New York, 1977, n.p.).

By including day and night, two normally irreconcilable conditions, within a spatially continuous scene, Magritte disrupts the viewer's sense of time. "After I had painted L'empire des lumières," he recalled to a friend in 1966, "I got the idea that night and day exist together, that they are one. This is reasonable, or at the very least it's in keeping with our knowledge: in the world night always exists at the same time as day. (Just as sadness always exists in some people at the same time as happiness in others.) But such ideas are not poetic. What is poetic is the visible image of the picture" (quoted in ibid.). André Breton also recognized in this work the unconventional reconciliation of opposites that the Surrealists prized, stating: "To [Magritte], inevitably, fell the task of separating the 'subtle' from the 'dense,' without which effort no transmutation is possible. To attack this problem called for all his audacity--to extract simultaneously what is light from the shadow and what is shadow from the light (l'empire des lumières). In this work the violence done to accepted ideas and conventions is such (I have this from Magritte) that most of those who go by quickly think they saw the stars in the daytime sky. In Magritte's entire performance there is present to a high degree what Apollinaire called "genuine good sense, which is, of course, that of the great poets" (A. Breton, "The Breadth of Rene Magritte" in Magritte, exh. cat., Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock, 1964, n.p.).

Anotehr Version

L'EMPIRE DES LUMIERES" 1952

oil on canvas 39 3/8 x 311/2 in. (100 x 80 cm.) Painted in 1952 PROVENANCE Iolas Gallery, New York. Dominique and Jean de Menil, New York (commissioned from the artist and acquired through the above). By descent from the above to the present owners. LITERATURE Letter from A. Iolas to R. Magritte, 23 June 1952. Letter from R. Magritte to A. Iolas, 9 July 1952. Letter from R. Magritte to A. Iolas, 30 July 1952. Letter from R. Magritte to A. Iolas, 1 October 1952. Letter from R. Magritte to A. Iolas, 8 January 1953. Letter from R. Magritte to M. Mari‰n, 27 July 1952, in R. Magritte (ed. M. Mari‰n), La Destination: Lettres … Marcel Mari‰n (1937-1962), Brussels, 1977, no. 258. Magritte, exh. cat., Hayward Gallery, London, 1992, no. 111 (illustrated in color). D. Sylvester, S. Whitfield and M. Raeburn, Ren‚ Magritte, Catalogue Raisonn‚, London, 1993, vol. III, p. 200, no. 781 (illustrated). EXHIBITION (?)New York, Iolas Gallery, Ren‚ Magritte, March-April, 1953. Dallas, Museum for Contemporary Art and Houston, Museum of Fine Arts, Ren‚ Magritte in America, December 1960-March 1961, no. 42. Minneapolis, Walker Art Center, The Vision of Ren‚ Magritte, September-October 1962, no. 36. Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Ren‚ Magritte, March-June 1998, p. 178, no. 175 (illustrated in color, p. 179). Humlebaek, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art; Edinburgh, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art; and The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (no. 54), Magritte, August 1999-September 2000, p. 80, no. 59 (illustrated in color).

NOTES: The Surrealists believed in the power of the subconscious. They considered it a repository of the dark and negative wills inherent in human nature, and the well-spring of creative activity. In an effort to render the dream concrete, Magritte turned toward a plastic figuration that deviated from the traditional beaux-arts academia. In this and other works by the artist, Magritte employed techniques that recall the characteristics of Freudian dream interpretation: bizarre juxtapositions, and irrational arrangements of perspective, lighting and atmosphere. Creating an element of subversion that so many of the Surrealists propagated, Magritte explored his subconscious - constantly awakening and reviving dreams. The present work belongs to a series of oils and goauches based on the contrast between daylight and darkness.

While Magritte's concerns lay deep within our use of language and our perceptions of reality, the concept intrigued Magritte. He once remarked, "I got the idea that night and day exist together, that they are one. This is reasonable, or at the very least it's in keeping with our knowledge: in the world, night always exists at the same time as day (Just as sadness always exists in some people at the same time as hapiness in others). But such ideas are not poetic. What is poetic is the visible image of the picture" (Letter from Magritte to M. Marion, 27 July 1952; see S. Whitfield, Magritte, London, 1992, no. 111). Magritte further explained the origin of the image in a radio interview in 1956: What is represented in the picture The Dominion of Light are the things I thought of, to be precise, a nocturnal landscape such as can be seen in broad daylight. The landscape suggests night and the skyscape day. This evocation of night and day seems to me to have the power to surprise and delight us. I call this power: poetry. (Quoted in D. Sylvster et al., op. cit., p. 145) Perhaps his most popular image, the title was suggested by one of the founders of the Surrealist movement, Paul Noug‚.

While the success of the title L'empire des lumiŠres lay in its expression of the ambivalent nature of reality itself, the title was often misunderstood and mistranslated to mean "empire" rather than "dominion". "English, Flemish and German translators take it in the sense of 'territory', whereas the fundamental meaning is obviously 'power', 'dominance'" (M. Mari‰n quoted in ibid., p. 145). As Andr‚ Breton wrote: Ren‚ Magritte's work and thought could not fail to come out at that opposite pole from the zone of facility - and of capitulation - that goes by the name of 'chiaroscuro'. To him, inevitably, fell the task of separating the 'subtle' from the 'dense', without which effort no transmutation is possible. To attack this problem called for all his audacity - to extract simultaneously what is light from the shadow and what is shadow from the light " L'empire des lumiŠres. In this work the violence done to accepted ideas and conventions is such (I have this from Magritte) that most of those who go by quickly think they saw the stars in the daytime sky. In Magritte's entire performance there is present to a high degree what Apollinaire called 'genuine good sense, which is, of course, that of the great poets'. (A. Breton, "The Breadth of Ren‚ Magritte", in Magritte, exh. cat., Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock, 1964) Invariably Surrealist landscapes are wrought with contradictions that are intended to arouse wonder as they defy comprehension. Though they may seem to spurn suggestions of a future and an ultimate order, L'empire des lumiŠres succeeds in reminding the viewer of the recurring, inescapable paradoxes of life itself.

In 1950, Dominique and Jean de Menil donated the second completed version of L'empire des lumiŠres to The Museum of Modern Art in New York (Sylvester 723). It met with great critical and public acclaim, and in 1952 the de Menils commissioned Magritte to paint the present work, the fourth completed version of this subject. Introduced by Alexander Iolas to many of the Surrealist artists, including Magritte, the de Menils assembled a vast collection of their paintings, sculptures and objects. Reluctant to be labeled as "collectors", the de Menils were actively and personally engaged with their art and emotionally powerful patrons who fostered the development of many artists. Dominique's claim of not to "know what Surrealism is" now seems redundant, as the de Menils built one of the most renowned collections in this field over the next forty years. (fig. 1) Ren‚ Magritte, circa 1960. SALESROOM NOTICE Additional EXHIBITION: London, The Hayward Gallery; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Houston, The Menil Collection; and The Art Institute of Chicago, May 1992-May 1993, no. 111 (illustrated in color). Additional LITERATURE: B. Levin, "Seeing is Disbelieving", The Times, 23 July, 1992, p. 12. M. Kimmelman, "Magritte in His Defiance of Life", The New York Times, 11 September 1992, p. C26.