Dada

Rene Magritte's experience with Dada was through his friend and accompliss ELT Mesens. A pianist and composer, Mesens intital contact was through Satie:

"With typical self-assurance Mesens introduced himself to Erik Satie, in April 1921, when the latter was performing in Brussels and made his first trip to Paris with Satie in December of that year. Satie, a humorist and poet as well as a composer, introduced Mesens into Dadaist circles, where he met Tristan Tzara, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Philippe Soupault, and lunched in Brancusi's studio with Marcel Duchamp; he also met Man Ray and went along to the latter's first Paris exhibition at the Galerie Six (Mesens 1979: 12). Mesens later described Satie as "a sort of anarchist" and Mesens' own tastes were more for Dada irreverence and revolt, than for early surrealism (Geurts-Krauss 33)." Neil Matheson

Mesens and Magritte, also contributed to the final issue of Picabia's Dada review 391 (October 1924). Then in March 1925 they launched a new Dadaist review Osophage. According to Neil Matheson: "The review, with its device Hop-là, Hop-là, was in a distinctly Dadaist spirit, its contributors including Arp, Ernst, Picabia, Schwitters, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Pierre de Massot and the Dutch Dadaist I.K. Bonset (Theo van Doesburg). Launched in typical Dada style, at Tzara's request the review included the last-minute addition of an inflammatory open letter "of a rare violence", relating to the latter's running dispute with André Germain, and which Tzara promised would "launch your review with a ringing scandal." (Massonet 83)"

The following year saw the launch of a new review, Marie - Journal Bimensuel pour la Belle Jeunesse, with its playful, subversive tone, typographic play and choice of contributors, was firmly in the Dadaist tradition. With Paul Nougé, who famously "vomitted Dada" Mesens and Magritte joined with Correspondance group towards the end of 1926. Nougé assumed the leadership of the Beligian surrealist group and Mesens' role was correspondingly reduced. Soon the Dada influence was replaced by that of Parisian surrealism.

Below is an article about Dada mostly from Wiki:

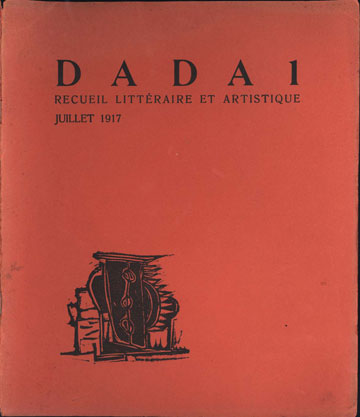

Cover of the first edition of the publication Dada by Tristan Tzara; Zürich, 1917.

Dada or Dadaism is a cultural movement that began in Zürich, Switzerland, during World War I and peaked from 1916 to 1922. [1] The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature—poetry, art manifestoes, art theory—theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works. Dada activities included public gatherings, demonstrations, and publication of art/literary journals; passionate coverage of art, politics, and culture were topics often discussed in a variety of media. The movement influenced later styles like the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including surrealism, Nouveau Réalisme, pop art, Fluxus and punk rock.

"Dada is the groundwork to abstract art and sound poetry, a starting point for performance art, a prelude to postmodernism, an influence on pop art, a celebration of antiart to be later embraced for anarcho-political uses in the 1960s and the movement that lay the foundation for Surrealism." —Marc Lowenthal, translator's introduction to Francis Picabia's I Am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry, Prose, And Provocation

Overview

"It's too idiotic to be schizophrenic." — Carl Jung on the Dada productions.[2]

Dada was an informal international movement, with participants in Europe and North America. The beginnings of Dada correspond to the outbreak of World War I. For many participants, the movement was a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests which many Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity — in art and more broadly in society — that corresponded to the war. [3]

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919, collage of pasted papers, 90x144 cm, Staatliche Museum, Berlin.Many Dadaists believed that the 'reason' and 'logic' of bourgeois capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expression that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality. For example, George Grosz later recalled that his Dadaist art was intended as a protest "against this world of mutual destruction".[4]

According to its proponents, Dada was not art, it was "anti-art." For everything that art stood for, Dada was to represent the opposite. Where art was concerned with traditional aesthetics, Dada ignored aesthetics. If art was to appeal to sensibilities, Dada was intended to offend. Through their rejection of traditional culture and aesthetics the Dadaists hoped to destroy traditional culture and aesthetics.

As dadaist Hugo Ball expressed it, "For us, art is not an end in itself ... but it is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in."[5]

A reviewer from the American Art News stated at the time that "The Dada philosophy is the sickest, most paralyzing and most destructive thing that has ever originated from the brain of man." Art historians have described Dada as being, in large part, "in reaction to what many of these artists saw as nothing more than an insane spectacle of collective homicide."[6]

Years later, Dada artists described the movement as "a phenomenon bursting forth in the midst of the postwar economic and moral crisis, a savior, a monster, which would lay waste to everything in its path. [It was] a systematic work of destruction and demoralization...In the end it became nothing but an act of sacrilege."[6]

Footnotes

1. de Micheli, Mario(2006). Las vanguardias artísticas del siglo XX. Alianza Forma. p.135-137

2. Melzer (1976, 55).

3. Richter, Hans (1965), Dada: Art and Anti-art, Oxford Univ Press

4. Schneede, Uwe M. (1979), George Grosz, His life and work, Universe Books

5. "DADA: Cities". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved on 2008-10-19.

6. Fred S. Kleiner; Christin J. Mamiya (2006). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (12th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. pp. 754.