Hi,

This blog is not a blog! It features my translation of Magritte's chapter in the 1951 Robert Motherwell book The Dada Painters and Poets, a collection of Dada (surrealist) poets and artists. Here's a quote from Andre Breton and Paul Eluard:

“To be nothing. Of all the ways the sunflower has of loving the light, regret is the most beautiful shadow on the sundial. Crossbones, crossword puzzles, volumes and volumes of ignorance and knowledge. Where is one to begin? The fish is born from a thorn, the monkey from a walnut. The shadow of Christopher Columbus itself turns on Tierra del Fuego: it is no more difficult than the egg.”

This typifies the surreal logic and prose. Magritte himself although aligned with this illogic or random juxtaposition was a believer in rational thought. Maybe the dreamworld and subconscious was unknowable and mysterious, but he still had his own theories about art.

Later in this blog you can see how some of Magritte's ideas originate. His 1936 "egg in the cage" incident led to his basic philosophy of art: 1) there's a real object 2) there's a subconscious image of that object 3) by changing (bringing to light) what we expect to see, we are made aware of our subconscious image of that object.

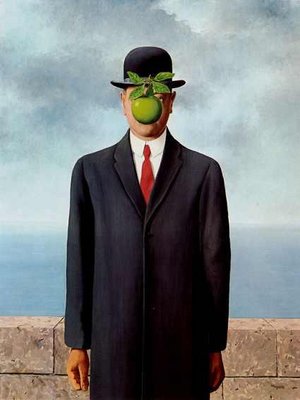

In the Son of Man 1964, below, what we expect to see has been obscured by an apple:

Son of Man- 1964

About the painting Magritte said,

"At least it hides the face partly. Well, so you have the apparent face, the apple, hiding the visible but hidden, the face of the person. It's something that happens constantly. Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present."

The Son of Man is Magitte's alter-ego, seemingly innocuous but really a Fantomas character with a touch of danger lurking under his facade. Magritte strongly identified with Fantamos in his early work and it becomes his Jungian animus, his diabolical subconscious. The Son of Man charater first appears in Magritte's 1926 “Les Rêveries d'un promeneur solitaire et Les Eaux profondes” (The Daydreams of a Solitary Walker) which dealt with his mother's suicide in 1912. In his 1926 painting Magritte's alter-ego Son of Man has turned his back on his dead mother who lies on a slab before him. The death and inferred rejection by death of his mother hardened the 13 year-old boy. Magritte disliked talking about the past and his childhood.

Here's are two of the rare interviews where Magritte discusses his childhood and early inspiration:

To prefix the 1951 publication of Magritte's analysis of his work let's look at the following similar quotes from a lecture by Magritte in 1938:

"His earliest recollection concerned a crate next to his cradle; it struck him as a highly mysterious object, and aroused in him that feeling of strangeness and disquiet which he would encounter again and again later in his adult life. His second recollection was connected with a captive balloon which had landed on the roof of his parents' house. The maneuvers undertaken by the men in their efforts to fetch down the enormous, empty bag, together with the leather clothing of the "aeronauts" and their earflap helmets, left him with a deep sensitivity for everything eluding immediate comprehension."

"During my childhood, I liked to play with a little girl in an abandoned old cemetery of a country town, where I spent my vacations. We used to lift up the iron gates and go down into the underground vault [passageways]. Once, after climbing back up to the light of day, I noticed an artist painting in an avenue of the cemetery, which was very picturesque with its broken columns of stone and its heaped-up leaves. He had come from the capital; his art seemed to me to be magic, and he himself endowed with powers from above. Unfortunately, I learnt later that painting bears very little direct relation to life, and that every effort to free oneself has always been derided by the public. Millet's Angelus was a scandal in his day, the painter being accused of insulting the peasants by portraying them in such a manner. People wanted to destroy Manet's Olympia, and the critics charged the painter with showing women cut into pieces, because he had depicted only the upper part of the body of a woman standing behind the bar, the lower part being hidden by the bar itself. In Courbet's day, it was generally agreed that he had very poor taste in so conspicuously displaying his false talent. I also saw that there were endless examples of this nature and that they extended over every area of thought. As regards the artists themselves, most of them gave up their freedom quite lightly, placing their art at the service of someone or something. As a rule, their concerns and their ambitions are those of any old careerist. I thus acquired a total distrust of art and artists, whether they were officially recognized or were endeavoring to become so, and I felt that I had nothing in common with this guild. I had a point of reference which held me elsewhere, namely that magic within art which I had encountered as a child."

"In 1915 I attempted to regain that position which would enable me to see the world in a different way to the one which people were seeking to impose upon me," Magritte explained. "I possessed some technical skill in the art of painting, and in my isolation I undertook experiments that were consciously different from everything that I knew in painting. I experienced the pleasure of freedom in painting the most unconventional pictures. By a strange coincidence, perhaps out of pity and probably as a joke, I was given a catalogue with illustrations from an exhibition of Futurist painting. I now had before my eyes a mighty challenge directed towards that same good sense which so bored me. It was for me the same light that I had encountered as a child whenever I emerged from the underground vaults of the old cemetery where I spent my holidays."

The Dada Painters and Poets 1951- Rene Magritte: Lifeline (Edited Excerpts)

"In 1915 when I began to paint the memory of that enchanting encounter with the painter, turned my steps in a direction having little to do with common sense. A singular fate willed that someone, probably to have fun at my expense, should send me the illustrated catalogue of an exposition of futurist paintings. As a result of that joke I came to know a new way of painting. In a state of intoxication I set about creating busy scenes of stations, festivities or cities in which the little girl bound up in my discovery of the world of painting lived out an exceptional adventure. I cannot doubt that a pure and powerful sentiment, namely eroticism, saved me from slipping to the traditional chase after formal perfection. My interest lie entirely in provoking an emotional shock."

"This painting as search for pleasure was followed next by a curious experience. Thinking it possible to possess the world I loved at my own great pleasure, once I should succeed upon fixing its essence upon canvas, I undertook to find out what it's plastic equivalents were. The result was a series of highly evocative, but abstract and inert images that were in the final analysis, interesting only to the intelligence of the eye. This experience made it possible for me to view the world of the real in the same abstract manner. Despite the shifting richness of natural detail and shade I grew able to look at a landscape as if though it were but a curtain hanging in front of me. I became skeptical of the dimension and depth of a countryside scene, of the remoteness of the line of the horizon."

"In 1925 I made up my mind to break from so passive an attitude. The decision was the outcome of an intolerable interval of contemplation I went through in a working-class Brussels beer hall: I found the door mouldings endowed with a mysterious life and I remained a long time in contact with their reality. A feeling bordering upon terror was the point of departure for a will to action upon the real, for a transformation of life itself."

"I painted pictures in which objects were represented with the appearence they have in reality, in a style objective enough to ensure their upsetting effect- which they would reveal themselves capable of provoking owing to certain means utilized- would be experience in the real world whence the object had been borrowed. This by a perfect natural transposition."

"In my picture I show objects situated where we never find them. They represented the realization of the real, if unconcious desire, existing in most people. The lizards we usually see on our houses or on our fences, I found more eloquent in a sky habitat. Turned (lathed) wooden table legs (bilboquets) lost the innocent existance ordinarily lent to them, when they appeared to dominate a forest. A woman's body floating above a city was an opportunity for me to discover some of love's secrets. I found it very instructive to show the Virgin Mary as an undressed lover. The iron bells hanging from the necks of our splendid horses, I painted to sprout like dangerous plants from the edge of a chasm."

"The creation of new objects, the transformation of known objects, the change of matter of certain other objects, the association of words with images, using ideas suggested by friends, using scenes from half-waking or dream states, were other ways of establishing a connection between consciousness and the real world. The titles of my paintings were chosen in such a way to arouse mistrust in the viewer."

"In 1936 I awoke in a room where a cage and the bird sleeping in it had been placed. A distortion of vision caused me to see an egg, instead of the bird, in the cage. I had just discovered a new and astonishing poetic secret from the shock of associating two different objects; whereas I had come to this startling revelation by switching the two objects. I came to the realization that the mind attaches certain qualities of how an object appears; there's only one "exact" tag for each object. I came to the determination that 1) there is the object 2) there is the shadowy tag of the object in my unconscious, and 3) the light which makes the unconscious object visible."