Creative critical thinking via Magritte's metaphores

Haggith Gor & Galia Zalmanson Levi

The first part of the workshop will show several creative and critical mechanisms in selected paintings of Magritte.

Then we will share our critical, feminist, analysis of his paintings trying to promote feminist consciousness through Magritte’s work touching on issues of control over women’s sexuality and bodies, & their objectification. Both of us used Magritte’s paintings in our critical pedagogy work and found him very significant. But as our critical, feminist consciousness developed, we came to relate to him with increasing ambivalence and anger.

In response we created ways to express our criticism and share it with others. We see this as a process of liberation. The process of uncovering implicit misogynist meanings or gender biases is applicable to countless products of our culture. Developing this process has empowered us as women, though it often also isolates us from society. It has reduced the gap we experience between the personal and the social-political.

We will ask you to seek and construct your own alternatives using creative mechanisms used by Magritte. In constructing a world of possibilities that incorporates critical feminist thinking each of you will use her/his personal/social-political voice.

We will end the workshop showing a short piece taken form a play directed by Shuki Asulin, a deaf creator, who has done a similar process with deaf actors at his final project at as a theatre student. And part of my computer artwork called veils.

We would like to ask every one to write down for her/him self- three dilemmas that she/he faces in her/his work in education. It may be a theoretical questions/problems, it may be practical ones. (Examples: a class that majority of children did not pass the standard test, discipline: a child that behaves in a way that interrupt the teacher, objections of teachers to change, are all children capable of high achievements? What are the boundaries of authority, what kind of authority? Authority versus authoritarian, are objections a stage in developing consciousness?

As we go along, explaining the different creative and critical mechanism according to Magritte’s paintings, we ask you to bear in mind your dilemmas and try to think how you use the suggested mechanism in dealing with it.

The Violin (A Little Of the Bandit's Soul)

The picture of a violin on the window edge: the creative/critical mechanism here is taking an object and putting it out of its natural context. The collar is not meant to be underneath a violin. It’s usual context is around a neck on top of a shirt. The violin gets a meaning of a face, a head above the collar. What does it mean? Music in the head? Musical thinking? Did the violin loose its qualities when it became a head? This is a mechanism of isolation in which we take from one object the its most valuable attribute or one quality that is essential for its existence. We pose a question: without what a violin is not a violin any longer? Without playing it or without the violinist? Without what an X is not an X? A king without a kingdom, a sand box without sand, a merchant without merchandise. It is also a mechanism of modification: we take out of an action or an object its most important, essential quality and add to it a characteristic from another place, context or an area.

Make a round of answering the question without what education is not longer education?

Change can be done in adding subtracting and re-organizing. Thesaurus re-organize the language, reorganization of language can break myth (post modernism and deconstruction)

In a social structure of a classroom reorganizing groups according to social groups, different identities, power distribution, achievements

Teachers take for granted that dividing children according to age or group achievements will advance children the most, actually it serves mostly the teachers control and the system’s, dividing children according to their peer groups will be what children would have felt more comfortable with.

Subtraction: what can I subtract so I will feel that it is missing, we take one thing from its natural place and you put it in a strange location then it becomes something different. We went to the Metropolitan Museum in NY to see the sky line of the city from the roof. On our way back we lost our way so and unintentionally we wondered into an exhibition called “The Spirit of Africa”.

So what we so there was a good example of the “violin” mechanism. Taking the “spirit of africa” out of cultural context it turns from an authentic being to an evidence of imperialism and colonialism. If we asked “spirit of Africa’ is not the spirit of africa? Perhaps without africa perhaps without the people who came from africa. Without them the representation in this exhibiton is not of the spirit of africa but rather of he conception of the ruling white majority on what they think the spirit of africa is. The exhibition tells me more about the observer eye then about the subject and thus it turn it to an object. What the observer or the curator see is the objectification of the “spirit of africa”. We found it to be a bit ironic. We thought that the spirit of africa was hammered down and oppressed by the slave merchants’ by land lords. Maybe it was the spirit of africa that enable the Afro american endure all the suffering inflicted upon them. So I expected, since the exhibition is taking place in NY, to learn about what happened to the spirit of africa in when it met the united states. What we found was a collection of arts objects, out of african social context, implanted into context of western art discourse. As such it appears as an imperialists representation of condescending western eye looking at africa in folklorist manner.

We do an estrangement (the smile of the cat in Alice in wonderland)

The violin is also a metaphor of a woman’s body. If a violin without the violinist to play is not a violin anymore what does it mean to us with the metaphor of the violin and woman’s body? ( a woman without a man to play/take her is not a woman)

Without what a disruptive child is not a disruptive child? Without the teacher, without the strict code of rules, without the inadequate books, without the negative treatment he/she gets. The question “without what X is not an X changes the psychological look at the child (he has problems’ therapy, lets give him Ritalin, to a social look: he needs another kind of interaction, another learning environment, he is the victim of an unequal system.

Without what school is not a school? Without what a teacher is not a teacher?

In Israel a school cannot be a school without walls, you cannot get an official recognition status from the ministry of education for a school without the structure, the physical building. In galia’s program (that belong al too the ministry of education) there are certificates and activities, studies of all kind but it happens in an informal settings, places with flexibility of time so it is not considered a school.

Who is doing the action of taking I out of context? This determines colonialization. If the white curators is taking our of context the “spirit of Africa” and interprets it as a collection of artifacts, it becomes an act of colonialization.

Without a woman is not a woman?

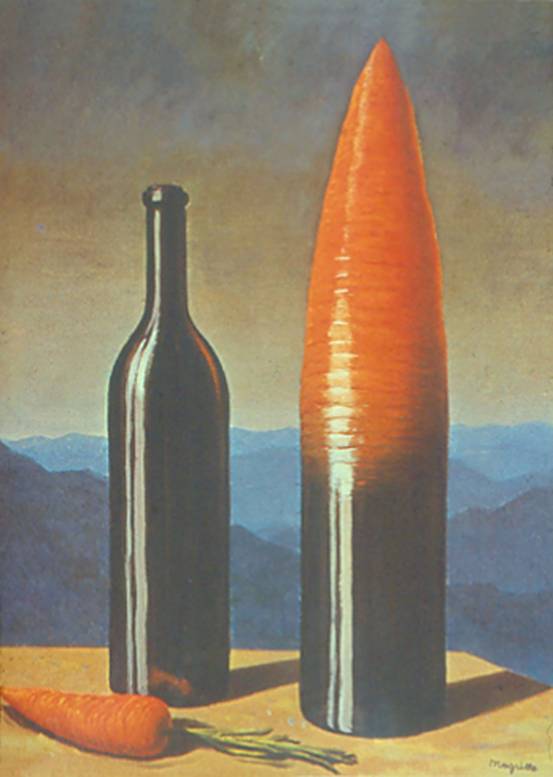

"The explanation” (carrot and a bottle)

Hybridization mechanism

Merging of two objects that are not related to each other. Adding association of two different areas.

The merge gives a new strong meaning to the two different objects. In Israel an anti cigarette campaign makes a merge of cigarette and a warm, the Berninini sculpture of Daphne merged into a tree.

Main question: what is impossible to do? We will do it. What kind of population have no connection between them, two different subjects, two personnel that don’t go along with each other it allow a creative situation to come out of an impossible one.

This mechanism can be also very harmful: for example the “melting pot” (both the US and Israel) The bottle is not a bottle it is closed at the top the carrot is not eatable anymore.

For example: there are certain subjects in school that don’t usually go together such as physical education and math, history and music,

Integration in education (Israel US)

Teacher and student the role of the teacher and the role of the student in one create a person that learn and teaches herself, at the same time.

Sometimes teachers, who work for many years in school, become hybridized with school. They identify so much with the institute that you cannot tell the two apart.

Man and woman role in one (Magritte does this hybridization) breaking the false dichotomy

Domain of Arnhiem County (Eagle Mountain)

Symbiosis of an eagle and mountain, each one gets the identity of the other. They maintain relationship of total dependency. Double imagery, the mountain looks like an eagle and the eagle looks like a mountain.

This mechanism may describe “occupation” as seen in the eyes of the occupier.

This painting feels fascist because of the images chosen, eagle and rock, and because both images are one entity. It rings the bells of Mussolini’s saying ‘I am the nation and the nation is me”. When human identity and the nation identity becomes one entity we get fascism.

In Israel the myth of Troompeldor, a hero who legendary said before he died at one of the battles fought with Arabs: “It is good to die for our country”

The notion of radical feminism “the personal is the political” is an positive example of the very same mechanism.

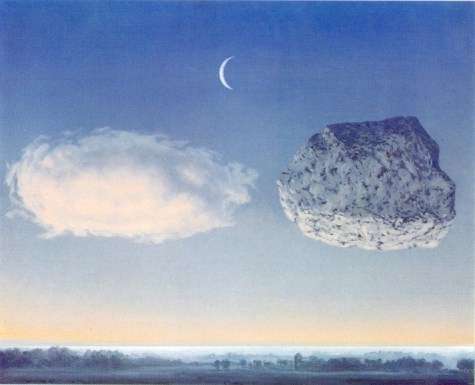

The Argonne Battle (rock and a cloud)

A rock and a cloud hanging in the sky under the “blessing” of the moon is a provocation of two different objects that are usually far and detached from each other. Meeting of unrelated objects and enabling an encounter of such objects leads to creative ideas.

It is a kind of provocation, if a cloud and a rock can meet in the sky, who can’t (yasar arafat and rabin, saadt and begin,)

A tree and a fish in the sea.

A lion and bicycle in the city,

School in a shopping mall, school in a football stadium. School at night, school in a factory, in the park.

A meeting between Olive (form Popie) and the woman for equal rights organization, Cinderella and a lawyer or children rights activist.

The rock came to the sky to meet with the cloud,

Meeting of rich upper class with the poor, lower class (the prince and the popper)

The Daughter of Pharos and Yocheved, Moses mother, a partnership of upper class lower class, royalty and slave, educated and non educated, in order to save life.

Encounter of concepts not just people:

For example: high expectation and marginalized children.

Etgarim: high prestigious sport (diving, ski, rope activities, etc) with handicapped children.

Leadership training for youth at risk, children who were squeezed out of the formal schooling system.

What does the rock says to the cloud (talking bubbles)

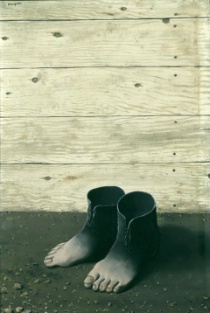

The red model (shoe and foot)

Expansion of the foot, an organic merge of the foot and the shoe, the foot is expanded to the shoe so it seems that the shoe is already part of the foot. Telescope and an eye, hand and a glove, cupboard and cloth, telephone and an ear.

Women and cloth:

Cloth and make up are often perceived as cultural expansion of women, sometimes to a point where they become women representation. Signifiers of class and gender become the expansion of the person they present. When you ask kindergarten children what is the difference between a boy and a girl, they say long hair, dress ribbons, etc.

Lower middle class codes in college: orit, a smart student, was labeled by me because her code was low,

The story of orit codes of dress demonstrate how the physical signifiers become part of a person, and how he/she are judged.

A child enters school at first grade, the teacher put on her/him same expectation she had of her/his older brother. She expands the child into the family. Immigrant children are often seen as an expansion stereotype of their country of origin that their teacher carry in their minds. (poor, uneducated, lower culture) The roles of home maintaining are considered as part of the woman, you are a woman you cook, you take care of the children. Defining a woman through motherhood (in Israel peace movement it is an ongoing debate- 4 mothers movement to get out us of Lebanon.(

Magritte uses this technique also to paint a picture of dress and breast and cunt.

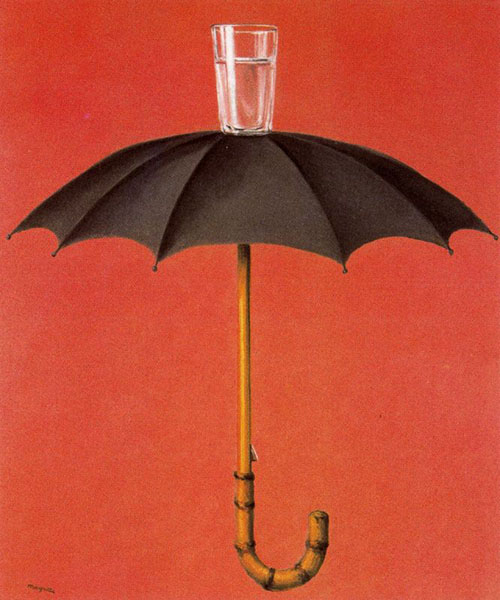

Hegel’s holiday

Hegel’s holiday

A glass of water on top of an umbrella, two objects with contradicted functions.

This mechanism based on paradox. The umbrella dispersed the water, the glass accumulate the water, the umbrella is meant to protect you from the water and here there is a glass of water on top of it. Another paradox is the juxtaposition of the name. Hegel was a philosopher that was stereotyped as a person who would not waist a time on a holiday. Hegel’s Holiday is already a pradox. In this case the paining is a visualization of the title, the title is a verbal amplifier of the visual images.

Soap that makes everything dirty, eating a plate, eraser that you write with,

I got out of the staff meeting to say what I want to say, men’ s club for women, a meeting that no one come to, a speech to an empty hall. This mechanism has humor in it,

A teacher that screams to get silent, I love you but… paradoxes can be positive

Instead of getting angry to laugh, instead of yelling whispering,

If you heat another time I will slap you.

Kindergarten for parents.

We learn to live with many paradoxes some we don’t even see.

For example the marginalized groups that are unseen by us are also the one that when we notice them are stereotyped and demonized in our society.

The war of Galilee Peace, Lebanon war (what name you used was a political statement)

This is not a pipe not a pipe,

If in some other paintings the text enrich and enforce the image of the painted picture, here it deconstructs it.

Naming (Chomsky, Friere) is a very powerful act, it is an act of giving meaning to the world, it is an act of control and regaining power.

When you say this is not a pipe it means it is not a real pipe it is an image of a pipe, but it can mean it is not an image of a pipe either it is something else, what is it? You have to think about it in different concepts. What does it symbolizes? What are the hidden meanings? What escapes our eye what is missing? What is not is as important question as what is. We want to teach teacher to ask what is not in the picture? What is missing gives us as much information as what exists.

The painting also designate the impossibility of translation from one language to the other (words to painted image in this case) It points out to the things that cannot be translated from language to language from media to media, between the visual and the word, music to painting, video to singing etc,

Try to explain voice to a deaf person, colors to a blind person it will point mostly to our blindness to our deafness. (The examples of Martha’s Vineyard and anthropologist on marc stories of Oliver Sacks)

The denial of problems (once women were equal now it is ok nothing stops them, eastern and western Jews, once it was a problem, now everybody marries everybody and you don’t know who is who.

The personal values (comb on the bed)

A room with walls that are sky, (in is out and out is in) There is an un proportional comb on the bed, a huge shaving brush on top of a cupboard, a giant soap and an enormous wine glass on the floor. In this painting the scale was transformed, the proportions changed, and objects were rearranged in terms of position and location in the room. This changes force us to see different meanings we did not notice before.

In Alice in wander land, the enlargement ridicules social structure, in guliver it is used as a means of enstrangement . Here it creates terrifying power and choking control.

The enlargement of the objects expresses strong male presence and male power. The skied walls creates unlimited space for that male presence. It gives chilling frightening feelings: with no protection solid walls the room is broken open. (the most unsafe place for women in the entire world is their own homes, there is where most women are being raped, by a person they know, it is called a “friendly rape” like “friendly fire” an oxymoron). The objects in the room are ordered in a pedant impersonal manner, a mess would have been more familiar and humane.

Using the mechanism is a lot of fun: a big scissors run after Shimshon to cut his hair, a big baby feeding his parent, a small teacher in front of a classroom etc.

How we can use it:

Changing the proportion between recess and lessons, 50 minutes break time and 10 minutes lesson time.

A child is misbehaving, teacher thinks he/she have a discipline problem, let her think about the same behavior on the beach, would it still be a discipline problem?

Group of children who curse a lot: cursing competition, what group make the longest list, replacing the cursing words with other words (avocado)

Giving a lot of homework everyday, or not giving at all.

In relation to these changes we have to ask who benefits from them, who has interest that those changes will materialize.

Galia’s program for youth at risk , (squeezed out children) is constructed with changing of times (learning is happening on varied hours of the day, and varied periods of the year) place (learning take place in community centers, children homes, coffee shop etc) the belief in children ability (as opposed to the schools which squeezed them out).

Rewriting the story of Cinderella in different locations, in space, in NY, in the jungle, rewriting Cinderella with enlarging major elements, the injustice done to her, her disobedience.

Taking the standardized exams, grades, rewards and/or punishments and installing them into adults lives. Taking love and affection given in family settings and transfer it to school.

Dislocation of concepts: when we take the slogan “it is good to die for your country” and put it into English it sounds funny and ridicules.

Holidays, (Hanukah for example) examine a holiday in today’s values, Macabees war is taught in heroic concepts, when we take it to the understandings we have on wars in our lives, we may discuss also the people who got killed, the mourning and devastation of the war. (lag ba’omer) religion and states relationship, political analysis of the time.

The personal values seems to us and to many women we talked to, like a rape. So we started looking at magritte’s paintings with our critical feminist eye:

The hybridization of a fish and a cigar,

the cigar is phallic but it becomes very interesting when we juxtapose it with the picture of the fish and a woman.

This is the reverse myth of the mermaid. it is a gender myth that introduce into the life of woman a great impossibility (you are desired and wanted by the prince when you are beautiful and un attainable, in the moment you choose to become humane, flesh and blood you are not longer wanted by the prince) here the bottom of the body is of a women, it includes her genitals, and her head is the fish. This way she is an obvious sexual object, her face is not important, her personality doesn’t exist, just her sexuality’ she has the worth of a dead fish. Most women we talked to found this image very repulsive and insulting.

We may take this painting of course, and psycho-analyze it. Magritte lost his mother when he was 13. She committed suicide by drowning herself in the river. The child must have felt deserted, he might have felt anger and helplessness that my express itself in the hatred portrayed toward women in his paintings.

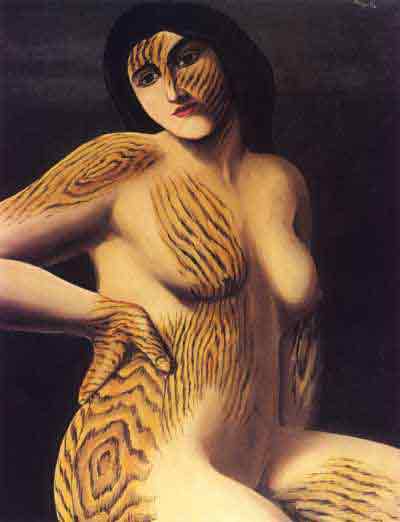

Woman and wood

Here the woman gets the qualities of an object, wood. Or the stripes of a lepard, either way she is not human.

We don’t have to rent pornographic films in order to find images of sexuality, dehumanization of women and representations of violence against women. It is deeply planted into the cultural cannon of our society.

Magritte’s paintings are pornographic and violent toward women.

Pornography is gender specific genre that is produced primary for and by men but focus obsessively on the female figure. Late works of known feminist such as Andrea Dworkin and Kathreen McKinnon, changed the definition of pornography away from obscenity terms usually refer to the influence on the male reader/observer, to a dehumanization referred to the objectification of women.

The “what” of pornography is not sex but power and violence, the “who” of pornography are women not male observer.

Pornography is an infringement of women’s freedom, pornography is the theory and rape is the practice.

When dealing with body politics and sexuality representation it is important to look at the surrealists in general and at Magritte in particular.

Women are fetishized in his paintings as “tits” and “cunt” (tits growing out of a nightgown, woman in bottle) Magritte produce a lot of representation of women “bits and pieces”.

The rape (le viole)

This is one of the most shocking painting, it turns the woman face, (face represent character and individuality) to a sexual body (objectified and general). This way he suggests that the anatomy of a woman is bound to be her destiny. It also implies that she is “sightless and senseless and dumb”.

The psychological explanation of the absent phallus in his absent faced, hollow men.