Paris: The Heart of Surrealism

From Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

André Breton marked his definitive break with Dada with the release of his Manifeste du surrealisme; Poisson soluble in 1924. This treatise established Breton's position as the leader of Surrealism[29] and earned him the support of many who had previously participated in the Paris Dada group. Aragon, Éluard, and the writers René Crevel and Philippe Soupault were among those who aligned themselves with Breton's new movement. In his Manifeste du surrealisme, Breton officially renounced Dada and gave a formal definition for Surrealism:

SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.

ENCYCLOPEDIA. Philosophy. Surrealism is based in the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected association, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life.[30]

With the release of Breton's Manifeste du surrealisme, Surrealism had a name, a leader, and a direction.

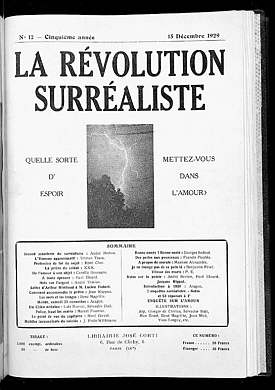

Like Dada, the Surrealist program was marked by pessimism, defiance, and a desire for revolution. Under Breton's leadership, however, Surrealism sought productive, rather than anarchic, responses to the group's convictions. Exploring the subconscious, dream interpretation, and automatic writing were just some of the the Surrealists' interests. Not only did such experiments appeal to their revolutionary spirit, but they proved to be remarkable sources of artistic inspiration. Much like Dada, the history of the Surrealist movement can be traced through its many journals and reviews. On December 1, 1924, shortly after he published the first Surrealist manifesto, Breton released the inaugural issue of La Révolution surréaliste (Surrealist Revolution).[31] The cover announces the revolutionary agenda of the journal: "It is necessary to start work on a new declaration of the rights of man." With writers Pierre Naville and Benjamin Péret as its first directors, La Révolution surréaliste set out to explore a range of subversive issues related to the darker sides of man's psyche with features focused on suicide, death, and violence. Modeled after the static format of the conservative scientific review La Nature, the surrealist periodical took a pseudo-scientific approach to such themes: it published an impartial survey on suicide and detached descriptions of violent crime data taken from police reports. The sober and uninspired format was deceiving, and much to the delight of the Surrealist group, La Révolution surréaliste was consistently and incessantly scandalous and revolutionary. Although the focus was on writing, with most pages filled by tightly packed columns of text, the review occasionally made room for a few mediocre reproductions of art, among them works by de Chirico, Ernst, André Masson and Man Ray.

The third issue of La Révolution surréaliste (April 1925), bearing the words "End of the Christian Era" on the cover, strikes a decidedly blasphemous and anticlerical tone with an open letter written to the pope by the writer and actor Antonin Artaud. His "Address to the Pope" expresses the Surrealists' revolt against what they viewed as constraining religious values: "The world is the soul's abyss, warped Pope, Pope foreign to the soul. Let us swim in our own bodies, leave our souls within our souls; we have no need of your knife-blade of enlightenment."[32] Anticlerical remarks such as this are found throughout La Révolution surréaliste and speak of the Surrealists' relentless campaign against oppression and bourgeois morality.

In the fourth issue, André Breton announced that he was taking over La Révolution surréaliste. Concerned by some disruptive factions that had developed within the Surrealist group, Breton used this issue to assert his power and restate the principles of Surrealism as he saw them. With each succeeding issue, La Révolution surréaliste became political, with articles and declarations that have a pro-Communist slant.

In the eighth issue (December 1926), Éluard revealed the Surrealists' growing fascination with sexual perversion in a piece celebrating the writings of the Marquis de Sade, a man who spent much of his life in prison for his deviant writings about sexual cruelty. According to Éluard, the Marquis "wished to give back to civilized man the strength of his primitive instincts." Breton, Man Ray, and Salvador Dalí as well were among those whose writing and imagery exhibited the influence of Sade.

While Surrealist-inspired writings often were the focus of the journal, issue 9–10 of La Révolution surréaliste (October 1927) introduces a significant development in Surrealist imagery, with the first publication of the Exquisite Corpse (Le Cadavre exquis)—a game greatly enjoyed by the Surrealists that involved folding a sheet of paper so that several people could contribute to the drawing of a figure without seeing the preceding portions. Some of the best results of this game were published in this issue.

The eleventh issue further explores the Surrealists' interest in sex with the publication of the group's "Research into Sexuality," an account of a debate that had taken place during two evenings in January 1928. In this rather frank discussion, the Surrealists had very openly expressed their opinions on several matters related to sex, including a wide range of perversions. The comments of the more than a dozen Surrealist artists and writers who participated were printed in this issue.

La Révolution surréaliste 12, ed. André Breton (Paris, December 15, 1929), cover.

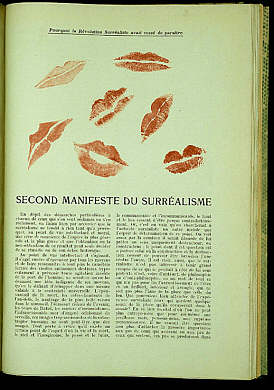

La Révolution surréaliste 12, ed. André Breton (Paris, December 15, 1929), p. 1.

In the twelfth and final issue of La Révolution surréaliste (December 15, 1929), Breton published the "Second Surrealist Manifesto." This declaration marks the end of the most cohesive and focused years of Surrealism and signals the beginning of disagreement among its many members. Breton celebrated his faithful supporters and spitefully denounced those members who had defected from his circle and betrayed his doctrine.

The views of this dissident group of Surrealists found a voice in the periodical Documents. The inaugural issue, published in April 1929, includes writings by ethnographers, archaeologists, and art historians, with poets Georges Bataille and Michel Leiris emerging as the principal contributors. Employing much of the conventional graphic design and thematic focus of La Révolution surréaliste, Documents, with an editorial board made up of university professors and other scholars with academic pedigrees, presents a more academic stance. Through Documents these dissidents attempted to define their directives for the future of the movement and sought to undermine Breton's claim on Surrealism. As with so many journals of the time, however, by the end of 1930, after fifteen issues had been published, the editors turned their attentions to other projects and Documents ceased to appear.

Breton's successor to La Révolution surréaliste was the more politically engaged journal Le Surréalisme au service de la Révolution. Although this journal appeared only sporadically between 1930 and 1933, it made a lasting mark on Surrealist imagery. Like its predecessor, it sought to counter oppression of individual liberties with writing and imagery that celebrate blasphemy, sadism, and sexual expression. In this first issue, Dalí, who had just moved to Paris and joined the Surrealists in 1929, declared, "It must be stated once and for all to art critics, artists, etc., that they can expect from the new Surrealist images only deception, a bad impression and repulsion."[33] In subsequent issues, the Surrealists would make good on this promise with increasingly blasphemous and deviant writings. Horrific texts on suicide and murder, bizarre accounts of the macabre, and a series of explorations of the work of Sade are just some of the features that run alongside the journal's aggressive political assertions.

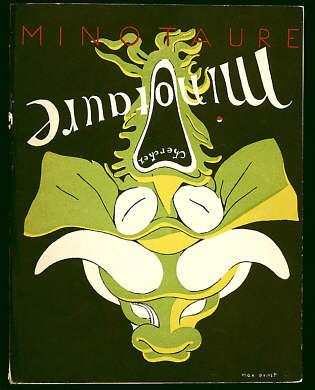

Perhaps due to the outrageous and militant tone of this journal, after only six issues sales of the journal dropped drastically and lack of financial backing forced Breton to cease publication in 1933. At this same time, the publisher Albert Skira had contacted Breton about a new journal, which he promised would be the most luxurious art and literary review the Surrealists had seen, featuring a slick format with many color illustrations. He promised that this magazine would cover all Breton's interests—poetry, philosophy, archaeology, psychoanalysis, and cinema. Skira's only restriction was that Breton would not be allowed to use the magazine to express his social and political views. Although the extravagance of Minotaure would be unlike any of the raw revolutionary periodicals conceived by the Surrealists, with Le Surréalisme faltering and his personal finances in a desperate state, Breton eventually lent his support to Skira. In the sixth and final issue of Le Surréalisme (May 1933), Breton published a full-page advertisement announcing the inaugural issue of Minotaure.[34]

In February 1933, four months before the first issue appeared, Skira had ambitious hopes for his new journal of contemporary art:

Minotaure will endeavor, of set purpose, to single out, bring together and sum up the elements which have constituted the spirit of the modern movement, in order to extend its sway and impact; and it will endeavor, by way of an attempted refocusing of an encyclopedic character, to disencumber the artistic terrain in order to restore to art in movement its universal scope.[35]

With eight hundred subscribers already in hand, in June 1933 the first two numbers of Minotaure appeared. With cover designs by Pablo Picasso and Gaston Louis Roux, respectively, these inaugural issues, expertly printed and designed, assert Minotaure's claim as the authority on the "spirit of the modern movement." A sumptuous review, Minotaure is indeed the most lavish journal in the Mary Reynolds Collection and was the most effective vehicle for promoting Surrealist imagery.

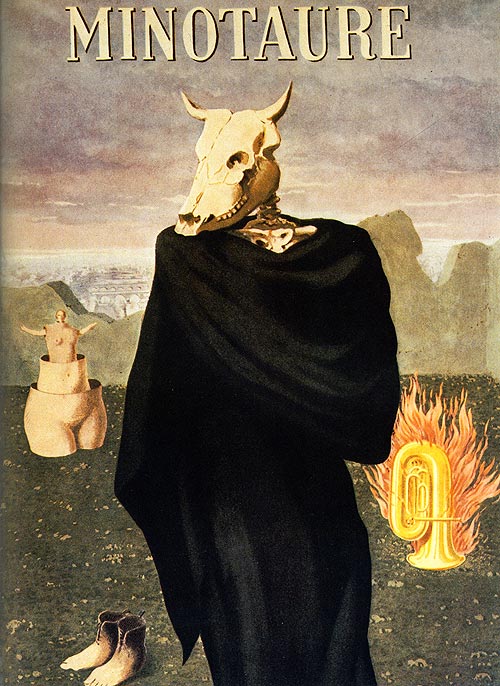

Minotaure 11, ed. Albert Skira (Paris, 1938), cover, design by Max Ernst.

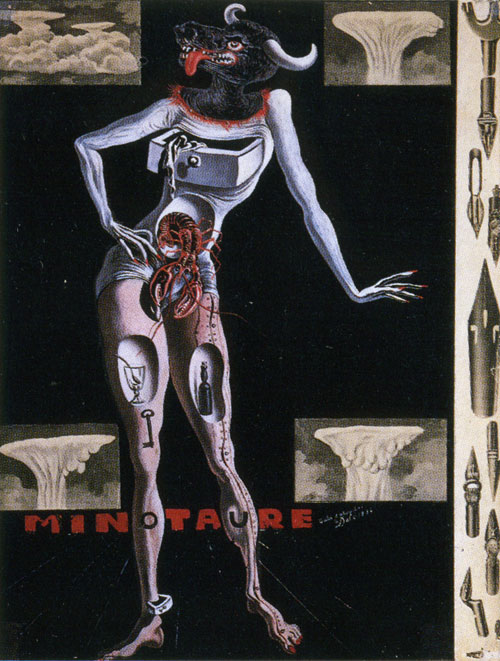

Over the next six years, twelve additional vibrant numbers were released with rich coverage not only of the Surrealists, but of many other emerging artists as well. Through Minotaure, many little-known figures such as Hans Bellmer, Victor Brauner, Paul Delvaux, Alberto Giacometti, and Roberto Matta came to the attention of the art world. With sensational covers, high-quality photography, and the frequent use of color, Minotaure brought such artists' work to life like no other magazine had. It was Minotaure that first reproduced the sculpture of Picasso, as well as some of the most provocative of Dalí's images. For Dalí, in particular, Minotaure provided a remarkable forum: his writing appears in eight issues.

Salvador Dali: Minotaure 8, ed. Albert Skira (Paris, June 1936), cover.

Magritte: Minotaure 10, ed. Albert Skira (Paris, Winter 1937), cover.

Breton, Éluard, and writer Maurice Heine were among Skira's other most valued contributors. Not only did this group offer editorial and at times fundraising assistance, they also regularly contributed features to Minotaure. Breton's theoretical writings, Éluard's poetry, and Heine's articles about book illustration and the works of Sade all added to its eclectic and animated contents.

In addition to broad coverage of visual art, poetry, and cinema, Minotaure reported on new technologies and advances in the human sciences. As Skira had so ambitiously intended, for a brief time, Minotaure was indeed a remarkable barometer of contemporary developments in all cultural activities. Although not exclusively Surrealist in orientation, it was faithful to the Surrealist spirit, and, with its appeal to the mainstream art public, gained wider recognition for the movement. By 1939, however, with Europe in a deep economic slump and on the verge of World War II, Skira was no longer able to afford to continue his deluxe magazine. In February 1939, the final issue appeared.