Surrealism in the Provinces. Flemish and Walloon identity in the Interwar Period

Author: An Paenhuysen

Published: November 2005

Abstract (E): The historical avant-garde is mostly described as a phenomenon of the metropolis, the paradigmatic place of the modern where the creation of new environments replaced the old. Avant-gardism is also seen as radically transnational and thus understood as a denial of the nation. Flemish and Walloon surrealism contradict both statements. The surrealist group of Hainaut had a provincial origin and Achille Chavée, the key figure of this group, was a Walloon nationalist. Flemish surrealist art, promoted in the magazine Variétés, was influenced by the discourse of Flemish nationalism and was incorporated in a retrograde search for a specific Nordic or Flemish sensibility, associated with a rural, provincial Flanders . This article examines the ways in which national identification and national context affected the surrealist project and contributed to variations in surrealism.

Traditionally, a historical scholarship on avant-gardism tends to explore the rhetoric of avant-gardist icons beyond singular frameworks of national and cultural contexts. It is not surprising then that general outlines on the subject are plagued by exclusively focussing on two characteristics. Firstly, the historical avant-garde is described as a phenomenon of the metropolis, the paradigmatic place of the modern where the creation of new environments substituted the old. Secondly, avant-gardism is seen as radically transnational and is thus understood as a denial of the nation. Qualifications are in order, however. For instance, Achille Chavée, the key figure of Walloon surrealism, seems to contradict both paradigms. In a 1937 letter to his Belgian comrades, he marvelled at the exceptionally provincial origin of Rupture, the surrealist group of Hainault. Rupture, indeed, was founded in 1934 in the small Walloon town of La Louvière. In 1955, at the Walloon Cultural Conference, Chavée defined Belgian surrealism as a typically Walloon phenomenon, labelling simultaneously the Flemish part of Belgium as 'un-surreal'. Chavée appeared to be at the same time a surrealist and a Walloon nationalist.

In Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium and contrary to Chavée's opinion, the Flemish avant-garde became interested in surrealism during the late 1920s, and it was regarded as a 'basic intuition' of the Flemish artist. This new orientation was indeed reflected in the unorthodox surrealism of the magazine Variétés, the 'fantastic' art of Frits van den Berghe and Victor Servranckx, and the mysticism of Marc Eemans. This Flemish surreal art, which repudiated the cultural and political program of the Parisian surrealism, was influenced by the discourse of Flemish nationalism. As such, it tied in with a retrograde search for the specific 'Nordic' or 'Flemish' sensibility associated with rural, provincial Flanders . While the Walloon provinces in Belgium became the scene of a progressive, surrealistic, modern worldview, the provinces of Flanders saw it as a more backward, nostalgic, imaginary surrealism. This should be ascribed to diverging senses of 'the nation'. I would like to highlight how national identity and national context affected the surrealistic project and, as a consequence, contributed to differentiations in surrealism. In doing so, I will demonstrate that, notwithstanding the utility of the existing general outlines on historical avant-gardism, a more contextual approach of avant-gardism focusing on its local and regional environments offers new opportunities to uncover the different agendas and national backgrounds of a multifaceted avant-garde.

1. Belgian surrealism

In the lecture 'What is surrealism?' given in Brussels on June 1, 1934 at a public meeting organized by the Belgian surrealists, André Breton paid tribute to his 'surrealist comrades in Belgium'. 'Magritte, Mesens, Nougé, Scutenaire and Souris,' Breton said, 'are among those whose revolutionary will - outside of all other considerations with regards to their agreement or disagreement with us on particular points - has been for us in Paris a constant reason for thinking that the surrealist project, beyond the limitations of space and time, can contribute to the efficacious reunification of all those who do not despair of the transformation and who wish this transformation to be as radical as possible.' (Breton 227) By referring to his 'surrealist comrades in Belgium ', Breton made it clear that there was no such thing as a 'Belgian surrealism'. 'Belgian surrealism' is indeed a contradictio in terminis. Surrealism was not to be captured in national frontiers. Breton did however acknowledge the complex relationship between Parisian and Brussels' surrealism. A lot of disputes and differences of opinion between Brussels and Paris had characterized the movement's development, as well as its general orientation, and this had resulted in a relatively independent Brussels surrealism. However, in Breton's opinion, this local Brussels variant did not affect the unity of the surrealist project.

One year later, in July 1935, Breton sent his notorious lecture on the conference of the Association des Ecrivains et Artistes révolutionnaires to the new Walloon surrealist group Rupture. It was meant to be an answer to a letter of Fernand Demoustier, a key figure of Rupture, in which Demoustier had asked for Breton's approval of the surrealist activities of Rupture and for a possible collaboration of Breton with his journal Mauvais Temps. 'Breton is certainly a strange man,' Demoustier wrote in 1935 to his surrealist comrade Achille Chavée, 'this way of answering, by sending a printed text, perplexes and astonishes me. Maybe he mistrusts young devotees he does not know and who appeal to him. We will see.' On the contrary, Breton's answer had to be understood as a positive sign of recognition and, during the following years, Breton would continue to further the local enterprise of the young Walloon surrealists. After the publication of the first issue of Mauvais Temps, Breton declared, in a devoting letter of November 1935, his admiration, insisting that the Walloon surrealists would express themselves more often. While planning a new international magazine in 1936, Breton still encouraged Rupture to continue the publication of their own journal. 'I think,' Paul Eluard told Demoustier, 'such local magazines like yours are very important and have to be published at any price without any collaboration of Paris or Brussels. Young ones like you have everything to gain by publishing separately and as a group. It gives their journal a new accent that we, old surrealists, appreciate enormously.'

Demoustier held Breton's judgment in high esteem, and he convinced Chavée that, with the approval of Breton, he would have the 'historical certitude'. Things worked out differently, though, and the group Rupture would almost never be mentioned anymore with regard to surrealism. To date, little attention has been paid in international research to 'local' surrealism in general and to the 'surrealist comrades of Belgium ' in particular. Of course, René Magritte has acquired an international reputation as the famous surrealist painter, but seldom is he associated within the Belgian context. Nonetheless, the strategy of the Belgian surrealists has also played a significant role in this neglect. Their aversion to the public, their distaste for success, their strategic anonymity and their refusal to publish their works did the fame of the Brussels surrealists no good. Rupture, on the other hand, only really got active in 1935 and nearly collapsed when Chavée left for Spain in 1936 in order to join he International Brigades. Only one single edition of Mauvais Temps was eventually published. In the last decade, the rare publications of the Belgian surrealists were sporadically collected or reprinted, but they were never translated.

Additionally, Belgian art history has been characterised for a long time by a regional orientation, by a focus on a Belgian expressionism which was connected with Flanders in general and the rural village Sint-Martens-Latem in particular, and by the exclusive attention for the Walloon and (francophone) Brussels variant of surrealism. In this perspective, the existence of a 'Walloon expressionism' and a 'Flemish surrealism' did not fit into the picture, as the 'temper' of the region excluded such tendencies. For the story of surrealism in Belgium , it is interesting to explore how local environments, especially on the provincial level, played a significant role in the emergence and development of the surrealist project. Although the Brussels surrealist movement could be called 'provincial' - at least according to Louis Aragon, who would have exclaimed in 1926, "Oh, c'est bien province" and, in doing so, enraged the Brussels surrealists - the capital was, in the 1920s and 1930s, metropolitan enough not to be regarded as the country. (Mariën 15-16) In the Flemish and the Walloon surrealism on the other hand, the provinces were at the forefront.

2. Walloon surrealism

On 29 March 1934, a formal meeting took place in the Café Liégois. Achille Chavée, Alfred Ludé, Marc Parfondry and André Lorent were present and the group Rupture was founded on that day. The Café Liégois was to become the headquarters of the Walloon surrealists, not an exception for an avant-garde movement. The café was, after all, a central meeting place for the historical avant-garde: in Berlin there was the Café des Westens, in Paris there was Le Dôme for the American Lost Generation and in the café Certá, the surrealists had their 'époque des sommeils'. Café Liégois was, nevertheless, not immediately the scene of vibrant metropolitan stimulations. It was a quiet, local bar in the provincial town of La Louvière in Hainault, a rural region in the French-speaking part of Belgium . When Fernand Demoustier arrived from Paris in La Louvière in 1935, he was very surprised to discover there the lively surrealist group of his friend Chavée. Already introduced to surrealism in Paris and Brussels , he had missed in those towns the warmth and the liveliness that such subversive action would provoke in the intellectual 'ice field' of his native town Mons , also situated in Hainault, where he had 'hibernated' for years. The discovery of Rupture in La Louvière , not so far from his hometown Mons , was consequently a revelation to Demoustier, whose surrealist artist name became Dumont (meaning 'from Mons'). 'It was the definitive liquidation,' Demoustier wrote, 'of my intellectual solitude.'

There was a significant political dimension lying at the origin of the Walloon surrealist avant-garde. In the late 1920s and the early 1930s, Chavée was very active in the nationalist Walloon movement which had come into being towards the end of the nineteenth century as a political 'francophone' movement in defence of the French language against the Flemish claims. Chavée belonged to the young Walloon militants who turned against their country, Belgium , and strived for federalism. In his poems, Chavée sang the praises of the Walloon provinces in a still very classical style: 'Wallonia, O land of hope / who cannot die as long as France lives.' (Vovelle 32) Chavée was a fanatic Francophile. The Walloon provinces should be attached to France because, in his opinion, they shared the same language, the same culture, the republican sympathies and the laicism. Chavée did not appreciate Flemish, the Dutch language, at all. It was, according to him, an underdeveloped cultural language. He feared, however, that the Walloon provinces would be 'Germanised'.

Even though Chavée gave up his active participation in the Walloon movement in 1932, he remained very attached to his Walloon roots. This became clear at a meeting of Le Mouvement Populaire Wallon in 1961 when Chavée stated that 'if the Walloon provinces do not defend themselves, they are going to be ruined'. Already before this, in October 1955, at the Second Cultural Walloon Conference, Chavée declared in his speech that 'surrealism in Belgium (...) is the fact of the Walloons. It seems that Flanders had not been susceptible in receiving the surrealist message'. Even the Brussels group, Chavée noticed, was constituted by E.L.T. Mesens, who was raised in Brussels by a French- and Dutch-speaking family, the Frenchman Paul Nougé, and three Walloon surrealists from Hainault, namely Magritte, Louis Scutenaire and André Souris. Indeed, both Magritte and Scutenaire sometimes referred in letters to their common native region, which was supposed to be inspiring for their surrealist project: 'The birds of the unpretentious country, the medieval buildings from which the ghosts have still not disappeared, the closed doors which proved fatal to a certain priest and of course the heaps of stones which amaze a stonecutter: against this background we can reach out to each other.' Magritte, on the other hand, criticized Chavée's statement on the Walloon Cultural Conference and the accompanying exposition 'The Walloon contribution to surrealism'. 'It is surrealism,' Magritte wrote to Chavée, 'that contributes if something is being contributed, and not the Walloon movement which only contributes to Walloon politics.'

The year that Chavée had abandoned his active Walloon engagement, 1932, was also the year of the perpetual strikes in the Walloon provinces as a consequence of the economic crisis. In the summer of 1932 mine strikes begun in Le Borinage and Le Centre in the region of Hainault. In this time of extreme social misery, the young lawyer Chavée discovered Marxism and surrealism. 'I owe you much,' Chavée later wrote to Breton, 'not to say I owe you everything.' The message of 'changing life, transforming the world' was, in these difficult circumstances, a revelation to him. In the following years, Chavée was more and more driven towards communism. Rupture was Trotskyist orientated. In 1936, the activities of Rupture already ceased. This coincides with Chavée's departure on 10 November 1936 for Spain to join the International Brigades. 'Since the departure of Chavée,' Demoustier wrote to Mesens, 'there is nothingness.'

3. The provinces

Chavée did not give up on Rupture, during his stay in Spain . He was, he wrote to his friends, becoming more and more a surrealist there. From this distant viewpoint, the question came to him of why had the provinces of Hainault produced all the surrealists and were at the same time the most revolutionary: 'Hainault, land of revolution and of poetry, land of surrealism. This has to be explained.' Later, at the Second Cultural Walloon Conference in 1955, Chavée repeated his question; 'Why is it that the land of Hainault has been an exquisite place for surrealism?' Nowhere else had surrealism appeared in the provinces. Demoustier tried to find the answer in his Dialectique du hasard au service du désir, written between September 1938 and April 1942 in the village of Casteau near Mons . The industrial regions of Hainault, known as Centre and Borinage, had been, Demoustier stated, especially a haven for the formation of a surrealist spirit among a small number of people. Driving in his car through the industrial regions of Charleroi and Liège, which were more populated and more lively than Centre and Borinage, it appeared to him that a bunch of surrealists normally should have been hidden there. But there was nothing, not even a name.

In this context, the situation of Mons and La Louvière suddenly appeared to Demoustier as 'extraordinary': 'The word is not too strong. You must have lived in the provinces and in particular in the small towns where the bourgeoisie have intellectual pretensions to measure their nothingness, and the incredible, unimaginable chance of finally meeting a man.' What was then, in Demoustier's opinion, so exceptional about Mons and La Louvière? Both were small provincial towns where the closeness of big, industrial suburbs failed to give them the 'classical aspect of big centres'. On the contrary, Charleroi and Liège, had this 'aspect' and possessed therefore a very different mentality. While no intellectual could have had even the most modest illusions on the importance of La Louvière or Mons , the intellectual of Liège and Charleroi was inclined to imagine, especially in a small country like Belgium , that he lived in one of the world centres. This arrogant mentality did, according to Demoustier, not further the best spirits. When the intellectual was of bourgeois origin, he was raised with an admiration for the traditional, local 'pontiffs of art' and would soon be proud of his own local glory. The talents of the lower middle-class or the proletarian class were almost immediately absorbed by small literary circles which proliferated in those regions. In La Louvière and Mons on the other hand, the population was too weak and the local 'pontiffs of art' were too mediocre. The intellectuals there had a solitary life, and were exclusively focused on Paris and Brussels . It was a place of meditation. (Dumont 137-145)

Additionally, Demoustier referred to the social struggles of the proletariat which had been more visible and more violent in Centre and Borinage than in other places. The strikes of 1932 had opened Chavée's eyes. The intellectual of the provinces could only obtain a surrealist spirit if he had lived in an ambiance which stimulated both his cultural and social conscience. This explained why all surrealists of Hainault had a bourgeois pedigree. Surrealism claimed a solid culture in order to find, in the cultural domain that is familiar to the surrealist, new ways to accelerate the decline of capitalist regime. (Dumont 145)

4. Flemish surrealism

While Chavée restricted 'the 'surrealist spirit' to the Walloon provinces, by contrast, the Flemish art critics wondered why only Flanders could produce, in Belgium , great artists and poets. André de Ridder, the promoter of Flemish expressionism, thought that the Walloon provinces were far less complex and divided than Flanders and produced less 'transcendental' persons. The Flemish artist, therefore, had to be loyal to all his instincts, his restlessness and his confusion. (De Ridder 20-21) Explanations were also found in the different landscape of the Walloon and the Flemish provinces. The Walloons lacked a 'cosmic' emotion due to the hilly landscape, while the horizon of Flanders was unlimited. (L'apport wallon 5) It was precisely the so-called transcendental aspect and cosmic feeling of the Flemish artist which would turn him inevitably, so it seemed, into a surrealist in the late 1920s.

In the magazine Variétés and the gallery L'Epoque the interest of the Flemish art world for surrealism was most obvious. The art critic Paul-Gustave van Hecke was the driving force behind both. The gallery L'Epoque was founded by Van Hecke in October 1927, the purpose of the gallery being the defence of the expressionist and surrealist paintings. Van Hecke let the surrealist Mesens run the business. Variétés was created in May 1928 as a fancy magazine with glossy paper. The newest fashion, cinema, photography, dance and urban news were discussed and gave Variétés a very modern and eclectic touch. Van Hecke was the director of the magazine and the editors were Albert Valentin, who had been accepted for a while in the Parisian surrealist group, the literary critic Denis Marion and, again, Mesens. Consequently, it is hardly surprising that a lot of surrealists published their texts or pictures in Variétés and that the newest surrealist publications were discussed in the magazine. In June 1929, a special publication of Variétés, called 'Surrealism in 1929' was even edited by André Breton and Louis Aragon themselves.

Variétés certainly had some features in common with surrealism because of its anti-bourgeoisie and its anti-Catholicism, its predilection for the fantastic and the irrational and its desire to shock. In particular the use of images in strange juxtapositions could be regarded as surrealist. But still, Variétés cannot be labelled as a surrealist magazine. Two tendencies characterised the art magazine. Firstly, Variétés was preoccupied with surrealism and secondly, it was an art magazine from the North, permeated by a typical Northern sensibility which differed from the Latin one. (Delsemme 129-145) Variétés was happy to quote for example the French writer Pierre Mac Orlan who had argued that Latin clarity veiled the eye, in opposition to the Flemish imaginative mysticism and went on to declare: 'I am Flemish!' Also, the gallery L'Epoque was not univocally orientated towards surrealism and mixed expressionism, and, more in particular, Flemish expressionism, with surrealism.

Van Hecke's contact with the French surrealists was not without problems. Already before the time of L'Epoque and Variétés, Van Hecke became interested in surrealism. In the mid-1920s, Van Hecke and his friend André de Ridder were involved in the expressionist art magazine and gallery Sélection, which supported especially Flemish expressionists like Gustave de Smet, Constant Permeke and Frits van den Berghe. Through Mesens, Van Hecke met René Magritte who, in 1926, made his first surrealist painting. This was the start of Van Hecke's attraction to the surrealist movement. He and De Ridder even wanted to dedicate an issue of Sélection to surrealism in 1926 and they asked Breton to write an article. Breton declined, as did the Brussels ' surrealist Camille Goemans who turned down the proposal. 'Surrealism is not a school,' he said, 'it is until now an absolute restricted group to which nobody is admitted without the consent of the surrealists themselves.' De Ridder protested against the monopolization of a 'universal phenomenon' and claimed his independency to judge surrealism and appreciate the movement, as he comprehended it. (Mariën 24) Van Hecke too refused to recognize the exclusivity: 'I despise all the dictatorships from Lenin to Mussolini - Breton included.' (Mariën 24)

De Ridder and Van Hecke finally abandoned their plan, but other so-called surrealist projects would follow - a recital of surrealist poems in the gallery - an exposition of De Chirico - both projects were protested against by the Parisian surrealists. Also in Variétés, finally, most of the surrealist texts were not written by the orthodox surrealist clan of Breton, but were produced by dissident surrealists like Tristan Tzara and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes or the excluded Phillippe Soupault and Roger Vitrac. The publication of the special surrealist issue of Variétés in 1929 was more the consequence of Mesens' intervention and to the lack of self-publication opportunities in Paris at that moment.

5. A dissident surrealism

Van Hecke, though, did not yield to the recurrent attacks of the French surrealists, but formulated an alternative and Northern variant of surrealism. Typical was the remark in Sélection in October 1924 that 'surrealism did not differ from the expressionism that we have been promoting from the start. In Variétés, Van Hecke changed the term 'expressionism' to 'fantastic art' and this art referred also to the Flemish expressionist friends. In the art criticism of De Ridder and Van Hecke the emphasis was shifted. No longer were the formal qualities of the paintings of the Flemish expressionists accentuated but, in contrast to the early 1920s, now the 'spirit' of the paintings was discussed. Even a separate 'canon' of Flemish surrealist precursors was created. Not only the Flemish Primitives but also James Ensor was associated with the 'spirit of surrealism' by Van Hecke.

The fantastic art was the result of the 'Genius of the North'. In 1924 De Ridder published in Sélection a series called 'The genius of the North'. The danger of regionalism in De Ridder's theory on the 'genius' was not far away. The 'Genius of the North' was set against the supremacy of Latinity in art and the Flemish expressionism appeared to be the ultimate manifestation of 'Northerners'. The 'Genius of the North' was expressive, young, spontaneous, instinctive, fantastic, almost barbarian, and spiritual and therefore capable of the creation of a new, modern art instead of French art which was exhausted by fossilized traditions and formal experiments. The working space of the 'Genius of the North' was rural Flanders , where an authentic and independent art, not affected by a cosmopolitan urban way of life, was possible. This art was inspired by Flemish folklore, medieval literature, mysticism and popular traditions. (De Ridder 1925)

This line in Flemish art history, elaborated by De Ridder, would finally lead to the Northern surrealism of Van Hecke. The 'Genius of the North' and Van Hecke's surrealist were one and the same person. He did not belong to any school, was loyal to the native soil and was rooted in the common people. He deliberately isolated himself from the international art world, had no doctrine but only followed his intuition and sub-consciousness. He cherished his Flemish roots going back to the mystic times of the Middle Ages.

6. Flemish and Walloon modernity

In the interwar period, the Flemish provinces were, and are still, the most urban region of Belgium . It could be assumed thus that Flemish nationalism was probably more positive towards the city and the industrialisation than the Walloon nationalism which flourished in very rural provinces. However, this was not the case. Demoustier thought of the provinces of Hainault as provincial but not as rural. On the contrary, he described the Walloon provinces as very industrial. Also, Chavée's early nationalist poems depicted the Walloon provinces with rivers, valleys and 'les terrils qui naissent de la mine, Entre les cris aigus des sirènes, des trains'. But Walloon industrial development was characterized mainly by the presence of the mining industry in the country. The rural Walloon provinces were the economic artery of the region. In Flanders , in contradiction, the contrast between the city and the country was much stronger.

Flemish nationalism can be labelled as ethnic in the sense that the national identity is set in opposition to outsiders. (Pil 42-50 and Couttenier 51-60) Such ethnic elements constitutive of Flemish cultural nationalism are Catholic religion and an anti-French attitude: both elements strengthened a conservative and ethical solicitude to preserve the proper characteristics of the people. Flemish nationalism developed in the nineteenth century when the industrialization of the Francophone Walloon provinces went ahead while, on the other hand, Flemish industrialization was insignificant. This resulted in the cult of the proper Flemish and traditional character. The evocation of a glorious past, in opposition to the economic and cultural decline of the present, the idealization of traditionalist values, the old language and the ancient customs by the Flemish cultural movement led to a generally conservative opposition to modernity and a rejection of metropolitan and industrial culture. While orthodox surrealism 'denounced the wretchedness of everyday life, the cults of family and fatherland, the necessity to work, masochistic Christianity', Flemish surrealism was destined to be dissident. (Short 5-6)

The Walloon movement came into being towards the end of the nineteenth century and in opposition to the Flemish ideals of rurality, religiosity and historicity, the Walloon movement was anti-clerical, had leftist sympathies and used industrial figures in the representation. Walloon nationalism was based on a proletarian, industrial identity. The Walloon movement also lacked the nostalgic discourse on the past. The Walloon provinces could be represented as the beacon of modernity. Also the orientation to Paris was not uncommon. Chavée could easily make the assessment at the Walloon Cultural Conference that his international, communist surrealism was typically Walloon. He could, at the same time, be a surrealist, a communist, an anti-clerical and a Walloon nationalist while in Flanders the nostalgic tendency made it difficult to accept modernization and globalization. Both concepts of 'Walloon' and 'Flemish' had a strong identifying character in the interwar period.

And while Breton failed to combine surrealist and political action, in Flanders politics and mysticism would be dangerously matched in the 1930s. In the political and economic turbulent times of the 1930s the rhetoric on the 'Genius of the North' would be adopted in the 'retour à l'ordre'. The unchanging national character and the timeless figures as archetypes of the 'Genius of the North' would finally suit perfectly the Heimatkunst which the Nazis promoted. Surrealism was then not to be spoken of anymore. Being avant-garde was not being strived for any longer. Van Hecke put his energy in the 1930s to the organisation L'art vivant which tried to revive the broken art world. Van den Berghes art work became apocalyptic and was titled 'Struggle of death' and 'Self-portrait with skull'. The communist Walloon surrealists went into hiding during the Second World War. Chavée went underground in a village near La Louvière , Demoustier fled the country to Nice and Toulouse but was terribly homesick and would finally make the fatal decision to return home. Being in Toulouse in 1940, he was thinking about his provincial hometown: ' Voici l'exil ,' he wrote,

ou la prison

Où sont ma ville et ma maison?

Peine inutile d'avoir raison

c'est la saison des imbéciles

Où sont ma ville et ma maison?

Illustrations

Achille Chavée, Simone Chavée, Mado Lorent, Georgette and Fernand Demoustier in the 1930s

(Bruxelles, Archives et Musée de la Littérature)

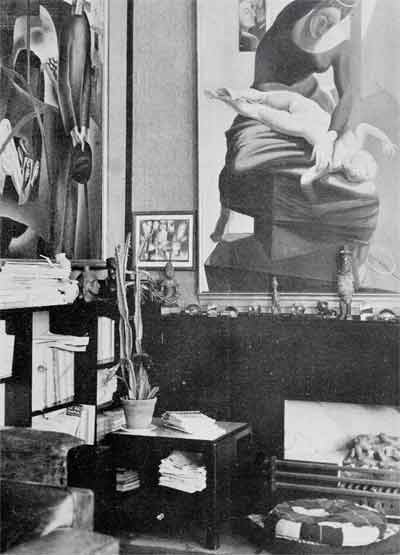

A painting of Frits van den Berghe next to ' La Vierge corrigeant l'enfant Jésus devant trois témoins' by Max Ernst in the living room of Paul-Gustave van Hecke in Brussels

References:

Ch. Béchet en V. Formery ed., 'Autour d'Achille Chavée. Je suis le grand seigneur d'une légende nue, un gemeau allaité par la reine d'amour' , tent.cat Museum Ianchelevici La Louvière, 18 December 1999 - 25 February 2000 (La Louvière 1999).

A. Breton , Oeuvres complètes , ed. Ph. Bernier, E.-A. Hubert en J. Pierre (Paris 1992)

X. Canonne, J. Mambour en Y. Vasseur ed., Le surréalisme à Mons et les amis bruxellois (1935-1955), tent.cat. Maison de la culture de la région de Mons, 7 June 1986 - 29 June 1986 (Jumet 1986)

Ph. Destatte, L'identité wallone. Essai sur l'affirmation politique de la Wallonie aux XIX et XXèmes siècles (Charleroi 1997).

R. S. Short, 'The politics of surrealism, 1920-36', Journal of Contemporary History, 1 (1966) 2, 3-25.

L. Pil, 'Painting at the service of the new nation state', K. Deprez and L. Vos eds., Nationalism in Belgium . Shifting identities, 1780-1995 ( Basingstoke 1998) 42-50.

P. Couttenier, 'National imagery in the 19 th century Flemish Literature', K. Deprez and L. Vos eds., Nationalism in Belgium. Shifting identities, 1780-1995 (Basingstoke 1998) 51-60.

A. de Ridder, Le génie du Nord (Antwerp 1925).

P. Delsemme, ' Variétés (1928-1930), une revue éclectique', R. Frickx ed., Les relations littéraires franco-belges de 1914 à 1940 (Brussels 1990) 129-145.

M. Mariën ed., Lettres surréalistes (1924-1940) (Brussels 1973).

Savoir et Beauté , special issue Surréalisme en Wallonie , 1961.

J. Vovelle, Le surréalisme en Belgique (Brussels 1972).

Archives:

Brussels , Private archive, E.L.T. Mesens.

Brussels , Archive of Contemporary Art in Belgium , Achille Chavée and Fernand Demoustier.

La Louvière, City Archive, Achille Chavée.

Los Angeles , The Getty Research Institute, E.L.T. Mesens.

Paris, Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, André Breton.

An Paenhuysen is doctoral student at the department of history at the University of Leuven, Belgium. She is currently working on a book that examines the cultural criticism of the Belgian artistic avant-garde in the interwar period. She has published on the Belgian avant-garde in several leading journals.