135 Esseghem Street, Jette (outskirts of Brussels)

By 1930 Magritte became tired of waiting for a one-man exhibition. Paris was in the midst of recession after the 1929 Great Depression. His friend Goemans was forced to close his Paris gallery and many collectors and galleries become bankrupt. Magritte no longer had a steady income and his relationship with surrealist leader Andre Breton had deteriorated. Discouraged and homesick the Magritte's returned to Brussels in July 1930.

After staying several places they rented an apartment (the ground floor and garden) at 135 Esseghem Street, in Jette (outskirts of Brussels). Rene returned to commercial work and Georgette worked in an art shop. Rene was 32 and his talent as an artist was undeniable. The Magrittes lived in Jette for over two decades until 1954 when they moved to Schaerbeek, a suburb to the east of Jette.

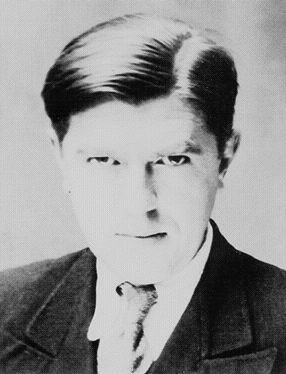

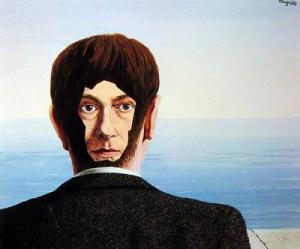

Magritte at age 32 when he moved back to Brussels

Rene Magritte made his home in Jette in order to be close to his brother, Paul, a pianist, and to his wife's family. He rented the ground-floor flat in order to have a garden for his dogs. The 135, Esseghem Street apartment was also the headquarters of the Belgian surrealists. The painter’s friends met here weekly and organized all kinds of performances. These meetings resulted into many subversive activities, books, magazines and tracts.

The years spent in Jette were among Magritte's most prolific, and artistically his most creative, even though he met with little financial success. He painted half of his 1,600 canvases in the modest dining room that doubled up as his studio. His house is now The René Magritte Museum, a house where the famous artist lived and worked for 24 years.

Studio Dongo 1931-1935

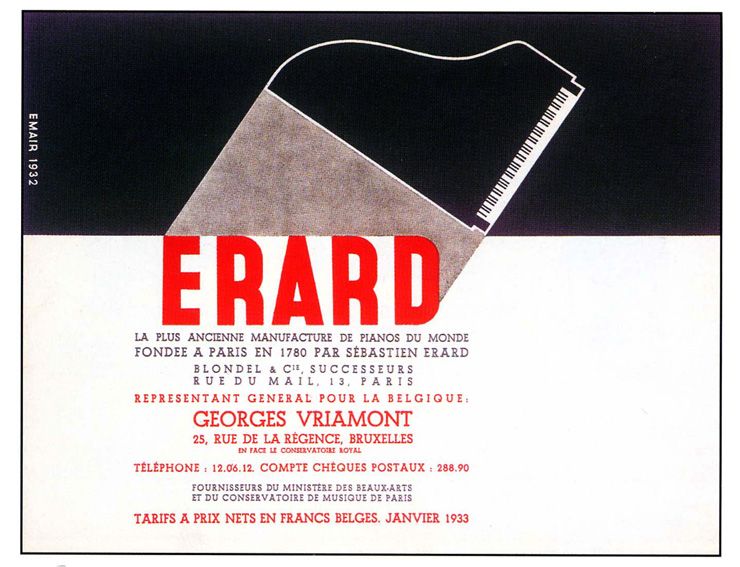

Magritte and his musician brother Paul built at the back of his garden an advertising company, Studio Dongo, named after Fabrice Del Dongo. Rene's main goal was to paint and he did ad work only because of his financial difficulty. The Studio Dongo followed the rules of advertising: their messages are neutral and simple. They produced illustrations, advertising artwork and covers for musical scores as a means of making money while Magritte continued to try and sell his paintings.

1931 Studio Dongo Ad by Magritte for Pleyel

Although Magritte exhibited twice at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in the 1930s (a one-man show of 59 works in 1933, followed by a group show with Man Ray and Yves Tanguy in 1937), he was temporarily left without a commercial outlet for his paintings after the closure of Le Centaure in 1930. The gallery’s stock of 150 recent paintings by Magritte was purchased by his old friend E. L. T. Mesens. Later that decade Mesens moved to London, where he became director of the London Gallery. Through Mesens, Magritte gained greater recognition in Great Britain.

In 1933, Magritte defined his artist intentions by stating that the primary aim of his work from that point on would be to reveal the hidden and often personal affinities between objects, rather than juxtaposing unrelated objects. He continued to remain in contact with Breton and Eluard in Paris, contributing to the final two issues of "Le Surrealisme" and remained associated with surrealism in general throughout his career.

Soon Magritte's output increased due to the sponsorship of Claude Spaak, who he met in 1931. Spaak was a playwright, but had also been an active collector of Magritte's paintings for some time. In 1935, he made a semi-formal arrangement to allow Magritte to abandon commercial work and focus fully on his own artistic output. To this end, he provided the artist a monthly stipend, while also guaranteeing the paintings he produced. In addition to this, Spaak actively sought other sponsors for Magritte.

When Edward James took over Magritte's Dongo Studio company around 1936, Magritte quit his ad work at Dongo and devoted himself entirely to painting. Thanks to James, Spaak and Mesens, Magritte’s art began to be recognized internationally. Consequently companies began to contact Magritte to create artwork for advertizements he often was inspired directly by his canvases. For example, the design used for a New York perfume company, Mem, is an elaborate version of his painting La clef des songes.

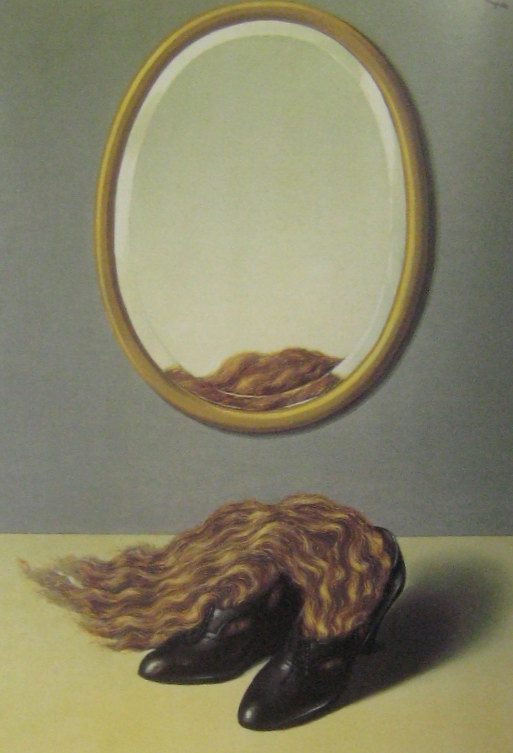

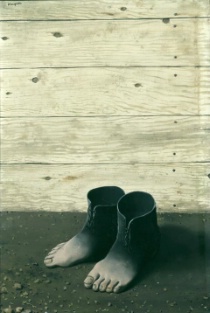

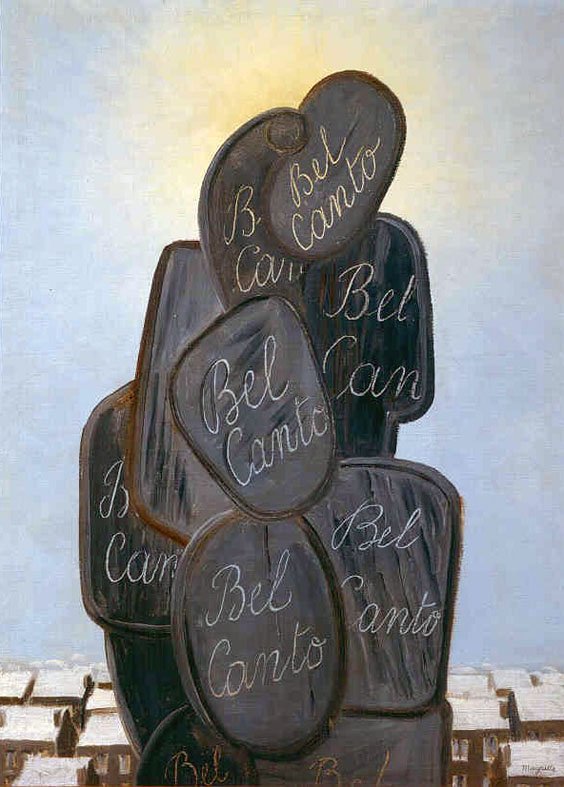

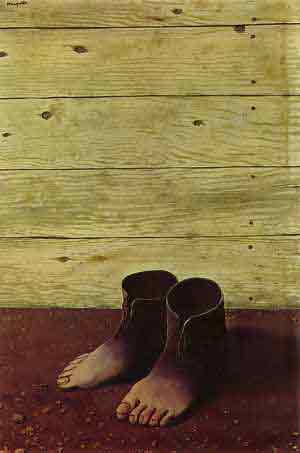

Origninally inspired by de Chirico's poetry in the combination of normally unrelated objects, Magritte preferred to examine unexpected encounters between objects already in some way associated with each other. In the winter of 1932–3, for instance, he painted a birdcage containing an enormous egg, titling it Elective Affinities (see in galery below) after Goethe’s novel Die Wahlverwandtschaften (1809). Often taking his titles from poetry, literature, films and musical scores on the completion of the picture, he invited friends, notably the writers Paul Nougé and Louis Scutenaire, to make suggestions for his titles. While the titles of his first Surrealistic paintings maintained a certain logic in relation to the imagery, from the 1930s words and images gradually acquired greater independence from each other, often retaining only an associative link. For example, he entitled a miniature reproduction in plaster of the Venus de Milo, a torso admired as the expression of feminine beauty in spite of the fact that it has no arms, the Copper Handcuffs (h. 370 mm, 1936; Paris, Charles Ratton priv. col.; see 1978–9 exh. cat., no. 200). Magritte continued to make frequent use of abstract forms, particularly in paintings that included texts, such as Bel Canto (1938; priv. col.; see Waldberg, p. 166), until the late 1930s. As a means of broadening the range of association, he sometimes represented an object undergoing metamorphosis into something else, as in the Red Model (1935; e.g. Stockholm, Mod. Mus.; Paris, Pompidou), in which the pointed toes of a pair of boots become the toes themselves. Such strategies, drawing attention to the relationship between inanimate and living objects, were similar to those employed by other Surrealists.

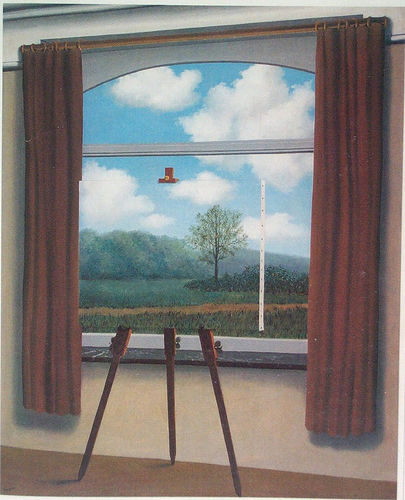

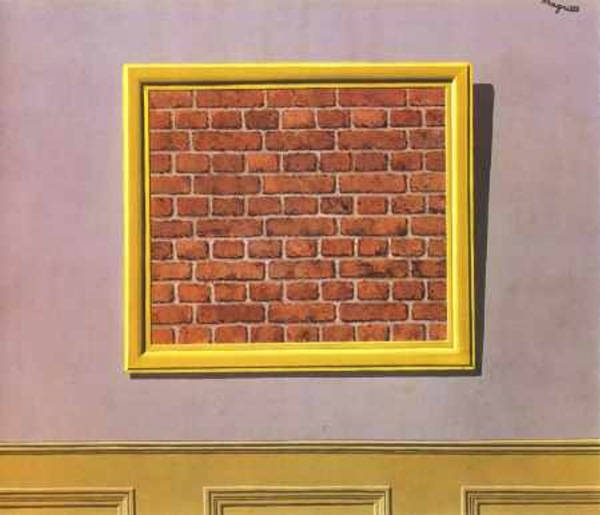

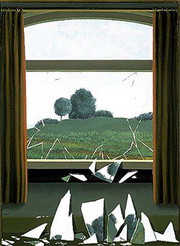

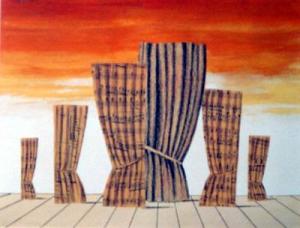

Magritte challenges the difficulty of artwork to convey meaning with a recurring motif of an easel (painting within a painting), as in his The Human Condition series (1933, 1935) and his La Belle Captive series (six paintings from 1931). He wrote to André Breton about The Human Condition that it was irrelevant if the scene behind the easel was different than what was depicted upon it, "but the main thing was to eliminate the difference between a view seen from outside and from inside a room." The windows in these pictures are framed with heavy drapes, suggesting a theatrical motif. Just as theatre reflects our lives, or ideal replications of our lives, to an audience simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar with the situation, so does Magritte's artwork.

London

Edward James was an eccentric poet, collector, and patron of both Dalí and Magritte. In 1935 James visited Salvador and Gala at their home in Catalonia. Dali was invited to London to help decorate the Monkton house in Chelsea with surreal furnishings and paintings. Through an introduction to James from Dali and others, Magritte also was consulted about the interior designs. The famous lobster telephone came from James collaborations with Dali. James remained an important supporter and collector of Magritte's work and Magritte stayed with him on several occasions in London.

Turmoil in Europe

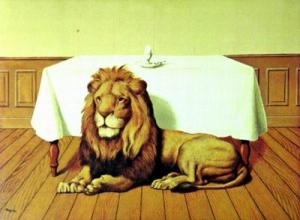

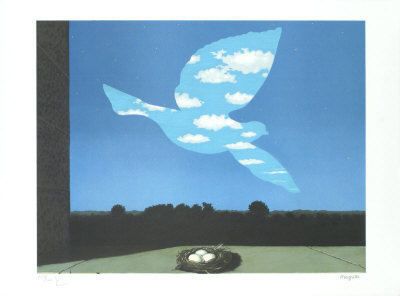

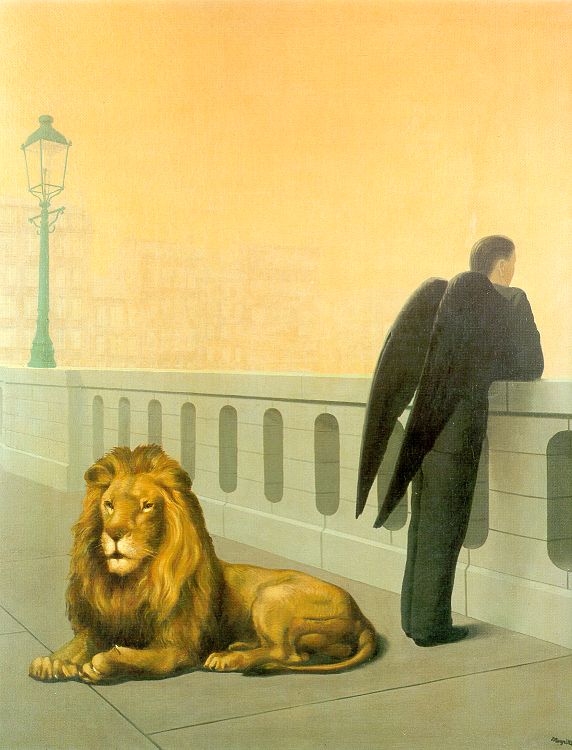

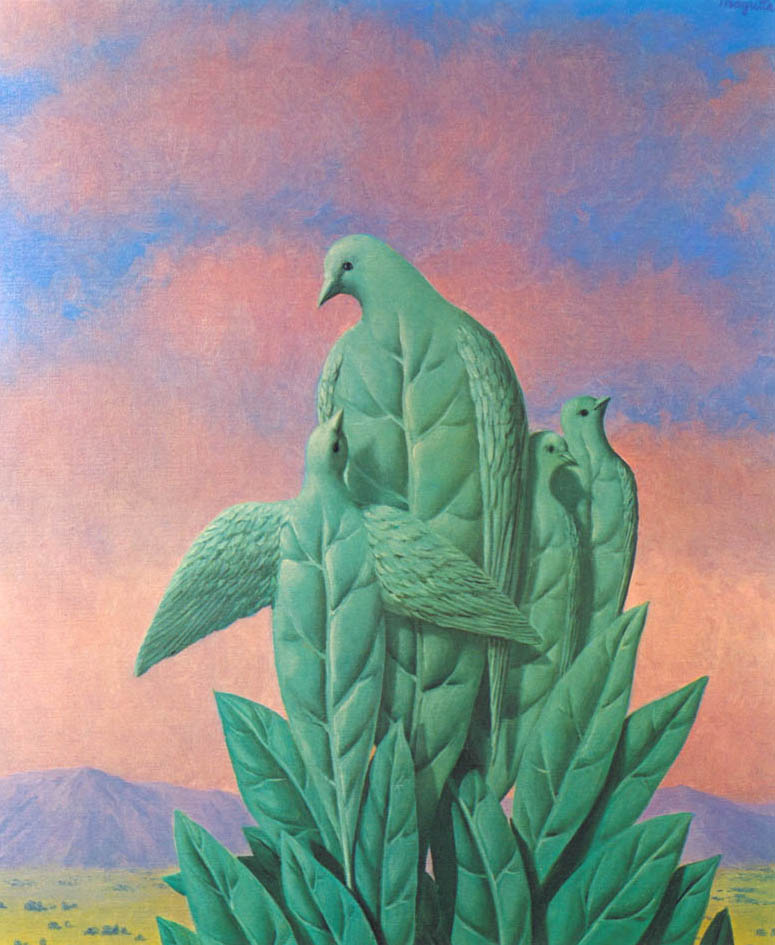

With the Nazi uprising came several paintings dealing with the upcoming World War notably Black Flag (see below) and The Witness (see below). He also created several new icons dealing with war including leaf birds and lions. Athough the war didn't officially begin until the invasion of Poland in September 1939, the German air bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War in 1935 signaled the coming terror. The Nazis would occupy Brussels from May 1940 until September 1944.

1939-1942 Marital Difficulties- World War II

On his trips to London to visit James and Mesens to prepare for his exhibitions, Rene had a relationship with the young surrealist model known as the "Surrealist Phantom" of 1936, the artist Sheila Legg, who posed for surrealist events with Dali and others. Magritte did not want to hurt Georgette or arouse her suspicions, so he arranged for his friend, Paul Colinet (1898-1957) a Belgian surrealist poet, to spend time with Georgette and keep her entertained. While Magritte was away Georgette and Paul Colinet became involved.

When the German troops invaded Belgium and Holland in May 1940, Rene Magritte fled Brussels and his marital problems for Carcassonne, France. Several of his close friends left with him but Georgette did not go. He spent three months in France before conditions allowed his return to Brussels and soon he reconciled with Georgette, his true love. Because of the German occupation and his marital problems, Magritte became depressed and experimented with different styles (beginning in 1943) perhaps to escape his emotional demons. Magritte wrote to Eluardon December 4, 1941: "My attack of exhaustion [depression] is almost over and for some time i've been enjoying working" and later he writes about his paintings, "I would exploit the bright side of life."

Magritte's Gallery 1931-1942

Below are many images Magritte's paintings (chrologically organized) from 1931. Because I do not yet have accurate information there may be a few mistakes regarding the dates. This is when Magritte's created some of his best works, especially starting the Human Condition and La Belle Captive series featuring a painting of a painting (on an easel). He would paint several versions of his favorite paintings like his Black Magic and Memory series that he started in the 1930s.

Enjoy!

%201931.jpg)

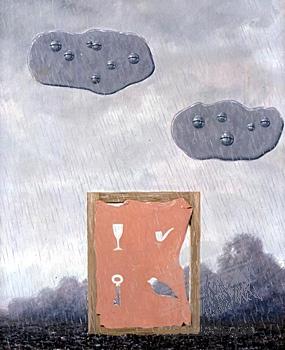

The Tempest I- 1931

The Tempest is a nice illusion: the objects inside the window appear to also be buildings or skyscrapers that are outside and have low lying clouds- or maybe they are just file cabinets and the clouds are inside the room.

The Curse (La malédiction) 1931

La malédiction is signed 'Magritte' (lower left) - oil on canvas - 21 1/2 x 29 in. (54.5 x 73.5 cm.) - Painted in 1931 - Estimate: £800,000-1,200,000 Provenance: (Probably) Claude Spaak, Brussels, by whom acquired from the artist. Emile Happé-Lorge, a gift from the above. Anonymous sale, Guillaume Campo, Antwerp, 13-15 October 1964. Private collection, Belgium, by whom acquired at the above sale. Acquired from the above by the present owner in 1973.

Literature: M. Mariën, 'La malédiction', in Le Ciel bleu, Brussels, 12 April 1945, p. 3.

D. Sylvester (ed.), René Magritte, catalogue raisonné, vol. II, Oil Paintings and Objects, 1931-1948, Antwerp, 1993, no. 337 (illustrated p. 173).

Exhibited: Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Art wallon contemporain, December 1931 - January 1932, no. 55.

Brussels, Galerie Robert Finck, Exposition de peinture belge moderne: de Jacob Smits à Roger Dudant, March 1962, no. 42 (illustrated).

Ferrara, Gallerie Civiche d'Arte Moderna, Palazzo dei Diamanti, René Magritte, June - October 1986, no. 22.

Punkaharju, Finland, Retretti Art Centre, Surrealism in Visual Arts and Film, May - October 1987.

London, The Hayward Gallery, The South Bank Centre, Magritte, May - August 1992, no. 57 (illustrated); this exhibition later travelled to New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, September - November 1992; Houston, The Menil Collection, December - February 1993 and Chicago, The Art Institute, March - May 1993.

Brussels, The Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, René Magritte, 1898-1967, March - June 1998, no. 97 (illustrated p. 116).

Notes from Christie's: A patch of sky fills the canvas in La malédiction. Magritte has restrained himself from painting any extraneous, distracting details, creating a picture that appears deliberately incomplete. Is this intended to resemble a window on the wall? Perhaps Magritte is conveying the extent to which his pictures act as windows into a dimension of infinite and subtle poetry, forcing the viewer to appreciate anew the mysteries of everyday existence to which we have become all too inured. By presenting the viewer with a portion of sky on the canvas, Magritte shows both his credentials as a Surrealist, inviting us into his unique visual world, and as an artistic innovator, flagrantly disregarding pictorial convention and bending it to his own use.

In David Sylvester's catalogue raisonné of the works of Magritte, it has been deducted that La malédiction was the painting that the Belgian Surrealist made for his friend Claude Spaak in 1931, which was exhibited in Brussels later that year. This would make it the earliest work to bear the title La malédiction: the single painting filled with the sky alone would be a theme to which Magritte returned several times over the following decades, especially in a group of small oils which he gave as gifts to his friends. This, then, reflects the fact that these works, showing the cloud-specked sky, must have been close to the artist's heart.

The picture's background as a gift for Spaak, a prominent novelist and playwright who would also become one of the greatest collectors and advocates of Magritte's works, marks this as a milestone in the Belgian Surrealist's career. For this picture dates to the period immediately after Magritte's break with the Parisian Surrealists and André Breton in particular. It was on his return from Paris that Magritte first met Spaak, who was the first Director of the Societé Auxiliaire des Expositions at the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels, where La malédiction was exhibited in the year of its execution. Magritte had broken with the Surrealists in Paris for various reasons, tensions having increased between himself and Breton, the self-appointed guru of the movement. This culminated in Magritte and his wife Georgette storming out of a Surrealist meeting when Breton questioned why Georgette was wearing a crucifix. The break seemed, at the time, final, and it is a tribute to the importance and influence that Magritte wielded already after only a few years painting 'Surreal' works that many friends attempted to mediate and heal this rift. In the end, it lasted only a few years, but even after the rapprochement, Magritte was a committed 'other', living in Belgium and following his own path, rather than what he perceived as the more prescriptive path of the Parisian Surrealists. On his return to Brussels, Magritte had encountered old friends, made new friends, moved into the house that would remain his home for over two decades, and thus began his strange and idiosyncratic assault on the hierarchies and hegemonies of the world, of our perceptions, from the deceptively unassuming vantage-point of his bourgeois home. Unlike the flamboyantly Surreal artists, thinkers and writers congregating in Paris, Magritte channelled his vision into his pictures, appearing as the calm, bowler-hatted man, almost anonymously pushing his viewers towards great revelations.

Perhaps the presence on one's walls of a canvas showing the cloudy sky was intended to imply that the viewer had already stumbled into an epiphany, somehow appearing within the disjointed universe within Magritte's paintings. In several works from the preceding years, and again in works that would punctuate the remainder of his career, Magritte had included sky-paintings within his pictures, and yet had not produced sky-paintings per se. This had begun when 'panels' of sky, strange and incongruous areas within a work's composition, appeared in pictures such as L'usage de la parole, L'idée fixe (in the Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin) and Au seuil de la liberté (Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam), all of 1928; actual paintings-within-paintings showing the sky 'framed' occurred around this time in works including La vie secrète and Le salon de Monsieur Goulden of the same year; and Magritte then appears to have chosen to paint a group of sky-pictures similar to those featuring as paintings-within-a-painting in those two works, when he created the four-panelled Les perfections célestes in 1930. In that work, as in La malédiction, there is the implication that some element from within Magritte's own universe has leapt into our dimension, has crossed the boundary of the canvas. Or, instead, that we have entered Magritte's realm.

There is a discreet absurdity to this sky-filled canvas. It lacks any frame of reference to the world that surrounds the sky: Magritte has taken what is traditionally the upper portion of a painting, perhaps a landscape, perhaps a narrative work, and has ripped it away from any other frame of signification. And yet, why should a section of the sky, as beautiful as it is, not merit the status of subject in its own right? The sky, after all, has been painted on many ceilings by many great artists. Magritte, then, has taken an art historical theme, something from the accepted canon of what is and what is not traditionally considered art, and has turned it discreetly upon its head. If seascapes and landscapes should exist as pictures, why not skyscapes? The sky is a canopy arching over us all, a great uniting bond between all the inhabitants of the Earth, and its absence from older paintings as a theme in its own right (except in occasional studies) appears an injustice. Magritte has jarred us into a better and more active appreciation of one of the everyday elements of our everyday worlds, bringing to the fore the sense of wonder that we should feel each and every day. It is on this level, far from the subconscious or hidden dimensions that were such a source of fascination to his Parisian Surrealist contemporaries, that Magritte's pictures work. Rather than revealing hidden realms, he asks us to appreciate the crazy wonders of the universe that we inhabit and to which we are all too accustomed. It is a tribute to his success in this that another friend of Magritte's, Paul Nougé, himself the owner of the second, 1936 reprisal of the theme of La malédiction, wrote in his final text on his artist friend:

'The sky. No one has yet pursued the analysis of this considerable object far enough. A human history of the sky should be written, in order to disentangle the curious, age-long mishmash of naïve impressions, stimulations and illuminations (The eternal silence...), of more or less exact physics, and of flimsy religious constructions. In this domain, painters' revelations have been rare. And banal just open any encyclopedia of painting. 'Magritte, however, is the exception' (P. Nougé. 'Les points sur les signes', 1948, from Histoire, trans. B. Wright, reproduced in S. Whitfield, Magritte, exh.cat., London, 1992, no. 57).

The View (Le Panorama) 1931

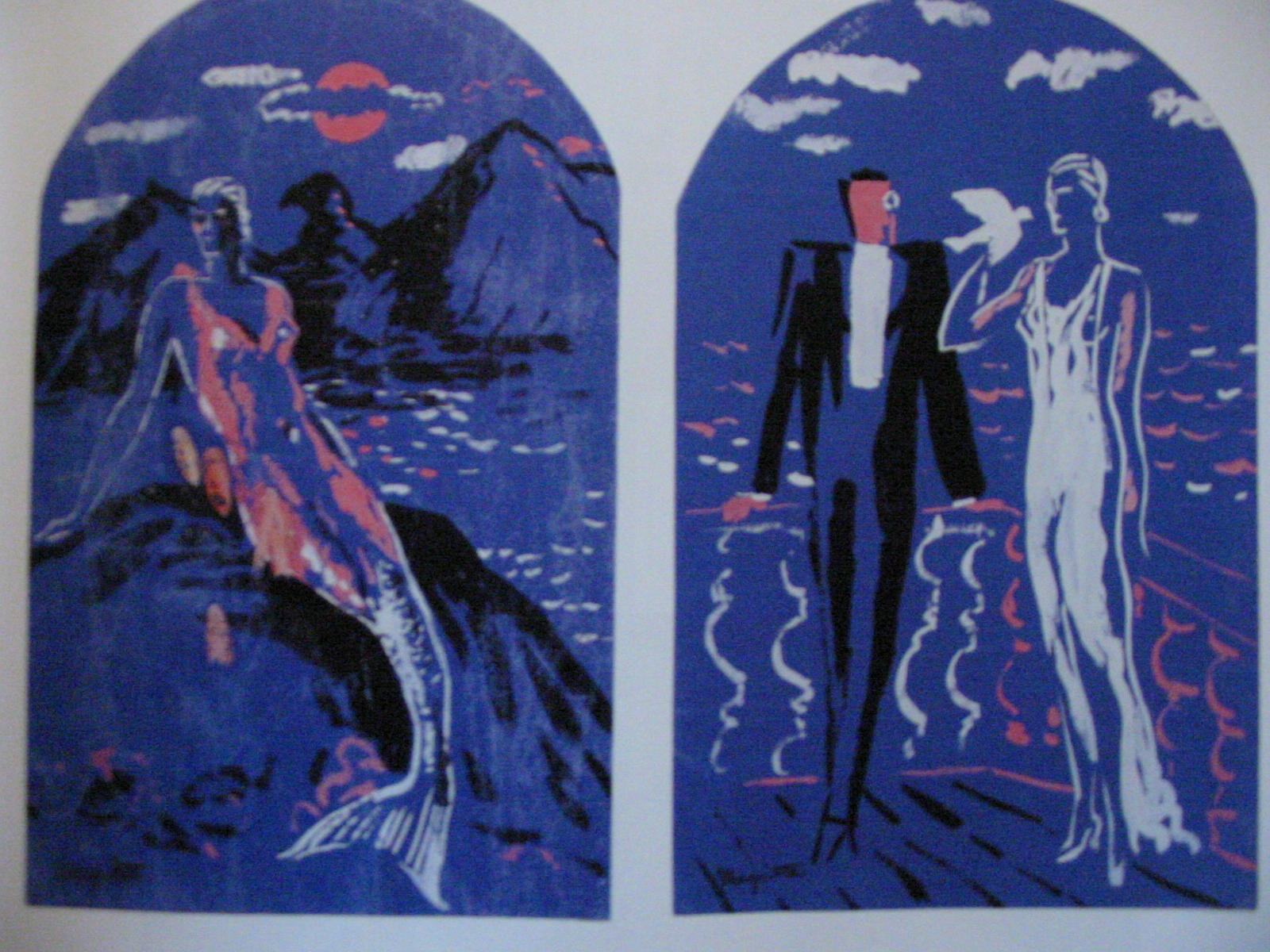

Mural design for Maison Norine 1931

The background of the left arch features an early version of the eagle-mountain found in Magritte's famous Domain of Arnheim.

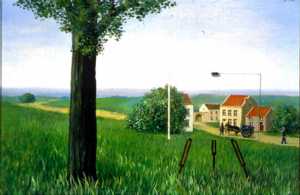

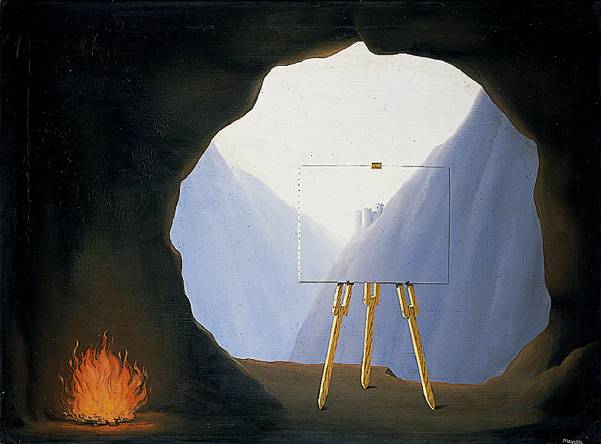

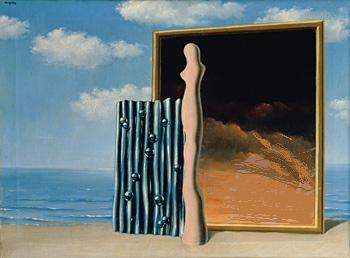

The Fair Captive (La Belle Captive)- 1931

La Belle Captive is the first of six works painted between 1931 and 1967, all of them entitled La Belle captive. There is a later lithograph done in 1962 of this painting. What characterizes the La Belle captive series of paintings is the undecidability of the image. Each one of the six canvases contains an easel that holds a painting within a painting, a procedure that establishes specular duplication with mise-en-abyme effects. The painting on the easel replicates the landscape beyond it and the internal frame breaks the continuity of the image while accentuating it. Although the background and the foreground overlap, the perspective is impossible. Is the canvas transparent or opaque? Are we looking through it at images in the distance or are these images in front of us. This ambiguity sets up a visual paradox that cannot be resolved and the undecidability of the perspective elicits epistemological and ontological concerns in the mind of the observer.

La Belle Captive- 1931 Gouche

.jpg)

La Belle Captive II (circa 1931) No date given

Magritte painted multiple versions of his popular paintings. This version seems to be an early version.

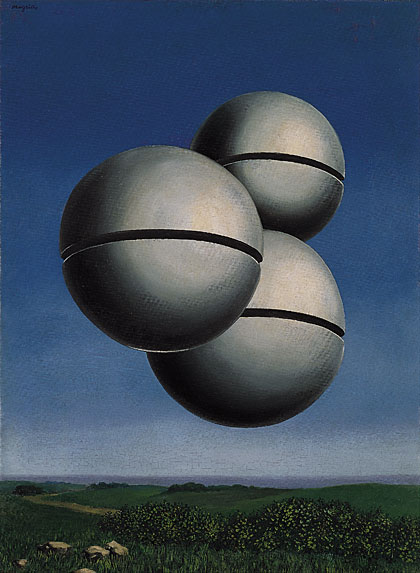

Voice of the Space (La Voix des airs), 1931. Oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 21 3/8 inches (72.7 x 54.2 cm).

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 76.2553.101. René Magritte © 2007 C. Herscovici, Brussels/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Influenced by Giorgio de Chirico, René Magritte sought to strip objects of their usual functions and meanings in order to convey an irrationally compelling image. In Voice of Space (of which three other oil versions exist), the bells float in the air; elsewhere they occupy human bodies or replace blossoms on bushes. By distorting the scale, weight, and use of an ordinary object and inserting it into a variety of unaccustomed contexts, Magritte confers on that object a fetishistic intensity. He has written of the jingle bell, a motif that recurs often in his work: “I caused the iron bells hanging from the necks of our admirable horses to sprout like dangerous plants at the edge of an abyss.” (Quoted in S. Gablik, Magritte, Greenwich, Connecticut, 1970, p. 183)

The disturbing impact of the bells presented in an unfamiliar setting is intensified by the cool academic precision with which they and their environment are painted. The dainty slice of landscape could be the backdrop of an early Renaissance painting, while the bells themselves, in their rotund and glowing monumentality, impart a mysterious resonance.

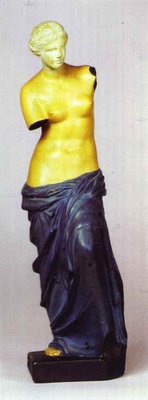

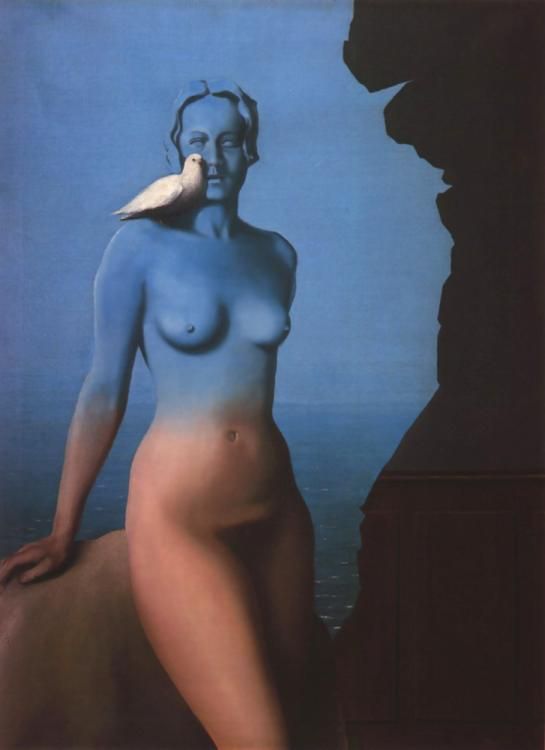

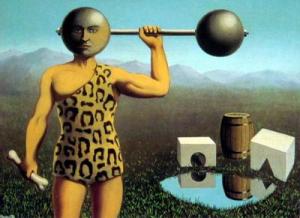

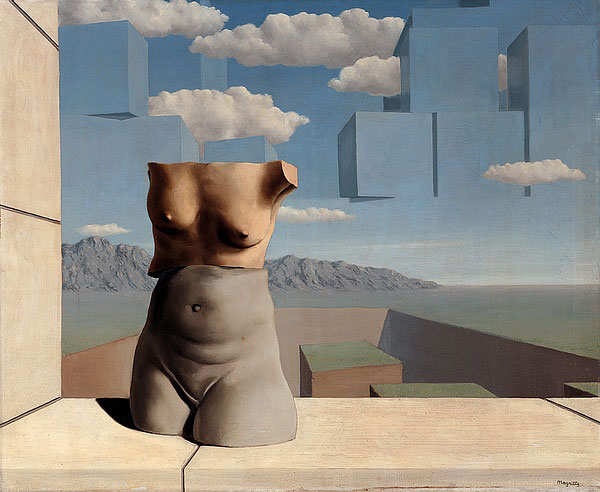

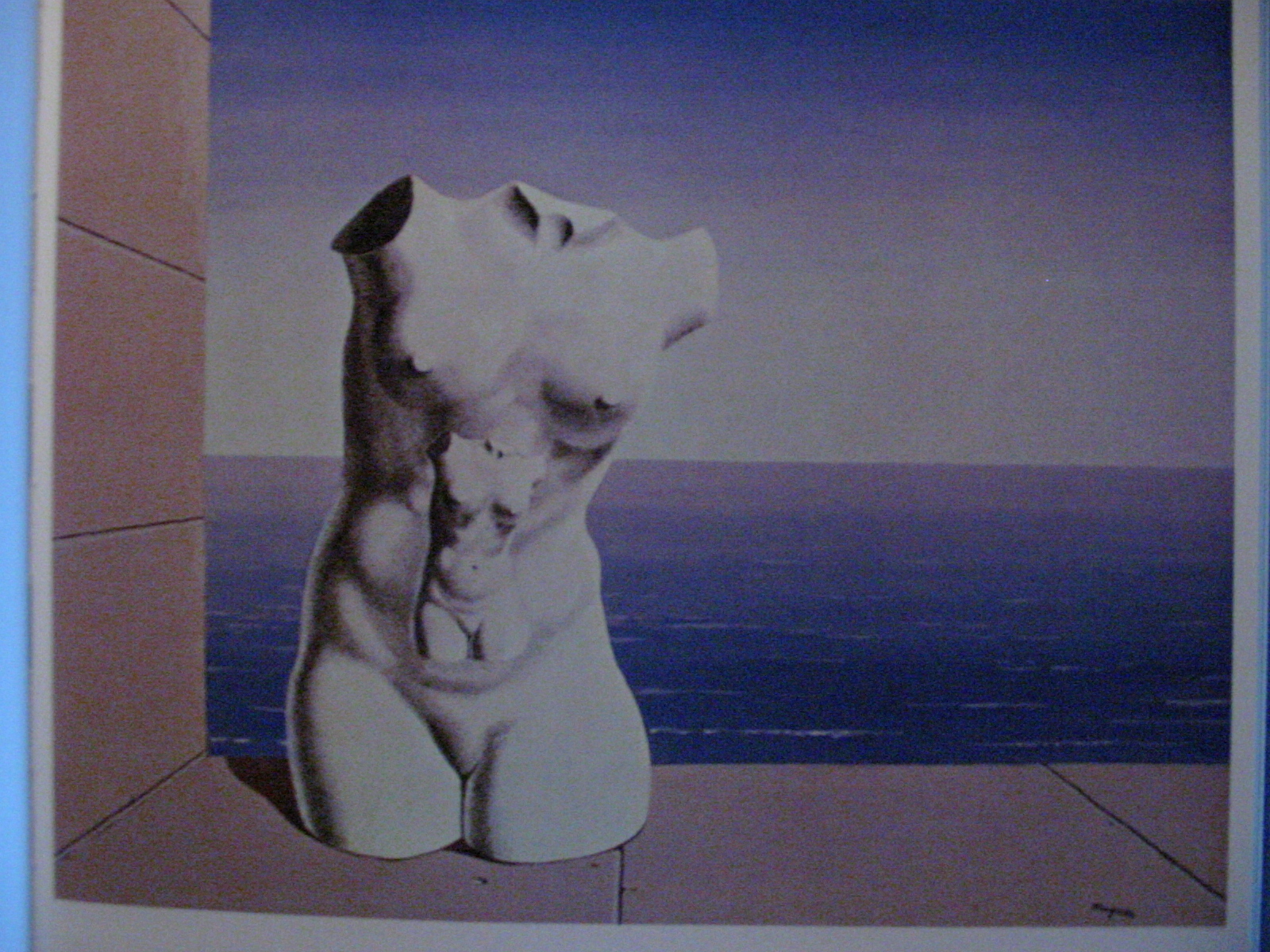

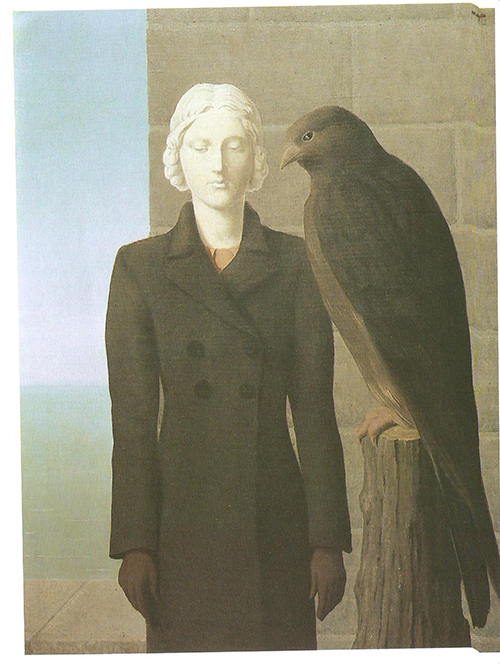

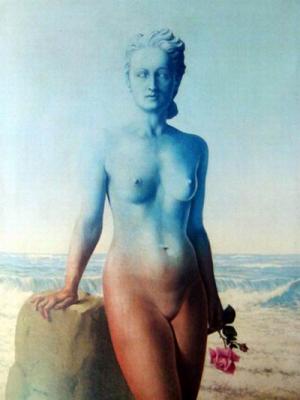

The Copper Handcuffs- 1931

Fashioned after Venus de Milo by Magritte, this small statue became this subject of several other paintings. The image of Venus de Milo facinated Magritte and other surrealists. Rene continued to explore with the paintings The Beauty of the Night (1932) and Light of Coincidence (1933). See the paintings below.

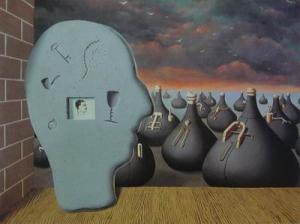

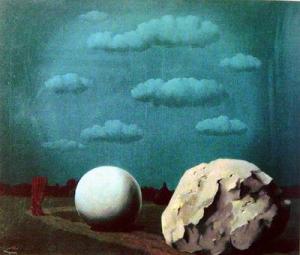

The Universe Unmasked (L' Univers Démasqué) 1932

The Tempest II-1932 gouche

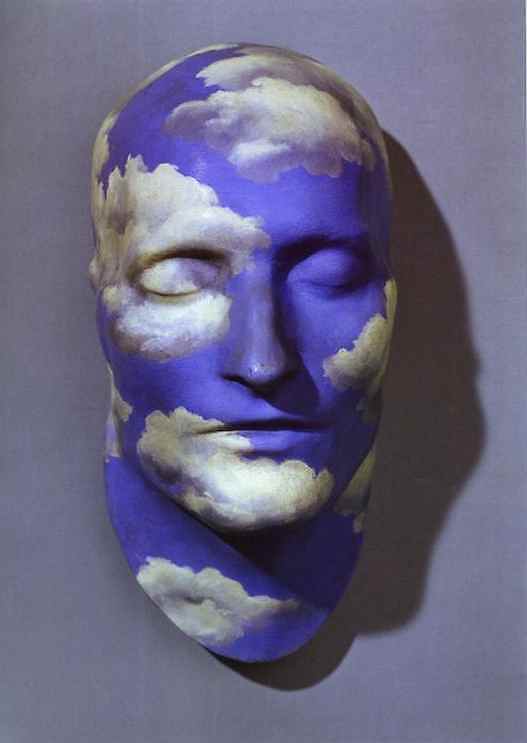

The Future of Statues (L'Avenir des statues) 1932. Oil on plâtre. 33.5 x 16.5 x 19 cm. Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisbourg, Germany. This was fashioned by Magritte after Death Mask of Napoleon.

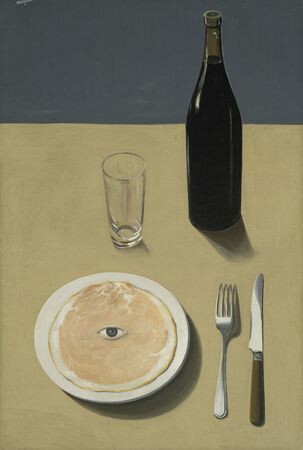

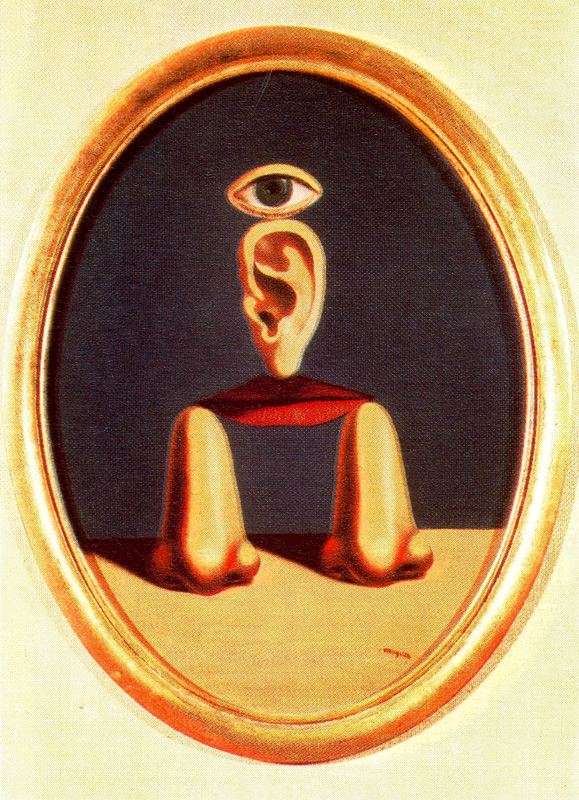

The Eye (L'Oeil vert) or the object (L'Object) 1932-1935

%201932.jpg)

The Monumental Shadow (L'ombre monumentale) 1932

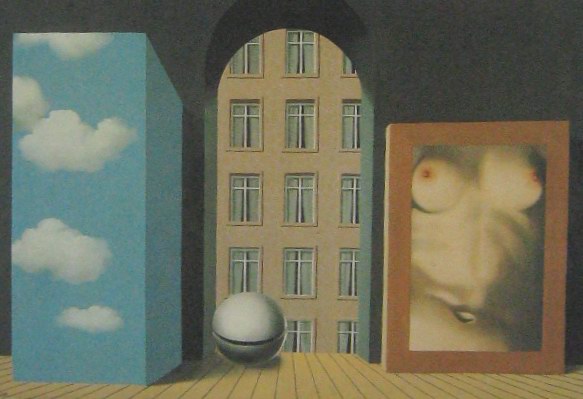

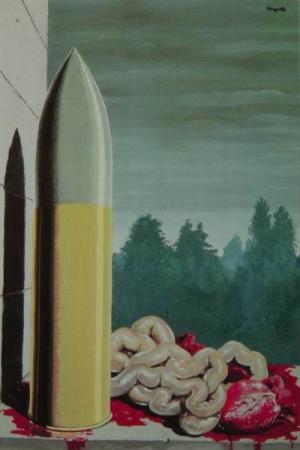

Act of Violence L'Attentat, 1932

The sky that we expect to see through the left window is really a solid block, through the middle arched window we see a building. The right panel resembles the torso in the 1930 Threshold of a Dream. Magritte continues his "act of violence" upon our perception of reality.

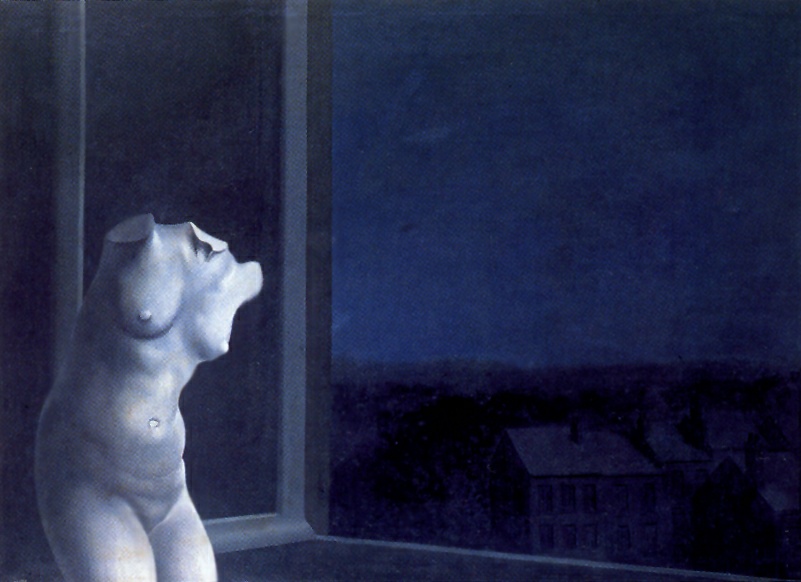

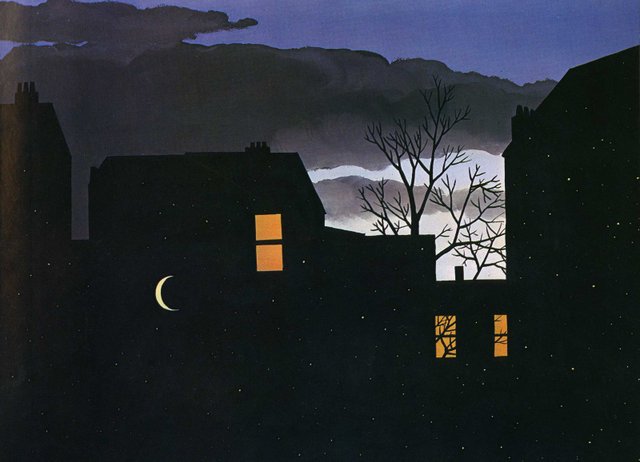

The Beauty of Night (la Belle de Nuit) 1932

This statuesque figure is very similar to 1933 The Light of Coincidence (See below). They are both fashioned after his miniature reproduction in plaster of the Venus de Milo (see above), a torso admired as the expression of feminine beauty in spite of the fact that it has no arms, the Copper Handcuffs (h. 370 mm, 1936; Paris, Charles Ratton priv. col.; see 1978–9 exh. cat., no. 200).

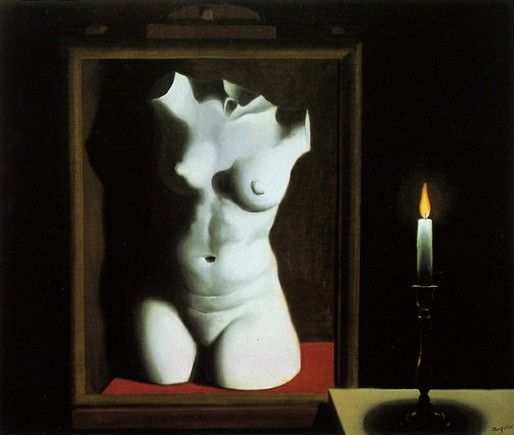

Light of Coincidence (La Lumière des Coïncidences) 1933 [23 5/8 x 28 3/4 x 2 1/4 in. (60.02 x 73.03 x 5.72 cm) Framed dimensions: 29 1/2 x 34 11/16 x 2 17/32 in. (74.93 x 88.1 x 6.4 cm)] Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jake L. Hamon

For the surrealist René Magritte, painting was a means of transcending reality to probe the mysteries of life. In contrast to other members of the Surrealist movement who probed the subconscious through trance states and automatic techniques, creating fantastic creatures and bizarre forms, Magritte developed a form of magic realism. He removed familiar objects, images, and sometimes words from their normal functions, arranged them in uncommon ways, and painted them with a precise realism or literalness that defies common sense and assaults the viewer's preconceived notions of the everyday world. In "The Light of Coincidences" Magritte questions the nature of art and reality. The antique torso and baroque motif of the candlelit interior are symbols of the representational traditions in art that had been cast aside by modernism. Magritte toys with the ambiguity between real space and spatial illusion by incorporating a picture of a woman's torso within the painting. The torso, which in reality would be a three-dimensional object in space, is depicted instead as the subject of a framed painting on an easel. This "painting," however, is highly realistic and introduces, via its trompe l'oeil precision, another "space" within Magritte's composition. "The Light of Coincidences" can be seen as an answer to Magritte's questions concerning the nature of light. According to Magritte, light is only real when received by an object. In this way, by illuminating the woman's torso with a candle flame, he has made light visible. Moreover, the candle establishes a mood of quietude and heightens the mysterious aura that was critical to his paintings. ["Dallas Museum of Art: A Guide to the Collection," page 133]

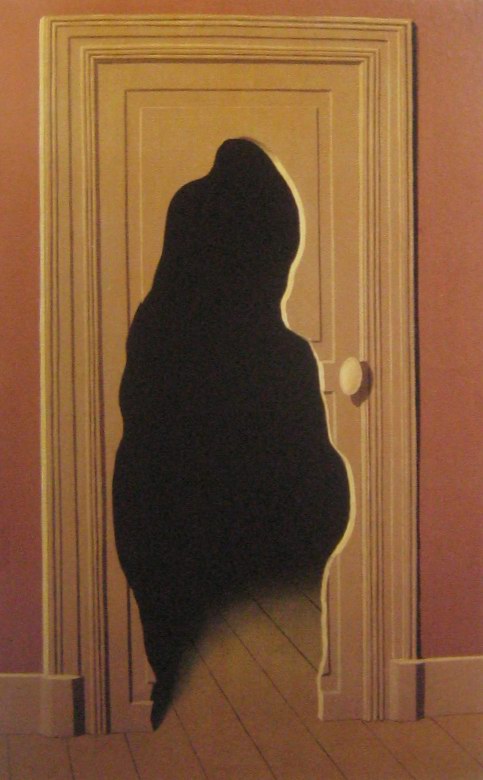

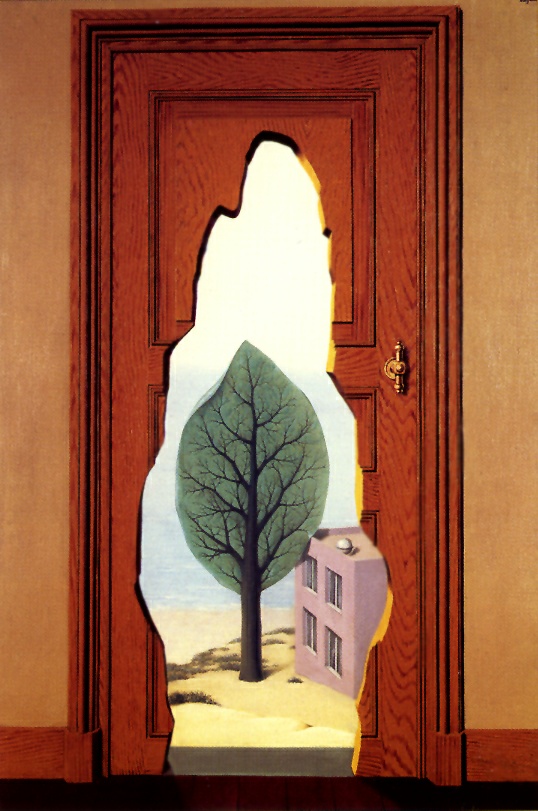

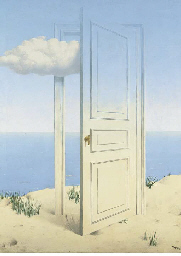

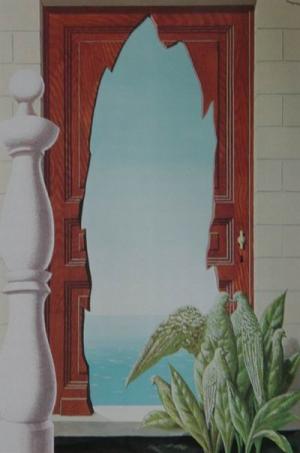

The Unexpected Answer- 1933

This is the first painting where Magrite explores the cutting of the door, and the door as a symbol. The outline is almost human in form resembling perhaps the outline of different people that pass through the doorway. Amorous Perpective (below) is his next exploration in 1935. There's an long article on my blog about this painting- check it out. Here's what Magritte said about this his best known door painting:

"Let us now turn to the panel of a door; this can be open to a landscape seen upside-down or else the landscape can be painted on the door. But let us try something less gratuitious: let us make a hole in the wall beside th door panel, a hole that is also a door panel, a hole that is also an exit- a door. Let us further improve this juxtaposition by reducing teh two objects to one: the hole goes quite naturally into the door panel. And through this hole we see darkness; this last image seems to be enhanced yet again if we light up the invisible thing hidden by the darkness, for our gaze always wants to go further and to see at last teh object, the reason for our existence."

The Unexpected Answer gives us a glimpse of what's behind the door- but there's no object just darkness. So we look into the darkness trying in vain to see the object. Very tricky Rene!

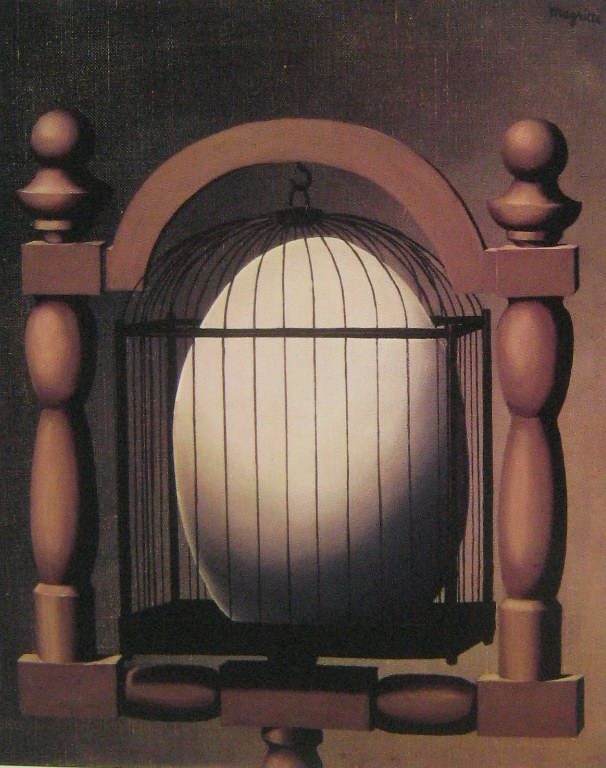

Elective Affinities (Les Affinites electives) 1933

According to History of Art: The artist is making free in a provocative and bewildering manner with the world of appearances. By placing in a birdcage not the bird itself but an egg of excessive proportions (Elective Affinities), he demonstrates the foolish cruelty of humans, constantly interested only in dominating others, in locking others up, in keeping the various forms of life under their control.

My take on this painting is quite different (I'm quoting the following event from memory). Magritte had a type of a vision or hallucination. He was sleeping and when he suddenly awoke istead of seeing a bird in the birdcage he saw an egg. Whether this event was a creation of his vivid imagination or he actually saw it was never known. The size of the egg really demonstrates this concept beautifully. Which comes first the bird...or the egg?

The Human Condition 1933

This is how Magritte himself explained the painting in 1938, "The problem of the window gave rise to La Condition Humane. In front of a window as seen from the interior of the room, I placed a painting (canvas and easel) that represented precisely the portion of landscape concealed by the painting. For instance the tree represented in the painting displaced the tree behind the painting outside the room. For the viewer the tree is simultaneously inside the room in the painting and outside the room in the real landscape."

Magritte continues, "This is how we see the world, we see it outside ourselves; and yet the only representation of it is within us. Similarily we sometimes remember a past event and the memory makes it a present event. Time and space lose that crude meaning which is the only one we have in our daily experience." [Translated from a 1938 lecture, La Ligne de vie]

"Questions such as 'What does this picture mean, what does it represent?' are possible only if one is incapable of seeing a picture in all its truth, only if one automaically understands that a very precise image does not show precisely what it is. It's like believing that the implied meaning (if there is one?) is worth more than the overt meaning. There is no implied meaning in my paintings, despite the confusion that attributes symbolic meaning to my painting.

How can anyone enjoy interpreting symbols? They are 'substitutes' that are only useful to a mind that is incapable of knowing the things themselves. A devotee of interpretation cannot see a bird; he only sees it as a symbol. Although this manner of knowing the 'world' may be useful in treating mental illness, it would be silly to confuse it with a mind that can be applied to any kind of thinking at all." -excerpt from Magritte's letter to A. Chavee, Sept. 30, 1960

"I have a great idea (not earth shattering) about the naive question, 'What does this picture represent?' My idea is that the questioner sees what it represents, but he wonders what represents the picture, and faced with the difficulty of figuring it out from this direction, he finds it easier and more fitting to ask what the picture 'represents.'

What represents the picture are our ideas and feelings--in short, whoever is looking at the picture is representing what he sees. This idea is not, some say, within the realm of knowledge, so it won't help me protect myself when the occasion arises."--excerpt from Magritte's letter to Paul Colinet, 1957

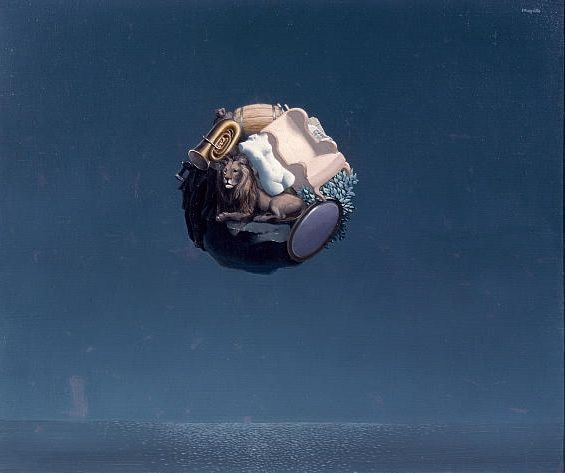

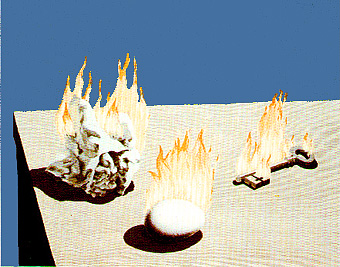

The Ladder of Fire I (L'Échelle du Feu) 1934

This is the first painting of the "Graditation of Fire" or "Ladder of Fire." Magritte compared this to the caveman's first discovery of fire. He said in a 1938 lecture, "The Ladder of Fire afforded me the priviledge of being acquainted with the feeling experienced by the first men who produced a flame by rubbing together two pieces of stone." He follows this up with his 1936 "The Discovery of Fire." The discovery is more apparent here; the paper can burn, the chair can burn, but the tuba cannot burn- making the burning tuba an impossible object. This impossibliltiy is what Magritte is trying to convey.

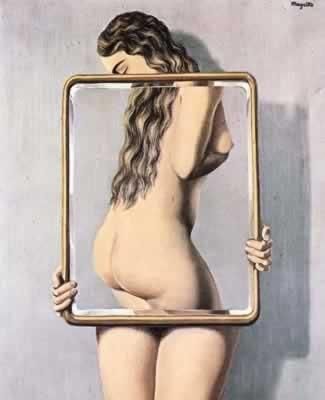

Dangerous Liasions- 1934

The Empty Picture Frame 1934

Le Rendez-Vous en chasse 1934

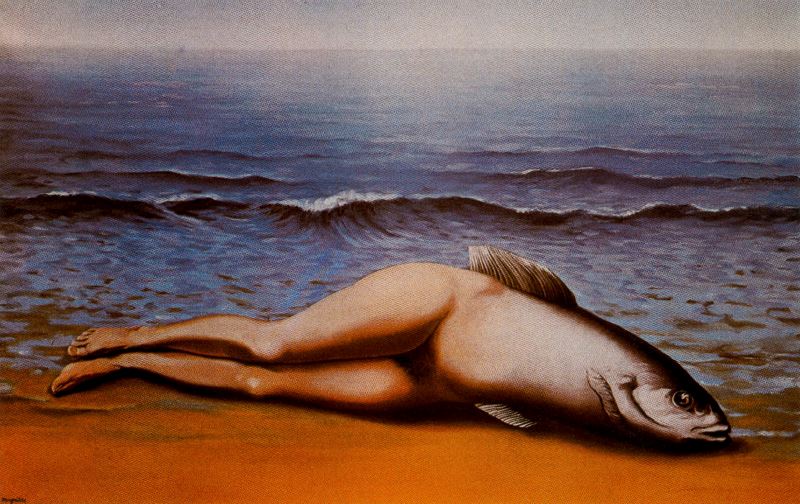

The Collective Invention 1934

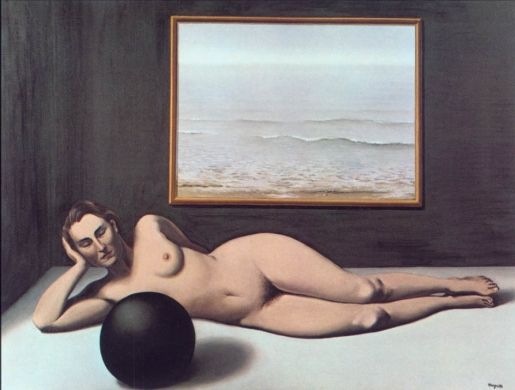

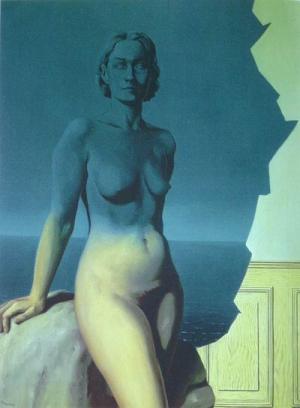

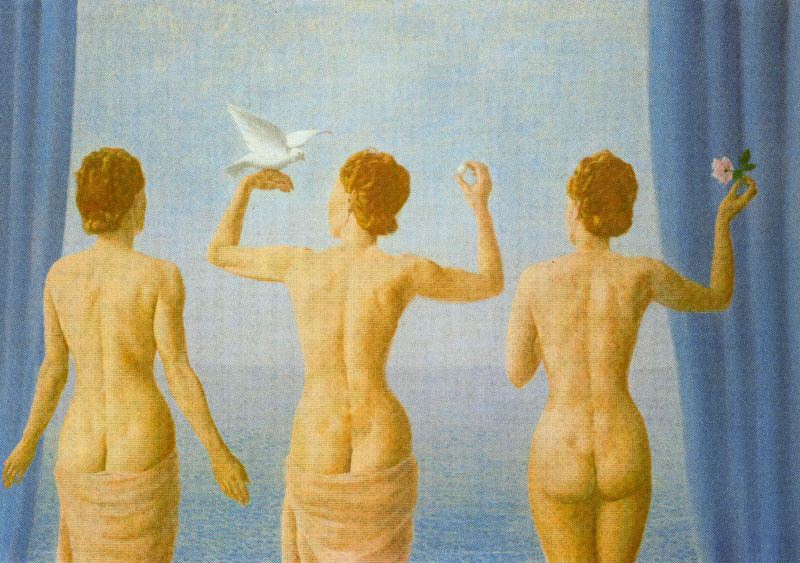

Black Magic 1934 (According to Sylvester)

The Black Magic series was a favorite of collectors according to Magritte. He painted many versions and I've included a similar version below that's probably from around 1934. Similar paintings by a variety of different names were done later in this decade. It's certainly one of Magritte's most striking nudes, a painting of his wife and muse Georgette. The original pose for the Black Magic series is "The Lifeline" (La Femme au fusil) 1930. "The Lifeline" pose is very similar as the wall is cut out except there is a rifle propped up against wall.

Of his Black Magic series Magritte said that "an undercurrent of eroticism is one of the reasons a painting might have for existing."

Magritte painted numerous versions, in one below titled "The Proud Ship" done in 1942 she holds a rose. In a letter to Paul Nougé of January 1948, Magritte wrote on the subject of the Black Magic paintings (Flowers of Evil 1946) as follows, "I am searching for a title for the picture of the nude woman (naked torso) in the room with the rock. One idea is that the stone is linked by some Affinity to the earth, it can't raise itself, we can rely on its generic fidelity to terrestrial attraction. The woman, too, if you like. From another point of view, the hard existence of the stone, well-defined, 'a hard feeling,' and the mental and physical system of a human being are not unconnected" (H. Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, New York, 1977, p. 173).

See the 1941 version below.

Black Magic Variation- 1934

(There was an image logo on the bottom part of the image- I removed part of it)

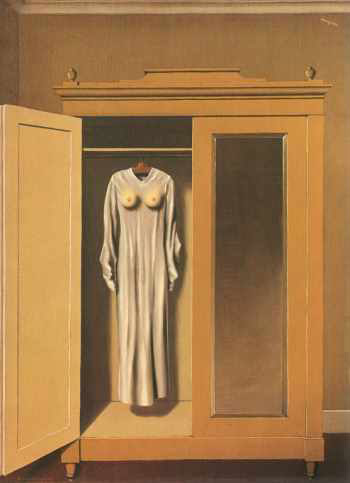

Hommage to Mack Sennett- 1934

Magritte's favorite movies were the Fantomas series released in 1912-1913. The surrealists enjoyed a wide range of silent movies — the comedies of Charlot (Charlie Chaplin) and Mack Sennett, the fait-divers films of Ferdinand Zecca, American melodramas sstarring Pearl White, horror films such as Wiene's Caligari and Murnau's Nosferatu, Robert Flaherty's South Seas documentary Moana, and the revolutionary montage of Eisenstein's Potemkin.

Mack Sennett (1880-1960) was an American motion-picture producer and director, who made a significant contribution to silent films in the United States with the frenetic slapstick comedy (including his popular Keystone Kops) that he introduced and perfected. Sennett was the film industry's first real producer, a versatile entrepreneur who recognized and encouraged talent and who created a systematic approach to production that yielded a large quantity of films.

Sennet, who had a fondness for rude visual humor, was paid tribute by Magritte with his own form of visual humor.

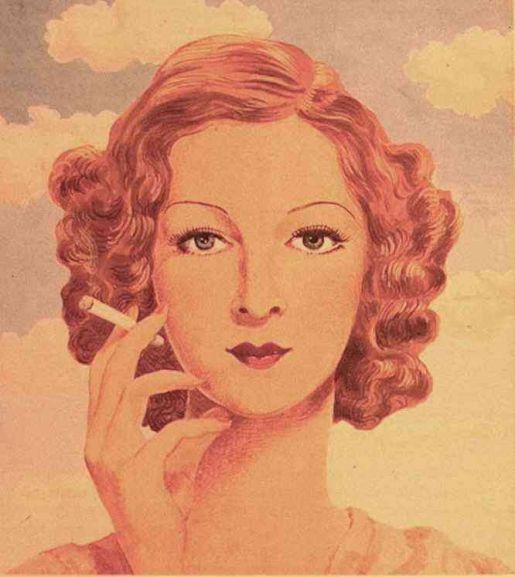

Georgette Magritte 1934 Poster

Clearly this pose, which looks like a cigarette advertizement, was used by Rene (minus the cigarete of course) for his famous painting The Rape (below).

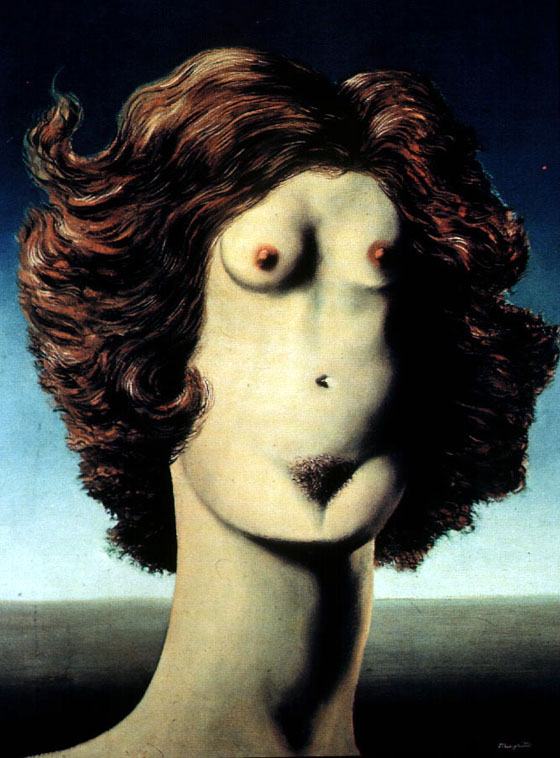

The Rape I

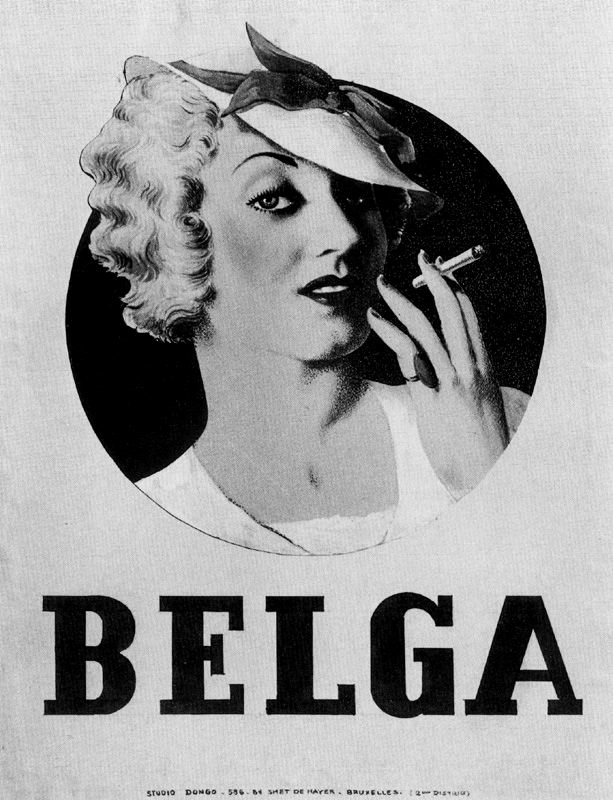

Ad for Belga 1935

The Bungler (La Gâcheuse) 1935

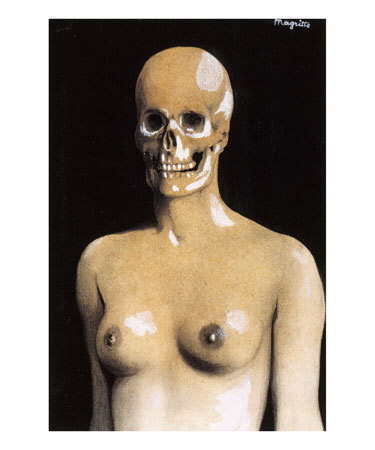

This painting is a Surrealist version of a vanitas painting, presenting youth and death in a wittily macabre combination. It is typical of Magritte’s work in that it is a finely painted scene which combines dramatically different elements in a deadpan style, making an illogical scene appear credible. Painted as a grisaille on tinted paper, it was made to be reproduced in black and white on the cover of the Belgian edition of the ‘Bulletin International du Surréalisme’. The painting formerly belonged to the jazz musician George Melly, who was involved with the British Surrealist Group while in his teens and was a great admirer of Magritte’s work.

The Discovery of Fire (Decouverte du feu) 1934-35

Perhaps this should have been named the Tuba Player's Nightmare or the Tuba Teacher's Hope. Certainly a mysterious and startling image. The fire is shown here with great effect against the dark background. What Magritte is trying to do is make you think what the real nature of fire is- normally a tuba cannot catch on fire and burn. By associating fire with an object that cannot burn, he tries to reveal the true nature of fire.

Perpetual Motion (Le Mouvement perpetuel) 1935, 21.3 x 28.7 in. / 54 x 73 cm

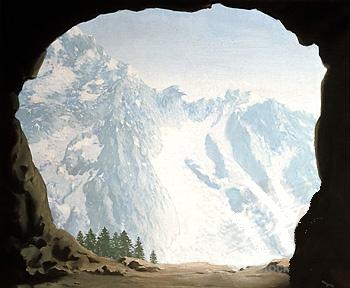

The Human Condition II (La Condition Humaine) 1935, oil on canvas, 54 cm x 73 cm; signed in grey paint lower right 'Magritte'; in black paint on reverse of canvas 'LA / CONDITION / HUMAINE / MAGRITTE / 1935'

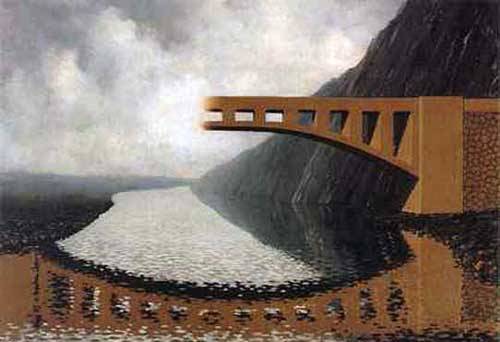

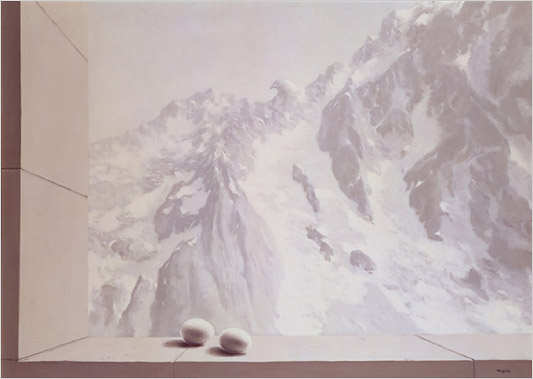

In this painting we look out through the mouth of a cave across a steep mountainous valley. In the centre of the painting, standing on an easel, is a painted canvas representing a castle. We are led to believe, but can never know for certain, that the painted castle conceals a real castle behind. René Magritte's work often explores the limits of knowledge and the power of illusion. Perhaps he chose the location of the cave because it makes reference to Plato's famous Parable of the Cave, itself a critique of human knowledge and understanding. The title of the painting is almost certainly a reference to Rousseau's statement: 'Our true study is that of the human condition.'

.jpg)

The Human Condition (III) Circa 1935

From various sources on the web this version appears as the Human Condition 1935. The version and information above is from a museum so it's probably accurate. Eventually I'll get some better information.

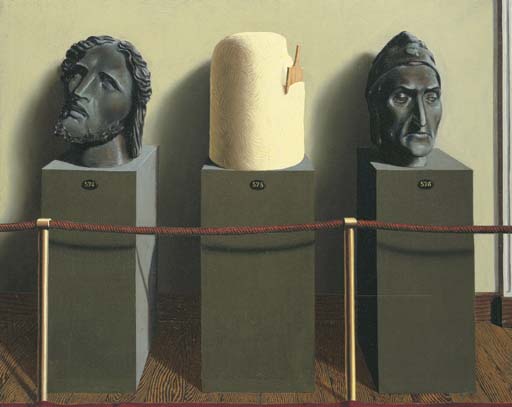

Eternity 1935 (L'éternité)

signed 'Magritte' (upper left); signed again, titled and dated '"L'ÉTERNITÉ" MAGRITTE 1935' (on the reverse) oil on canvas

25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 80.9 cm.) Painted in 1935

Provenance: Claude Spaak, Rixensart, Brussels (acquired from the artist, circa 1935). Stéphane Jasinki, Brussels (by 1956).

Mme. Jasinki-Bagage, Brussels (by 1959). Harry Torczyner, New York (acquired in the mid-1960s). The Museum of Modern Art, New York (gift from the above, 1972).

Literature: Letter from Magritte to Paul Eluard, December 1935. Letter from Magritte to E.L.T. Mesens, 30 November 1955.

P. Waldberg, René Magritte, Brussels, 1965, p. 84 (illustrated). A. Legg, M.B. Smalley, eds., Painting and Sculpture in The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1988, p. 72. D. Sylvester, René Magritte, Catalogue raisonné, London, 1993, vol. II, p. 212, no. 389 (illustrated).

Exhibited: Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, René Magritte: peintures objets surréalistes, April-May 1936, no. 21. (possibly) Brussels, Musée d'Ixelles, Magritte, April-May 1959, no. 37. (possibly) Liège, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Exposition Magritte, October-November 1960, no. 19. New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Art in the Mirror, November-February 1966, no. 23. Paris, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Peintres de l'imaginaire: symbolistes et surréalistes belges, February-April 1972, no. 127. Cincinnati, Taft Museum, René Magritte, 1977. Calgary, Glenbow Museum Four Modern Masters: de Chirico, Ernst, Magritte, and Miró, November 1981-January 1982, pp. 74-77 (illustrated, p. 75). Tokyo, Isetan Museum of Art, Surréalisme, February-March 1983, no. 47. Lausanne, Fondation de l'Hermitage, René Magritte, June-November 1987, no. 35 bis (illustrated). Canberra, National Gallery of Australia; Brisbane, Queensland Art Gallery and Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Surrealism, Revolution by Night, March-September 1993, no. 174. Ostend, Provinciaal Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Van Ensor tot Delvaux: Ensor, Spilliaert, Permeke, Magritte, Delvaux, October 1996-February 1997. New York, The Pace Gallery, René Magritte: Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings, May-June 1990, no. 3 (illustrated).

Notes: L'éternité expresses the full force of Magritte's alien yet authoritative visual power. Unlike many of his other works, however, L'éternité was not the result of an immediate inspiration, a vision or conception, but instead evolved from an idea given to Magritte by his friend Claude Spaak, the first owner of the painting. Spaak claimed that his original notion was the sight of a gallery wall hung with paintings, and between them stood a large ham. However, by December 1935, this idea had already evolved significantly in Magritte's mind:

I am busy at the moment on a rather amusing picture: in a museum, there are three stands against a wall, with statues of Dante and Hercules to the left and right while the one in the centre supports a magnificent pig's head with parsley in its ears and a lemon in its mouth' (Magritte, letter to Paul Eluard, December 1935, quoted in D. Sylvester and S. Whitfield, René Magritte Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. II: Oil Paintings and Objects, 1931-1948, London, 1993, p. 212).

In the final state of his conception, Margritte employed busts of Christ and Dante with a slab of butter placed in the middle. These epic busts give the impression of being relics that have survived--if only as fragments--through centuries of turmoil representing the idea of 'eternity' in the title. However, between them, monumental in its own way, is the fresh but perishable butter, a jarring contrast that assaults the viewer's rational sensibilities. Time, and the authority of the museum, have been turned on their heads, as Magritte forces his museum-goer to look beyond his preconceptions and to contemplate the internal and external reality of this painted world in all its paradoxical wonder.

God Is Not a Saint Dieu N'est pas un Saint, 1935

Love-disarmed (L'Amourdesarme) 1935

Heraclitus' Bridge (Le pont d'Heraclitus) 1935 oil 54x73 cm

Composition on a Sea Shore- 1935

Bather Between Light and Darkness 1935

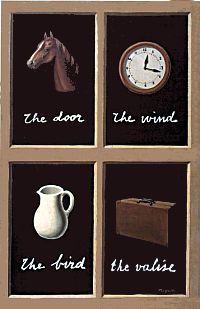

The Interpretation of Dreams III- 1935

Magritte turns essentialism on its head with The Interpretation of Dreams (1935), which features images of everyday objects titled by words that do not describe them. This is his third version and apparently he was planning to exhibit this in London becasue he includes English words for the first time. Three of the captions are incorrect (The English ones!). Here's a quote online: "This arbitrarily reconstructed verbal/imagerial lexicon evinces that, in an alternate, oneiric state of logic, words and objects can acquire new relationships, as they are not transcendentally united."

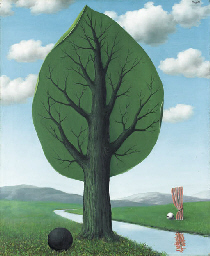

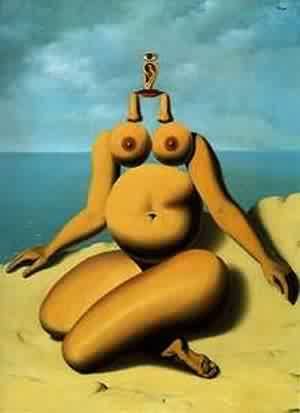

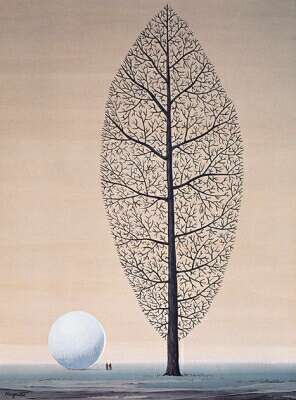

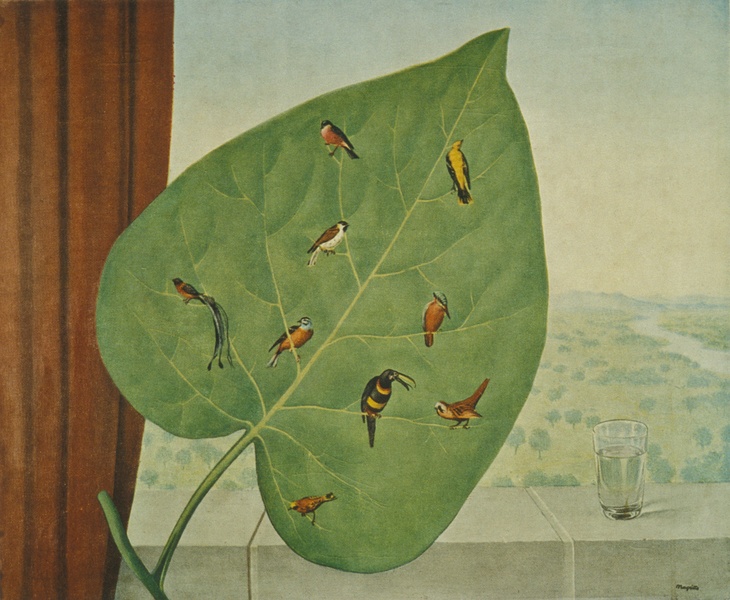

The Giantess II (La géante II) 1935, Signed 'magritte' (upper right); signed, titled and dated 'LA GEANTE MAGRITTE 1935' (on the reverse) oil on canvas 28¾ x 23 5/8in. (73 x 60cm.)

Provenance: Paul-Henri Spaak, Brussels, by 1936; Margaret Krebs, Brussels, by whom acquired in the 1960s; Ado Blaton, Brussels, by whom acquired from the above; Jacky Ickx, Brussels, a gift from the above, his father-in-law; Anon. sale, Sotheby's London, 12 November 1970, lot 70 ; Acquired at the above sale by the father of the present owners.

Literature: Letter from Magritte to André Breton, July 1934; R. Magritte, La ligne de vie, a lecture given in Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum van Schoone Kunsten, 20 November 1938; P. Waldberg, René Magritte, Brussels, 1965, p. 227 (illustrated). F. Cachin, 'Magritte, ou Mandrake contre Maigret', Preuves, Paris, July 1966, p. 80; ed. D. Sylvester, René Magritte, Catalogue raisonné, vol. II, Oil Paintings and Objects, 1931-1948, Antwerp, 1993, no. 362 (illustrated p. 194); ed. D. Sylvester, René Magritte, Catalogue raisonné, vol. V, Antwerp, 1997, Chron. 38.5.2, p. 21 (reconstructed text of the 1938 lecture).

Exhibited: Antwerp, Feestzaal, Kunst van heden: salon 1935, July 1935, no. 145; Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, René Magritte: peintures, objets surréalistes, April-May 1936, no. 26; Rotterdam, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, René Magritte: het mysterie van de werkelijkheid, Aug.-Sept. 1967. This exhibition later travelled to Stockholm, Moderna Museet; Charleroi, Palais des Beaux-Arts, 'Hommage à René Magritte', 41e salon du Cercle Royal Artistique et Littéraire de Charleroi, Feb. 1968, no. 130.

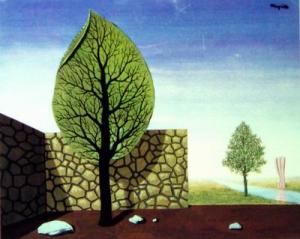

Notes: The first "The Giantess" done in 1930 featured a miniture man entering a room with a seemingly huge nude woman towering above him (see: Paris Years).

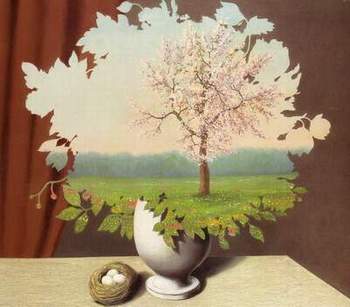

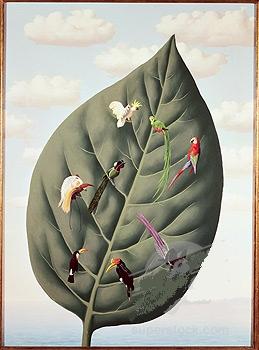

Notes from Cristies: Writing to André Breton in 1934, Magritte discussed the seeds of the idea that led to the creation of La géante (The Giantess), saying that he was 'trying… to discover what it is in a tree that belongs to it specifically but which would run counter to our concept of a tree' (Magritte, letter to Breton, quoted in ed. D Sylvester, op. cit., vol. II, p. 194). This was a part of Magritte's pioneering adventures into the nature of the world and our perceptions, disrupting the absolute expectations people have about the nature of specific objects. So with the tree, Magritte sought the idiosyncratic, signature element that he could disrupt in order to confront the viewer with a new, fresh view of the tree. He did this by twisting the associated elements of the object - in this case the tree - forcing the viewer's reappraisal of the commonplace. This solution was disarmingly simple: 'The tree, as the subject of a problem, became a large leaf the stem of which was a trunk directly planted in the ground. I called it "The giantess" in memory of a poem by Baudelaire' (Magritte, quoted in ed. D. Sylvester, vol. II, loc. cit.). In this way, an integral feature of the tree here becomes its dominant feature, as the tree is completely subsumed by its own leafiness. La géante is the first example of this thematic subject in Magritte's work, although it was an image that he found so effective that it would recur again and again, to various effects, throughout his career.

Magritte was often adamant that his titles had little to do with the contents of a painting: 'The titles of my paintings accompany them like the names attached to objects without illustrating or explaining them' (Magritte, letter to Barnet Hodes, 1957, quoted in H. Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, trans. R. Miller, New York, 1977, p. 203). Magritte often named pictures after writings he particularly admired, as he claimed with La géante. Nonetheless, vague thematic links can often be perceived between his works and their titles, not least here, where a giant leaf has taken the place of the tree. However, the connections between the title and the subject in Magritte's works are usually of sufficient opacity that they provide more questions than answers. In the poem La géante mentioned by Magritte, Baudelaire imagines himself exploring and roaming over the body of a giantess. The poem is packed with a strange sensuality induced by Baudelaire's descriptions - the language is in part tainted and debauched. This relates strongly to the mingled existential nausea and celebration of the tree in La géante. The vast scale of the leaf relates to Baudelaire's exploration of a vastly magnified feature from life, while the unsettling image also induces a similar sense of the disturbing recognisable unreality of the scene. La géante perfectly encapsulates the quality of Magritte's work that makes 'superreality' a more appropriate translation of surréalisme. He himself wrote that, 'For me, it's not a matter of painting "reality" as though it were readily accessible to me and to others, but of depicting the most ordinary reality in such a way that this immediate reality loses its tame or terrifying character and presents itself with its mystery' (Magritte, quoted in H. Torczyner, ibid., p. 70). Humour and the absurd here mingle in Magritte's unique vision to force the viewer to see the world in a new, more appreciative way.

Magritte deliberately avoided attracting too much attention in his lifetime, and therefore little biographical material of interest exists. However, La géante is linked to several important factors in Magritte's life and career, not only in that the idea was voiced in a letter to Breton, with whom Magritte had sundered links in 1930. Although from their rupture Magritte had insured that the more grounded Belgian Surrealism kept a distance from their French counterparts, a correspondence resumed. Indeed, in 1935, Magritte was amongst the signatories of a tract marking the Surrealists' break with the Communist party, especially after their mistreatment of Breton, and participated in several other international Surrealist projects. For Magritte, who usually avoided overtly political matters in life and in his art, this was a period of surprising political activity.

As well as his political activity, 1935 saw an increase in Magritte's artistic output. This was in part due to the sponsorship of Claude Spaak. Spaak was a playwright, but had also been an active collector of Magritte's paintings for some time. In 1935, he made a semi-formal arrangement to allow Magritte to abandon commercial work and focus fully on his own artistic output. To this end, he provided the artist a monthly stipend, while also guaranteeing the paintings he produced. In addition to this, Spaak actively sought other sponsors for Magritte, and managed to encourage several people to collect his paintings, even some like his father who seem to have shown little interest in the art. Amongst the more active of these collectors was Paul-Henri Spaak, Claude's brother, who already owned La géante the year after it was painted. The Spaaks were thus largely responsible for Magritte's advances in his art during the 1930s, allowing him to concentrate fully on the development of his thought and craft. Many of the most iconic images that recur throughout Magritte's oeuvre first appeared during this amazingly fertile period of his life and career, which saw the germination of much of Magritte's style. La géante is therefore a testimony to the flourishing of Magritte's art and to those who facilitated it.

The Amorous Perpective (The Amourous Vista) La Perspective amoureuse 1935

This painting combines The Unexpected Answer and The Giantess II.

The Red Model- I (Le Modèle rouge), 1935 Oil on canvas, 72x48.5 cm

The Red Model, with its virtually flat perspective and matter-of-fact style, consolidates two apparent opposites through an open visual riddle-an obvious metaphor. It shows inside and outside simultaneously. A few years earlier, in 1933, Magritte had painted a door that was open and closed at the same time, in The Unexpected Answer. The Red Model II (below) Le modele rouge II was painted in

1937.

Portrait 1935

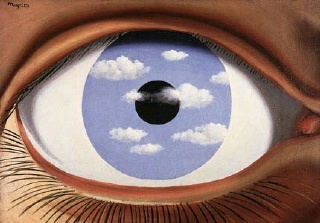

The False Mirror II (le faux miroir II) 1935

The False Mirror II is the second version done in 1935 featuring eyelashes. The 1928 version of False Mirror was adapted as the CBS TV logo in 1951. The clouds were removed from the CBS logo the next year possibly to avoid a lawsuit from Magritte and his NY lawyer.

Georgette 1935

The Meditation 1936

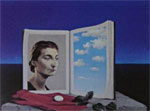

Portrait of Eluard- Also titles The White Magic (La Magie blanche)- 1936

La Magie blanche, René Magritte (1936) by Ainsley Brown 2005

In 1936, René Magritte drew a portrait of Paul Éluard. While this portrait is largely absent from catalogues of the painter's ouvre, the image is extremely significant with respect to the interartistic conversation between the painter and the poet. Also, while Paul Éluard wrote numerous poems for painters during his career, Magritte did not have a particular predilection for the representation of poets. Since the Éluard portrait does not belong to a larger group of poet portraits, its existence is all the more intriguing. Compared to many of his other portraits, Magritte's depiction of Éluard is quite traditional. In portraits such as Paul Nougé (1927), Gustave van Hecke (1927) or Georgette (1935), Magritte introduces recognizable figures into paranormal environments. It is the startling juxtaposition of the supernatural and the accurate or hyper-real (with respect to the depiction of the portrait subject) that gives the Magrittean portrait its specific allure. However, the 'magic" of La Magie blanche is subtle to the point of being nonexistent. Magritte's use of veiled magic to represent Éluard recalls the fact that he claimed to admire Éluard's ability to recognize "reality not separated from its mystery [8]" (Magritte 536, my translation).

Pencil in hand, seated demurely next to a naked female torso, the poet is represented in the act of writing. His physique is portrayed with clarity and detail: the majestic forehead, distinctive hairline and lightly pursed lips can belong to none other than Paul Éluard. While the precision in the representation of the poet is notable, such accuracy or 'correctness' is coupled with a lingering sense of "impossibility" with regard to the scenario envisaged. Éluard is writing directly onto the skin of the abdomen of the woman, as if the stroke of his pencil were capable of breathing life into her. The boundaries between the two bodies are difficult to distinguish; the poet and the woman appear to fuse seamlessly into each other. Éluard's physical positioning in relation to the naked torso is loaded with erotic signification: the poet's hand and forearm hide her vaginal area and along with the outstretched pencil they form a phallic trio which projects onto her body. Establishing a visual link between poetry and sex, Magritte depicts poetic writing as an erotic exploit; it is presented as the sexual act itself, capable of creating and giving life to new forms.

One of the intriguing features of La Magie blanche is that it can be read simultaneously as a portrait of Éluard and as a self-portrait of Magritte. Boundaries between the Self and the Other are blurred and the (con)fusion of Magritte and Éluard ensues. The 'synthesis' between the painter and the poet is further intensified by the fact that La Magie blanche bears a strong resemblance to La Tentative de l'impossible (1928), one of Magritte's rare self-portraits. In this image he represents himself in the act of 'painting Georgette': a (failed) fantasy of bringing the woman to life through art which, aside from its reference to the Pygmalion myth, is echoed in his portrait of Éluard almost a decade later. For in La Magie blanche, Magritte represents Éluard as he had represented himself in La Tentative de l'impossible . In his self-portrait, Magritte's brushstroke - like the stroke of Éluard's pencil - attempts to give life to the female form. While this is the male Surrealist fantasy par excellence , such efforts can only prove futile: textual and pictorial significations are insufficient and the woman remains insaisissable . Nonetheless, the parallel between La Magie blanche and La Tentative de l'impossible is intriguing, especially in the context of this exploration of the dialogue between Self and Other, poetry and painting, Belgian and French Surrealism. Is Magritte's portrait of Éluard the displaced double of his own self-portrait from 1928? This delayed parallel between the two portraits is not inconceivable, especially since in La Magie blanche, Magritte privileges the representation of the common ground he shares with Éluard rather than focussing on the specificity or the distance that separates them. Placing the accent on the similarities between their two practices, Magritte makes the portrait a space of dialogue between Éluardian poetics and his own aesthetics.

%201936.jpg)

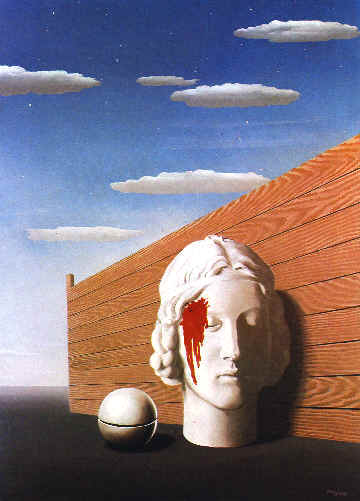

Heart Revealed- Portrait of Tita Thirifays (Le Coeur Devoile - Portrait de Tita Thirifays) 1936

Tita Thirifays was the wife of Andre Thirifays, a Belgian film critic. In 1938 by Henri Storck, André Thirifays and Pierre Vermeylen founded The Royal Belgian Filmarchive (Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique). Ever since it has been preserving a collection of films with a permanent esthetical, technical and historical value.

The Giantess III (La géante II) - 1936

This variation was done a year after the "The Giantess II (La géante II), see above. The first "The Giantess" done in 1930 featured a miniture man entering a room with a seemingly huge nude woman towering above him (see: Paris Years).

Portrait d'Irène Hamoir, 1936

Irene Hamoir (1906-1994), poetess and novelist, was one of the central female figures of the surrealist movement in Belgium. Irene Hamoir was born the July 25th 1906 in Saint-Gilles (Brussels). Her father Léopold Hamoir was a hatter. Her paternal grandmother, unmarried, had two children with Léopold Noiset, racing cyclist, manufacturer of motorcycles, and driver for the Swift-club of Brussels. Around 1890 the children and Leopold teamed up to form a motorcyle and car act named “Nice Noazetts.” Later when the children were older they became “The Noisets,” international sensations. They specialized in spectacular motorcycles and cars acts called “The Infernal Tank," “The Table of the Devil,” and “The Leap of Death.” Irene Hamoir memorialized the antics of her uncles in her collection of stories, "The Infernal Tank" written between 1932 and 1939, then in an article published in 1949 in the illustrated magazine, Evening.

After attending busines school in 1922 Irene Hamoir became the secretary of a tannery-dyeing company. Militant socialist, she took part in many socialist meetings around 1924. When she approached Camille Huysmans in 1925 with her first poem, she met the painter Marc Eemans, who became her first serious relationship. After collaborating in the review, Distances, which brought together the surrealist group of Brussels, in 1928 Irene Hamoir met Louis Scutenaire at Marcel Lecomte's house. In 1929 she became secretary for the Economic and Financial Agency of Brussels, while Scutenaire continued writing poetic letters to her daily. She married him in 1930 and, after a voyage to Paris and in Spain, they settled at Alfalfa Street where he lived with his mother.

In 1931 Irene Hamoir began her career as a civil servant at the International Court of justice, travelling between Geneva and the Hague where Scutenaire sometimes came to join her. Soon she became a civil servant for the court in Brussels. Irene and Louis attended the meetings of the surrealist group in Brussels, with Paul Nougé, the brothers Magritte, the musician Andre Souris, Marcel Lecomte, E.L.T. Mesens, Paul Colinet, Marcel Mariën. They also were part of the Paris surreaist group.

Irene Hamoir atended the 1935 International exhibition of surrealism in Louvière. The next year Rene Magritte painted her portrait. "The beauty broke its odd sheath, gave pinks to the fountains" wrote Hamoir. In August 1937 Scutenaire remained in Céreste (Provence) at Rene Char while she found work in the Hague until November and the realtionship with “Scut” became strained. In 1939 Irene Hamoir left her post of civil servant, contributing two numbers to the review, The Collective Invention (with a photograph of Raoul Ubac).

Irene Hamoir and Scutenaire left Brussels in May 1940 with Magritte, Agui and Raoul Ubac. Being separated in Paris, they are finally reached Carcassonne where they meet Joe Bousquet, Jean Paulhan, André Gide, Gaston Gallimard. After a stop in Nice, they returned to Brussels in October where Hamoir found work in 1941 at the National Bank of Belgium. From 1942 to 1945 she was the director of the sales for the Belgian Chemical Union. Her collection of writings, The Infernal Tank, appeared in 1944 and she began drafting of the newspaper, the Evening. Irene Hamoir contributed in 1945 to the magazine reviews "Public Safety," "The Blue Sky" and "The Earth is Not a Vale of Tears" featuring Marcel Mariën's photos. She published poems in 1946 in the Two Sisters that Christian Dotremont published, the second poem, an “exquisite corpse” was signed by her, Rene Char, Paul Éluard and Scutenaire. She also contributed to "To know To Live" by Magritte.

Under the name of “Irene” she published in 1949 a collection of sound poems. Irene Hamoir collaborated in the following years with several other reviews, particularly the 1953 "Mixed Temps," created by André Blavier and Jane Graverol. The same year she published her novel "Boulevard Jacqmain," in which the members of the Belgian surrealist group appear under nicknames, Nouguier for Paul Nougé, Gritto for Rene Magritte, Maître Bridge for Scutenaire, Edouard Massens for E.L.T. Mesens, Bergère for Georgette Magritte, Marquis for Paul Magritte, Sourire for Andre Souris, Mr. Marcel for Lecomte, Evrard for Geert Van Bruane, and Crépue for her. In 1955 Irene Hamoir started to write features for the Petite Gazette. She wrote for the last issues of Evening, tributed to Gerald Van Bruane in 1964, and Marcel Lecomte in 1966, before retiring.

Irene Hamoir published several plates of poems in 1971, 1972 and 1975. In the same decade she and Louis Scutenaire wrote about their experiences with their painter friends Roland Delcol, Tom Gutt, Yves Bossut, Claudine Jamagne, Rachel Bases, Robert Willems, and Roger Van de Wouwer. About 1976 she contributed regularly to the review, the Vocative, published by Tom Gutt and contributed to Isy Brachot her poetic works Corne of Brown. In 1982 Irene Hamoir and Scutenaire wrote “Her and Him,” a foreword for the retrospective Rene Magritte and surrealism in Belgium. After the death of Scutenaire in 1987, some of their correspondences with Andre Bosmans, Paul Nougé, and Marcel Mariën, are published in the review, the Naked Lips. In 1992 she wrote for Croquis, which gathered her chronicles for the review, Evening. She died in Brussels the May 17th, 1994.

In the retrospective “Irene Scutenaire-Hamoir” organized by Tom Gutt executor with the Royal Museum of Modern Art in Brussels (Royal Musées of the Art schools of Belgium) appeared many works of the painter Magritte (more than one score of paintings, a score of gouaches, forty drawings, etc) which were hanging on the walls of their house on Alfalfa street including: Portrait of Nougé (1927); the Robber (1927); Discovered (1927); Man Meditating On Madness (1928); Portrait of Irene Hamoir (1936); Defense of Raading; Belle Canto (1938); The Great Hopes (1940); The Fifth Season (1943); The Smile (1943); The Harvest (1943); Good Omens (1945); Natural Meetings (1945); Thousand and One Nights (1946); the Intelligence (1946); Lyricism (1947); Lola de Valence (1948). The paintings are now located at Royal Museums of the Art School of Belgium. [from a biography translated by Richard Matteson]

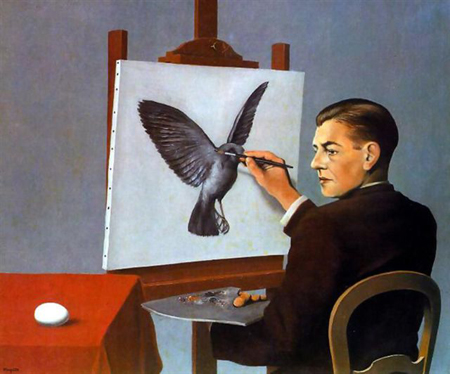

The Clairvoyance 1936

Clairvoyance (La Clairvoyance, 1936) is one of Magritte's better known works and perhaps his best self-portrait. Using his best sense of the absurd, he captures the unique meaning of what an egg becomes in a hilarious way.

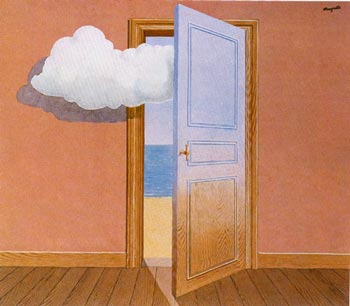

The Key to Fields (La Clef des champs) 1936, 31.5 x 23.6 in. / 80 x 60 cm

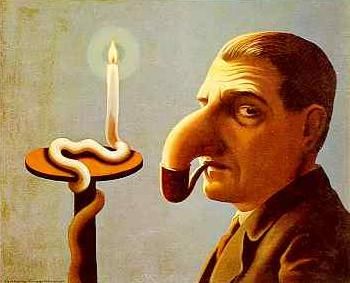

Philosopher's Lamp (La Lampe philosophique) 1936

Using the same snake-like candles that are found in "The Meditation" (above), Magritte give new meaning to "put that in your pipe and smoke it."

The Precursor III or The Chamber of the Barley (Le Precurseur III or La Chambie de L'Orge) 1936

The percursor (aptly named) to the Domain of Arnheim paintings. A similar cave setting was used the year before in The Human Condition II (La Condition Humaine) 1935- see above.

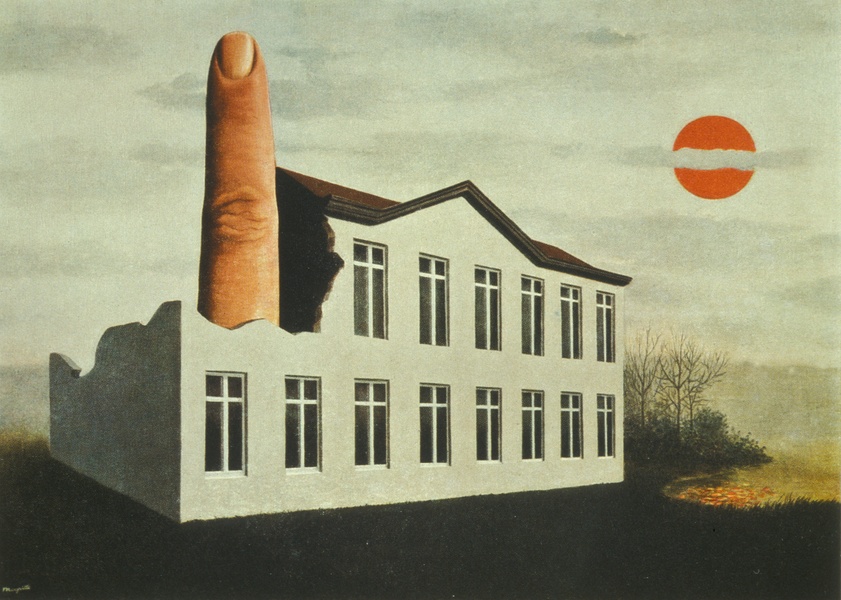

The Revealing of the Present (La revelation du present)- 1936

This painting is fairly rare and I stumbled upon the image while spinning the web. I translated the title from German so Magritte can now contact me from the great beyond to thank me. He frequently asked his friends to come up with irrelevant titles to his work to "add even more" mystery. There's not much to say about this painting but, "watch out for his index finger!" See another finger painting below.

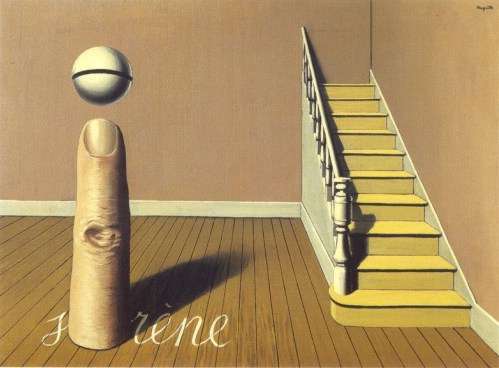

Forbiden Literature or The use of the Word (Irene)- La Lecture Defanse ou L'Usage de la Parole, 1936

The Forbiden Literature or the Use of the Word (Irene) 1936 seems to be a inside joke involving Irene Hamoir (see her portrait above), who was a poet and the wife of his friend Louis Scutenaire. Notice how Magritte uses a CAPITAL letter I to spell her name. Cursive indeed!

The Healer (Le Therapeute) 1936

This is the first of several version of The Healer (Le Therapeute).

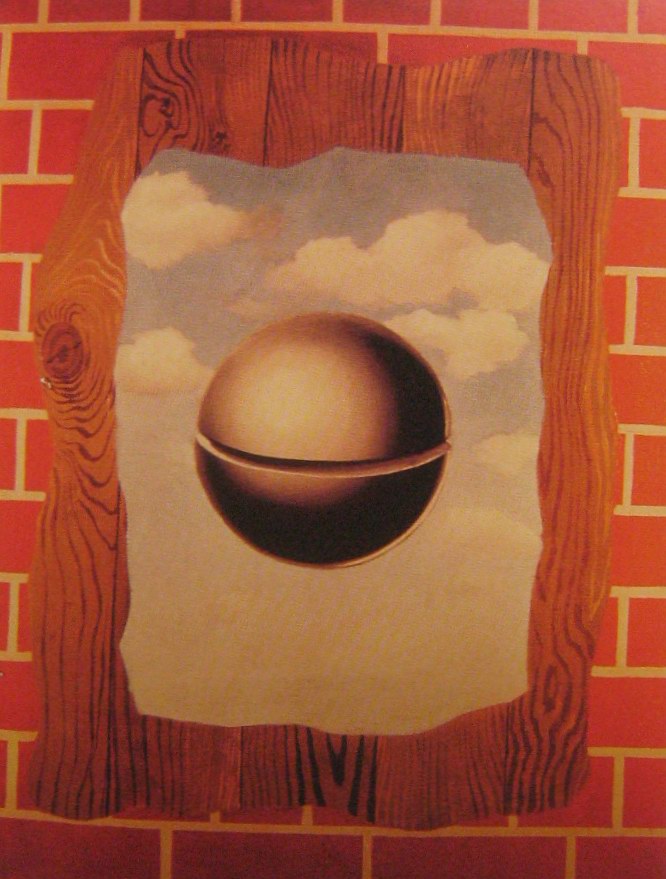

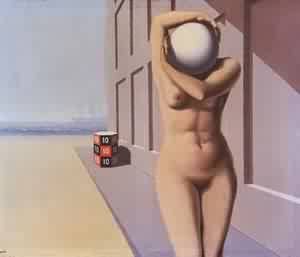

Spiritual Exercises (Exercices spirituels) 1936 signed 'Magritte' (lower left); signed again, dated and titled 'MAGRITTE 1936 "EXERCICES SPIRITUELS"' (on the reverse) oil on canvas 23¾ x 28¾ in. (60.3 x 73 cm.)

Back to Magritte's favorite subject material- nude women. Here the orb replaces the girl's face but it's not just an image, Magritte gives it substance by having her wrap her arms around it. Behind her is some form of mental game where numbers are matched.

Provenance: Stéphane Cordier, Brussels (acquired from the artist, by 1938); Private collection, Brussels; Carl Laszlo, Basel (by 1966).

Macklowe Gallery & Modernism, New York; Acquired from the above by the late owner, November 1988.

Literature: D. Sylvester, ed., René Magritte, Catalogue Raisonné: Oil Paintings and Objects 1931-1948, New York, 1993, vol. II, p. 223, no. 407 (illustrated). R. Hughes, The Portable Magritte, p. 436 (illustrated in color, p. 160).

Exhibited: Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, René Magritte: peintures, objets surréalist, April-May 1936, no. 15; Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Les Compagnons de l'art, June-August 1938, no. 274; Knokke, Casino Communal, XVe festival belge d'été: L'Oeuvre de René Magritte, July-August 1962, no. 47; Bern, Kunsthalle, Phantastische Kunst Surrealismus, October-December 1966, p. 6, no. 72 (illustrated); Hanover, Kestner Gesellschaft and Zurich, Kunsthaus, René Magritte, May-July 1969, no. 35 (illustrated, p. 111).

Basel, Galerie Beyeler, Nudes--Nus--Nackte, June-August 1984, no. 41 (illustrated in color); Lausanne, Fondation de l'Hermitage, René Magritte, June-November 1987, p. 183, no. 43 (illustrated; illustrated again in color); Lausanne, Musée Cantonale des beaux-arts, La Femme et le Surrealisme, November 1987-February 1988, p. 271, no. 8 (illustrated in color).

Notes: Exercices spirituals is the second of two canvases that Magritte painted of a female nude, a large sphere, and seascape in the beginning of 1936. The significant differences in their respective compositions illustrate the diverse treatment that the artist gave to a single theme and his expertise in creating different connotations for juxtapositions of similar objects. The first version, entitled Baigneuse du clair au somber (Sylvester, no. 406; private collection), depicts a recumbent nude whose head, with closed eyes, is turned to a black sphere on the floor of a darkened room. The only light in the scene emanates from a framed painting of a beach and seascape on the wall behind her, which also gives the appearance of being a window to the outside.

Given the title's identification of the figure as a "bather," the painting appears to be a punning Surrealist interpretation of the genre made famous by Manet, Renoir, Cézanne and their contemporaries at the end of the 19th century, although Magritte's depiction of the seascape in the background suggests that her link to the outside world emanates from her dreaming unconscious rather than any actual proximity. The present scene, however, lends considerably more complexity to the image. Magritte has replaced the head of a now standing female nude with a light, shining sphere and placed her in an outdoor scene. This effect is heightened by a wall of anonymously rational architecture, which the artist has articulated with a radically slanted perspective, an ambiguous geometrical toy or set of weights, and a spectral, virtually camouflaged galleon sliding along the horizon. Although the nude woman seen here assumes a role similar to that in her initial incarnation (for which the artist's wife Georgette claimed to have posed), this once passive dreamer has now become a more confrontational and object-like presence. The viewer is no longer a detached and uninvolved witness to a mysterious and evocative dream, but is now faced with an challenging and perhaps even threatening hallucination.

The mannequin-like figure and hard-edged dreamscape seen here reflect the lasting impact of the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico's pittura metafisica on Magritte's oeuvre. Indeed, David Sylvester refers to Magritte's discovery of de Chirico's Le Chant d'amour, 1914 (fig. 1), as "one of the famous epiphanies in the hagiography of modern painting" (in op. cit., 1993, p. 61). Recalling the significance of this experience in his text La ligne de vie, Magritte stated: "This triumphant poetry supplanted the stereotyped effect of traditional painting. It represented a complete break with the mental habits peculiar to artists who are prisoners of talent, virtuosity and all the little aesthetic specialties. It was a new vision through which the spectator might recognize his own isolation and hear the silence of the world" (quoted in ibid.). Furthermore, the anonymity of present female figure and her relation to an industrial yet decidedly natural if not classicizing landscape reveals Magritte's knowledge of de Chirico's larger body of work, specifically his androgynous mannequin figures of the 1920s.

The title of the present painting is derived from the Ejercicios espirituales (1522-1524) of Saint Ignatius Loyola, which are prayer exercises designed to stimulate the mind, memory, will and imagination in order to better achieve communion with the divine. Although Magritte does not necessarily share the Christian message and spiritual intention of Loyola's text, he has set a similar task for himself, to instigate an alternate mode of thought in the viewer's mind through the suggestiveness of his imagery. He directs his viewers to exercise the powers inherent in their visual imagination and undertake a similar examination of consciousness, in order to arrive at a fuller understanding of human reality.

Portrait of Suzanne Spaak 1936

This portrait was painted for his sponsor, Claude Spaak. Spaak was a playwright, but had also been an active collector of Magritte's paintings for some time. In 1935, he made a semi-formal arrangement to allow Magritte to abandon commercial work and focus fully on his own artistic output. To this end, he provided the artist a monthly stipend, while also guaranteeing the paintings he produced. In addition to this, Spaak actively sought other sponsors for Magritte.

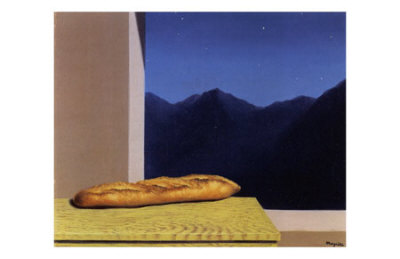

The Future (L'Avenir) 1936

Here Magritte implies that the future is a loaf of bread. Although Magritte was a socialist and professed atheist, I believe he was secretly curious about religion since he used religious imagery in several paintings. The bread of life...or at least a joke about it. The bread does seem to be rising to go out the window.

In Praise of Dialectics (Eloge de dialectique) 1937

This is a trompe l'oeil trick: what should be outside the window is really inside the window. Nice! This is one of the paintings Magritte did referencing the German philosopher Georg Hegel [Hegel's dialectics]. Magritte owned a French translation of Hegel's works and his philosophy of painting was organized in a similar way: By juxtaposing opposite images the mind seeks to resolve the conflict. This concept became intregal in Magritte's piantings and aptly illusttrated above: the outside is really the inside. [see also the 1958 Hegel's Holiday]

Here's a definition of "dialectic:" The Hegelian process of change in which a concept or its realization passes over into and is preserved and fulfilled by its opposite. The development through the stages of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis in accordance with the laws of dialectical materialism. Any systematic reasoning, exposition, or argument that juxtaposes opposed or contradictory ideas and usually seeks to resolve their conflict. The dialectical tension or opposition between two interacting forces or elements.

Spontaneous Generation (La Generation spoiltonee) 1937

Spontaneous Generation deals with the generation or duplication of images. Magritte did many paintings using multiple images including The Month of the Grape Harvest, The Golden Legend and his famous Golconda.

Portrait of Rena Schitz 1937

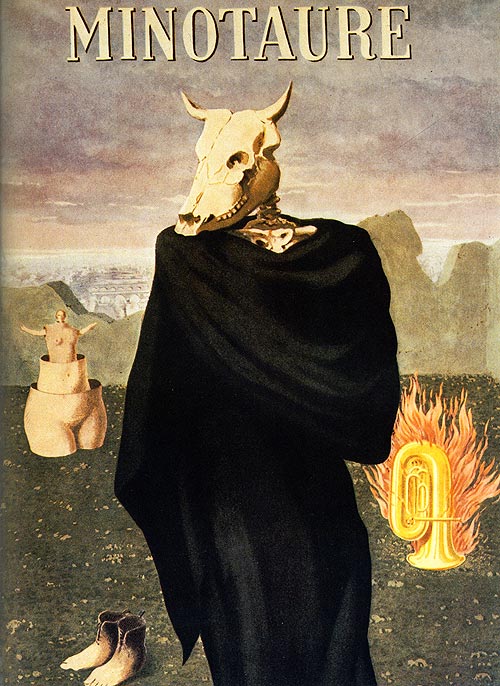

Magritte's Cover design for "Minotaur" issue 10. 1937

This cover feature three of the images for earlier paintings.

Portrait of Bazou and Pilette Spaak 1937

Bazou and Pilette are the children of Suzanne and Claude Spaak. Claude Spaak was a major patron of Magitte's art starting around 1925. Magritte also did portraits of Claude and Suzanne (above). Rene used Suzanne and Bazou's images for his "The Mathematical Mind."

Youth Illustrated (La Jeunesse illustree) 1937 oil

This uses some of Magritte's icons traveling down the path, the table is actually a pool table with pool cues leaning against it, after that there's a tuba and a bicycle. A similar scene was used in the above Portrait of Bazou and Pilette Spaak 1937. Another exact version, agouche was painted as well as a variant with the path going a different direction (Youth Illustrated II- below) as found in Portrait of Bazou and Pilette Spaak.

Youth Illustrated II (No date given)

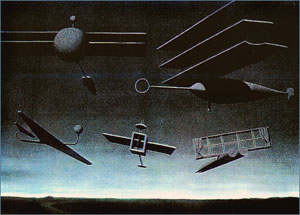

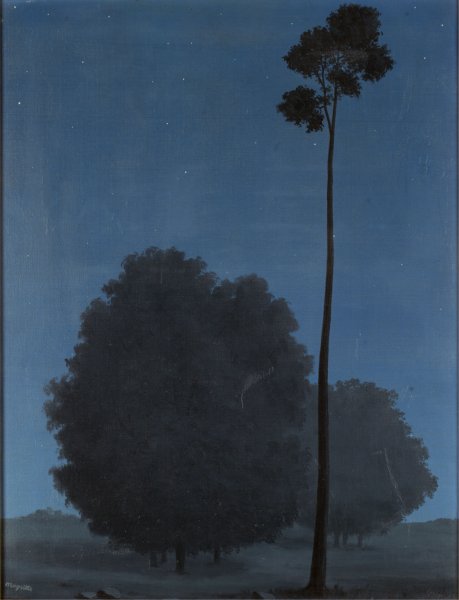

The Black Flag (Le Drapeu Noir) 1937

'The Black Flag surely refers to the German bombing of the small Spanish town of Guernica in April 1937 during the Spanish Civil War by twenty-eight German bombers, on April 26, 1937 during the Spanish Civil War. The attack killed between 250 and 1,600 people, and many more were injured (Wiki). Guernica was where the Nazis first tested aerial bombing on a civilian population; later it would be cities such as London and Coventry. Picasso's 1937 painting, Guernica, is perhaps the best known depiction.

In 1946 Magritte wrote fellow artist André Breton that the picture "gave a foretaste of the terror which would come from flying machines, and I am not proud of it." In contrast to artists who praised technology, Magritte was showing that machines have their darker side. Looking closely at the planes, one can see that they are made of a variety of strange shapes. The plane on the bottom right has a long, curtained window where its wings should be.

Georgette- 1937

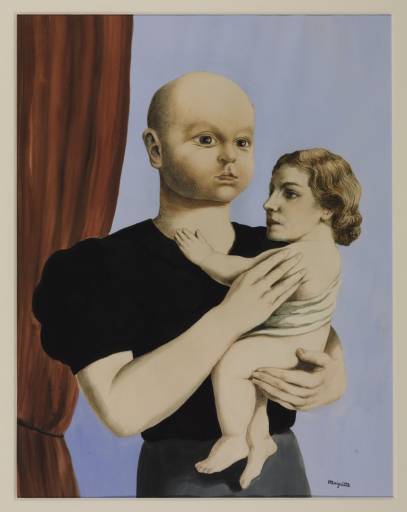

The Spirit of Geometry, Mathematical mind 1937

Representation- 1937

The Traveller Le Voyageur, 1937

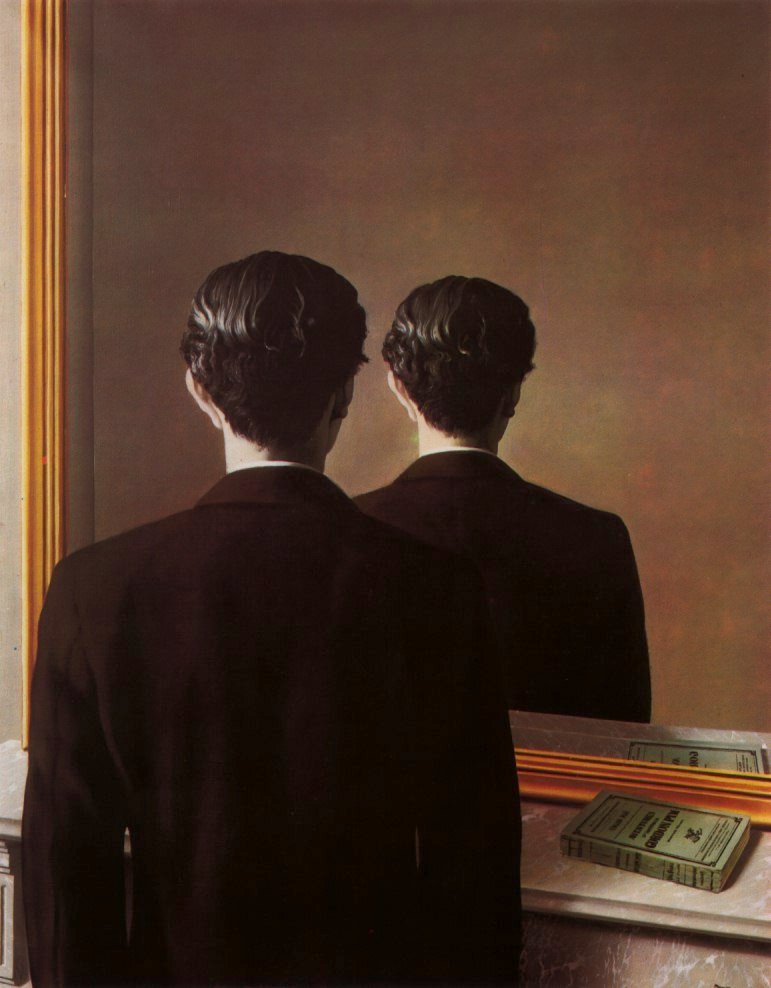

Reproduction Prohibited 1937

.%201937.jpg)

The Pleasure Principle (Portrait of Edward James) 1937

The White Race La Race Blanche, 1937

Magritte made several versions of "The White Race" which are based on Picasso's 1931 "Figures on A Sea Shore." Magritte likes to take pieces of the face and remove the rest of the face. He revisted this broken facial construction in the last years of his life, especially with his 1967 "The Age of Pleasure." He aslo did a bronze of "The White Race" that was executed in 1968 after he had died.

The White Race II La Race Blanche, 1937

Song of the Storm (Le chant de l'orage) 1937

The Song of the Storm shows a rain storm but the cloud is on the ground instead of in the sky.

The Red Model (Le Modèle Rouge) 1937

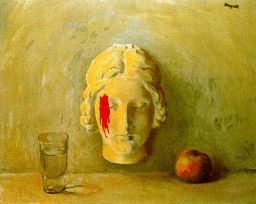

Memory 1938

Bel Canto, 1938

Domain of Arnheim 1938 oil on canvas

In 1938 Magritte painted a gouche and an oil of his Domain of Arnheim based on Edgar Allen Poe's story “The Domain of Arnheim:”

[From Poe:] "…no such combination of scenery exists in nature as the painter of genius may produce. No such paradises are to be found in reality as have glowed on the canvas of Claude. In the most enchanting of natural landscapes there will always be found a defect or an excess — many excesses and defects. While the component parts may defy, individually, the highest skill of the artist, the arrangement of these parts will always be susceptible of improvement. In short, no position can be attained on the wide surface of the natural earth, from which an artistical eye, looking steadily, will not find matter of offence in what is termed the ‘composition’ of the landscape. And yet how unintelligible is this! In all other matters we are justly instructed to regard nature as supreme. With her details we shrink from competition. Who shall presume to imitate the colours of the tulip, or to improve the proportions of the lily of the valley?"

The Domain of Arnheim may be Poe's greatest story. Poe himself held it in high esteem. He wrote, “ ‘The Domain of Arnheim’ expresses much of my soul.”

To Magritte The Domain of Arnheim represented the ideal landscape as expressed by Poe. Magritte also used the granite eagle on the mountain ridge in others works with different titles. The image of the mountain shaped like an eagle predates the “Domain of Arnheim” images, first appearing in “Le precurseur” (1936). The catalogue raisonné says, “The mountain may well have been based upon the upper two-thirds of a color reproduction of a photograph found among Magritte’s papers, something he certainly handled, as it bears a drawing by him on the verso.”

The “Domain of Arnheim” series:

1938 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 30 x 38 - whereabouts unknown

1938 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, oil on canvas

1944 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 33 x 46 - Caroline Pigozzi

1947 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 37.1 x 46.2 - Private collection, U.K.

1948 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 34 x 36 - Private collection

1949 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, oil on canvas 100 x 81 - Private Collection

1962 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, oil on canvas 146 x 114 - Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

1962 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper 35 x 27 - Private Collection

1962 - Le domaine d’Arnheim, gouache on paper, 25 x 19.2 - Eleanor Cramer Hodes

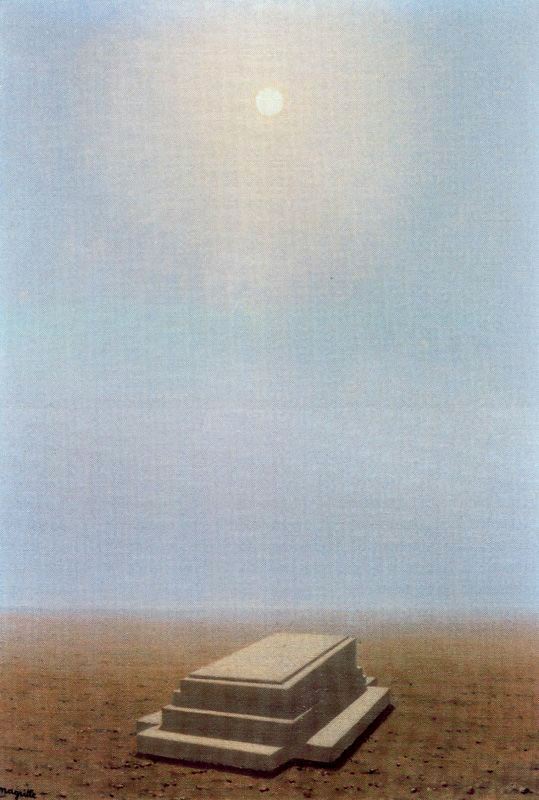

The Hereafter (L’Au-delà) 1938

Marches of Summer (Les Marches de l’Été) 1938

The Invasion L'lnvasion , 1938

Portrait of Space Lee Miller 1937

Elizabeth 'Lee' Miller, Lady Penrose (April 23, 1907- July 21, 1977) was an American photographer active in the sureralist movement from the late 1920 until the 1940s. Born in Poughkeepsie, New York in 1907, she was a successful fashion model in New York City in the 1920s before going to Paris where she became an established fashion and fine art photographer.

The Kiss (Le Baiser) 1938

Magritte saw Lee Miller's "Portrait of Space" at Roland Penrose's house in Hamstead, England in April 1938. ELT Mesens had introduced Magritte to them in Belgium and ELT was the first to publish Miller's "Portrait of Space" photo.

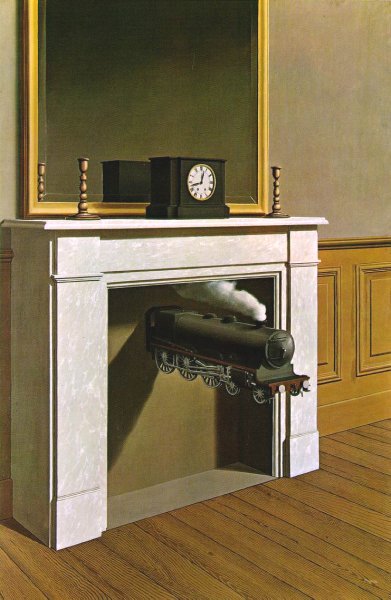

Time Transfixed 1938

The Witness- 1938

.jpg)

The present (Le présent) 1938-39

The Red model II 1939

Objective Stimulation 1939 Gouche

Magritte used the Venus de Milo form many times in the 1930s but here he gives it a new twist. He uses a smaller exact duplicate image superimposed to the original image.

Stimulation Objective No. 3 1939

Night Watch- 1939

The Ladder of Fire II (L'Échelle du Feu) - 1939

This is the second painting of the "Graditation of Fire" or "Ladder of Fire." Magritte compared this to the caveman's first discovery of fire. He said in a 1938 lecture, "The Ladder of Fire afforded me the priviledge of being acquainted with the feeling experienced by the first men who produced a flame by rubbing together two pieces of stone. In turn from a piece of paper, an egg and a key, I caused fire to spring forth." No lack of ego there Rene!

The Poetic World II (Le Monde Potique II) 1939

The Poetic World II is a variation of the 1931 Tempest I (see above). Once called "Composition with Clouds and Pate" this paintinf was part of the Edward James collection.

Glass House (La Maison de Verre) 1939

The House of Glass may be a portrait of Edward James although many people think it resembles Magritte and it certainly seems to be Magritte to me. This an example of seeing the back and front of an object or person at the same time. This was explored earlier in the 1926 Marriage at Midnight. The title glass denotes a transparancy or the ability to see through. Magritte used the same title for a different painting done in 1959.

The victory (la victoire) 1939, signed 'magritte' (lower right); signed, dated and titled '"LA VICTOIRE" MAGRITTE 1939' (on the reverse) oil on canvas 28½ x 21 1/8in. (72.5 x 53.5cm.)

My take on this painting is that it is a further exploration of Hegel's Dialectics, the door which is an object found inside is now an object found outside and mutates into the outside by attaching to the foreground and background by use of color. See also the 1939 painting-Poison, below. Here's some detailed info from Christie's:

Provedence: Claude Spaak, Choisel; Sidney Janis Gallery, New York; Mr and Mrs Albert Lewin, New York; sale, Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, 20 October 1966, lot 79; Acquired at the above sale by the present owner.