Magritte 1947-1948 "Fauve" or "Vache" period

In 1946 Magritte issued his manifesto Surrealism in full sunlight, saying, “We have neither the time nor the taste to play at Surrealist art, we have a huge task ahead of us, we must imagine charming objects which will awaken what is left within us of the instinct to pleasure.”

Although his "sunlit" Renior styled paintings began in 1943, all his work was not impressionist. At the start of 1947 Margritte was painting in both his realist style and his impressionist style. Some of his works (Intelligence; A Thousand and One Nights) were already headed toward more extreme colors. This fauve-inspired extreme style, closer to some of Van Gogh works, would accelerate in late 1947* [see 5th paragraph] when he was invited to hold his first solo exhibition in Paris at the Galerie du Faubourg in May 1948. He had waited twenty years to do a solo show in Paris and was resentful at the lack of appreciation that he felt the Parisian surrealists gave him. Magritte wrote at the time: "The paintings of Picabia should not make us dream of the revelations to be gleaned from coffee dregs, or prophesies..."

Then in 1947 Alexander Iolas, who became Magritte's principal dealer in the United States, successfully exhibited the artist's work in New York. Iolas then suggested that Magritte forget Renoir and sunlight to focus his output on images which overwhelmingly appealed to the public, like Treasure Island.

ELT Mesens helped organize the American exhibits with Iolas through a series of letters starting in 1946. Alexander Iolas (1907-1987) was born in Alexandria, Egypt, on March 25, 1907, to Andreas and Persephone Coutsoudis, who were Greek. In 1924, he went to Berlin as a pianist, and later became a ballet dancer who toured extensively with the Theodora Roosevelt Company and later with the company formed by the Marquis de Cuevas. In the 1940s, he ran a gallery in New York City promoting Max Enrst, Andy Warhol, Matta, Victor Brauner, Joseph Cornell, Yves Klein and Niki de Saint-Phalle. He also had galleries in Paris, Milan and Geneva. Although he promoted new work by unknown artists, Iolas was able to reassure the potential clients with his magnetic personality; his sharp dress and mischievous and sometimes irresistible charm.

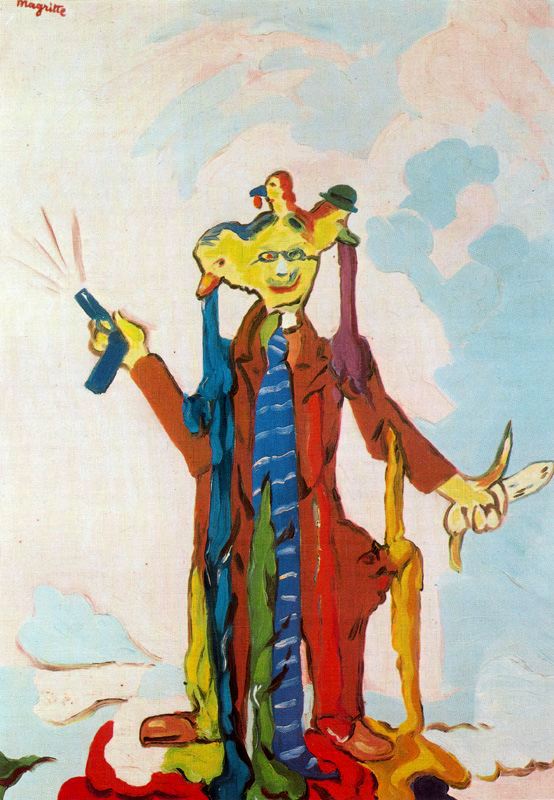

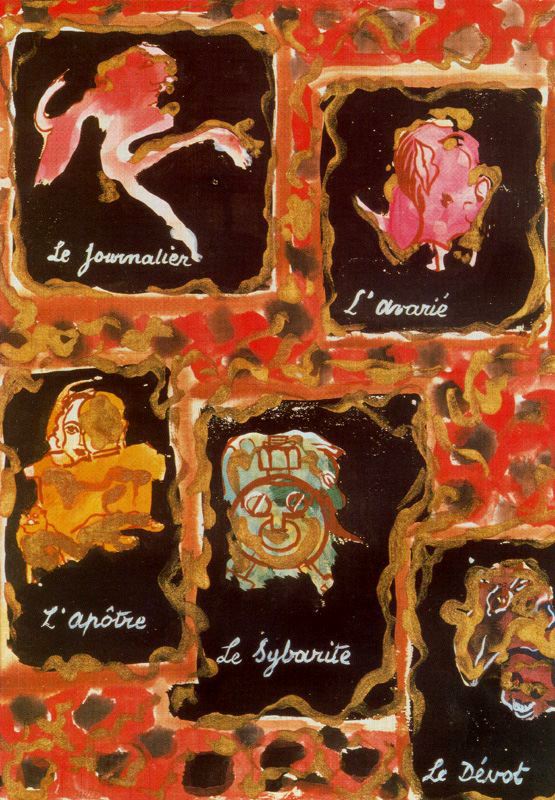

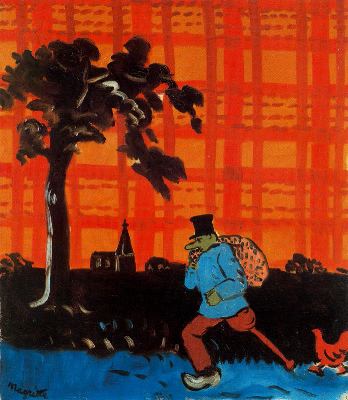

With some international recognition and success through Alexander Iolas, Magritte was not impressed by his invitation to hold his one man show at the Galerie du Faubourg, Paris. As a joke concocted by Magritte and his friends, Rene painted a series of hilarious pictures to exert a bit of revenge upon the Paris art world. Magritte experimented with a brash Fauve-inspired style in late 1947* dubbed "Vache" (literally, cow), which he premiered at an exhibition at the Galerie du Faubourg in Paris the next year. *[David Sylvester suggested that even though some of his Vache paintings were dated 1947 they were intentionally dated wrong so that Magritte could pretend that all the vauche paintings were not done deliberately for the Paris show, instead they were just part of a phase he started before he knew about the show.]

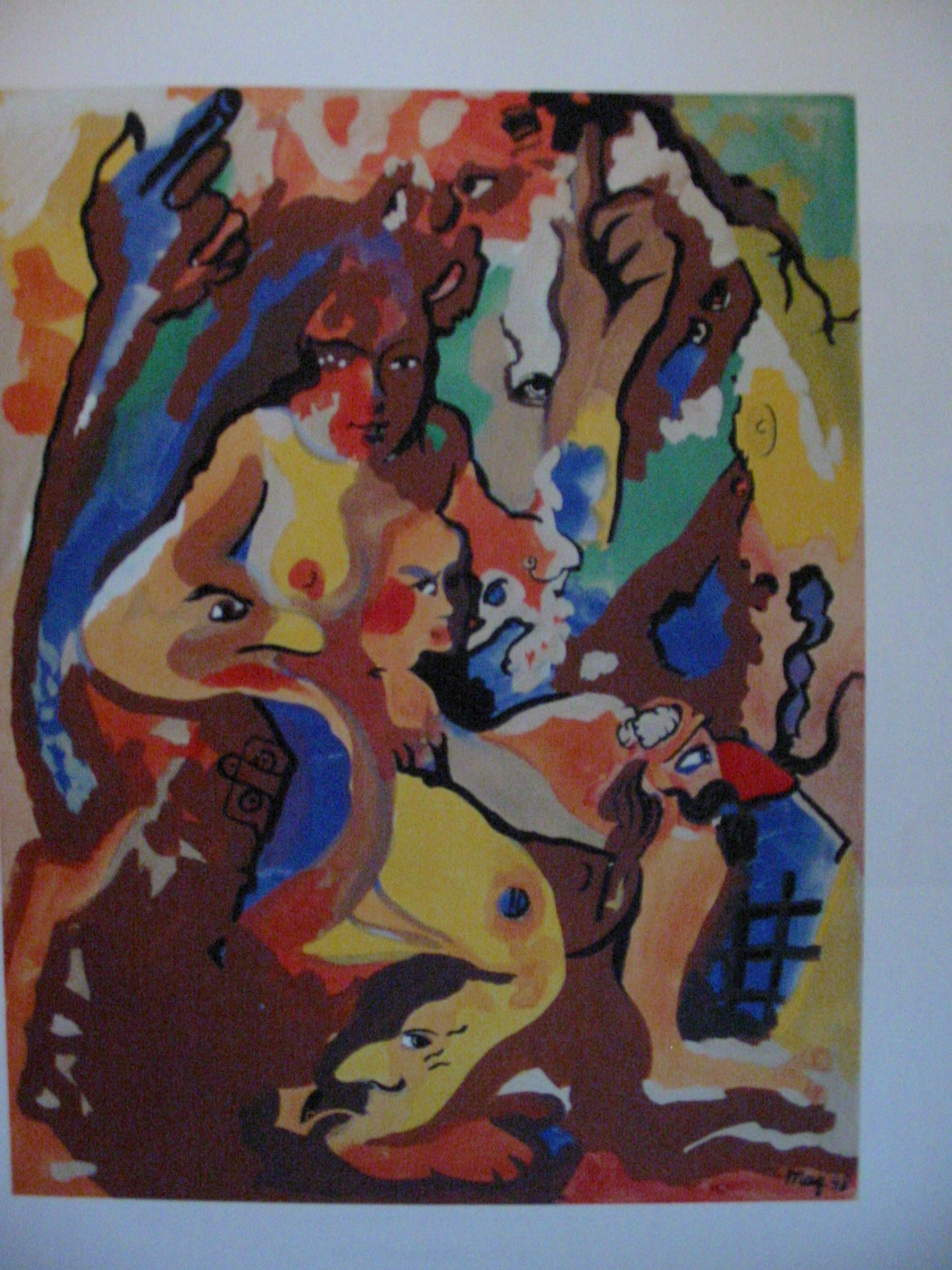

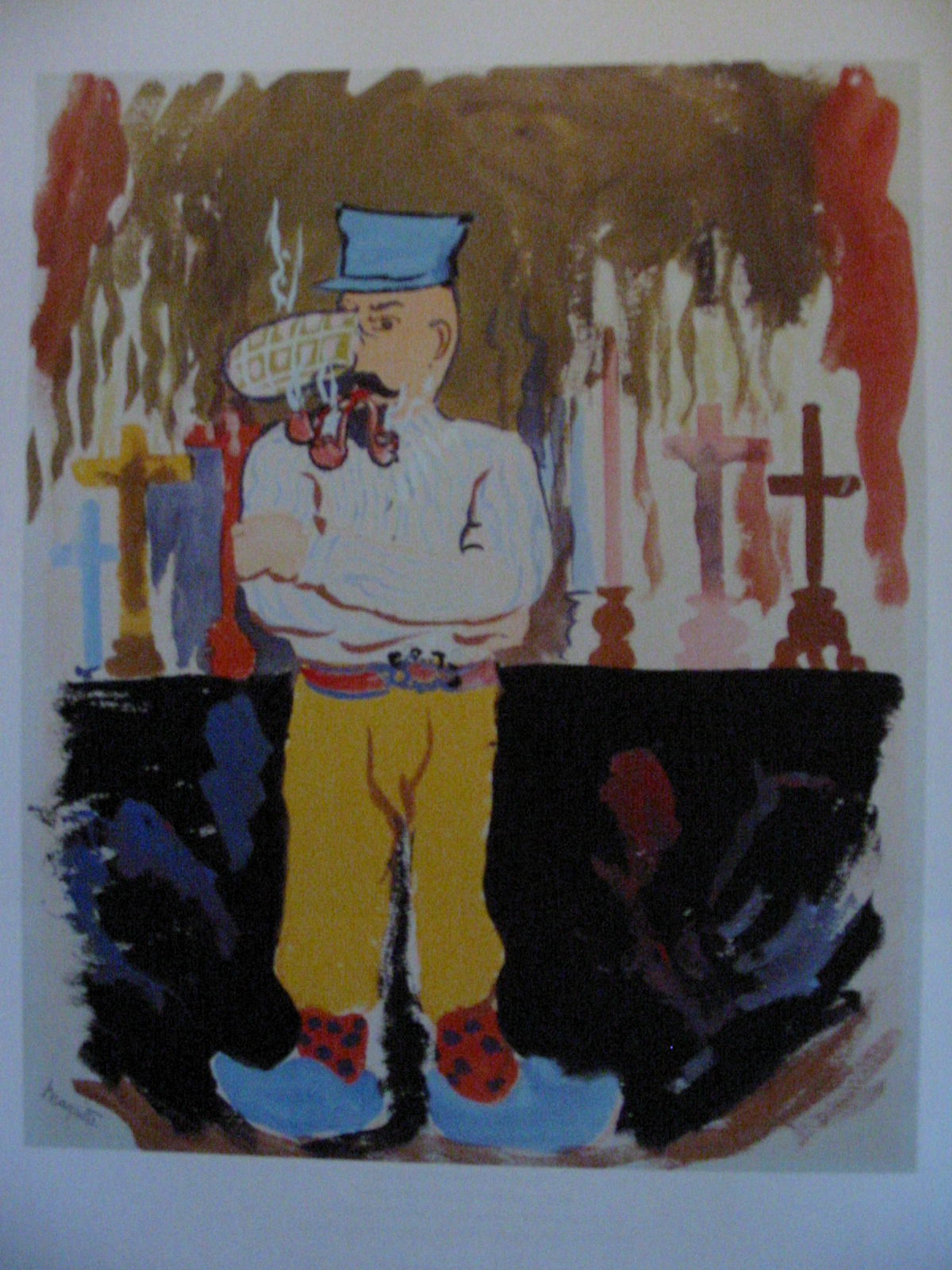

According to Bernard Marcadé: "In French, the term vache is used for an excessively fat woman, or a soft, lazy person. An unpleasant person is described as a peau de vache (cow-skin); amour vache (cow-love) refers to a relationship more physical than emotional. It thus treads a line between vulgarity and coarseness, and that is what characterises this set of paintings and gouaches, representing a radical departure from the painter’s neutral, detached style which had finally been accepted by Parisian Surrealist orthodoxy. Overall, the striking thing about these works is their garish tones, their exuberant, grotesque and caricatured subjects, all executed rapidly and casually in the name of a freedom from aesthetic and moral injunctions and prescriptions."

Louis Scutenaire came up with most of the titles and his wife, Irene Hamoir, contributed many of the ideas. Later on in the 1960s when cataloguing his own work, Magritte refered to the "vache" painting as his fauve style, a term he did not use in the 1940s and 1950 which he also called them, "the paintings of the doomed period."

Paris: May, 1948

"The exhibition was accompanied by a small catalogue with a preface by the poet Louis Scutenaire, bearing an evocative title (“ 9been putLes pieds dans le plat” – Putting one’s foot in it) and written in a slangy style, which is clearly in line with Magritte’s intentions. Moreover, Scutenaire would admit as much some years later: “The important thing was not to enchant the Parisians, but outrage them.” The triviality of the works actually wrong-foots Surrealist good taste. Both text and images are placed on a deliberately rustic and provincial register. “We’d been fed-up for a good long time, we had (been put), deep in our forests, in our green pastures.” Traditionally, the Belgians are seen as coarse peasants by the French, including the intellectuals." [Bernard Marcadé]

"The tone is set. Scut’ and Mag’ (their signatures, indicating their friendship and complicity) have decided to turn this exhibition into a kind of explosive manifesto against the arrogance and pedantry of the sycophants of the ideology advocated by André Breton. “The moment had come to strike a great blow,” Scutenaire would explain in retrospect. The two associates laid it on the line, The works shown in Paris joyfully mix comedy, viciousness and coarseness of the most scatological kind. In this respect they continue the visual counterpart to the three tracts that Magritte published in 1946 along with Marcel Mariën (The Imbecile, The Pain in the Arse, The Sod), in which one could already read a supreme contempt for all kinds of convention. Pictorial Content is probably the painting in the series which best allegorises Magritte’s desire to attack the pictorial practices with which he himself had engaged up until that point. It is no longer resemblance that is brought to the fore here, but an excess of distortion and a stridency of colour." Bernard Marcadé

I'm sure his Belgian group had a laugh at the outrageous paintings he produced for the show. Using the broad strokes and colors of Van Gogh he churned out a series of unsual paintings, some outrageous. The show in May at the Galerie du Faubourg was a failure, the French were not pleased. At the suggestion of his wife, Georgette and his principal dealer in the United States, Alexander Iolas, Magritte decides to abandon his "experiment" and return to his realistic style of the 1930s.

After signing a contract in 1948 with Alexandre Iolas, the New York dealer who would remained his agent until Rene's death, Magritte dedicated himself to producing the type of mysterious work that he would eventually lead to his international fame. Early in 1947 Magritte started his Cicerone series and his Shéhérazade series. His realistic style (encouraged by Iolas) was mixed with some impressionistic paintings like "The Sleepwalker" and "The Sage's Carnival' below. After the Paris exhibit in May Magritte returned to his realistic painterly style. He would occasionally produce impressionistic style paintings until his death in 1967.

Vache Gallery 1947-1948

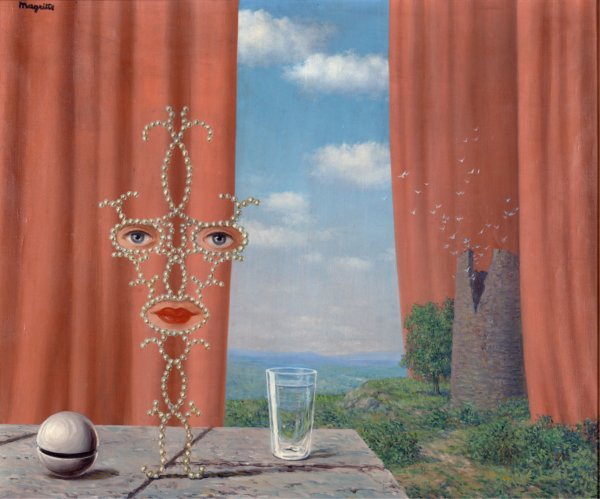

High Level Meetings (Les Grands Rendez-vous) 1947

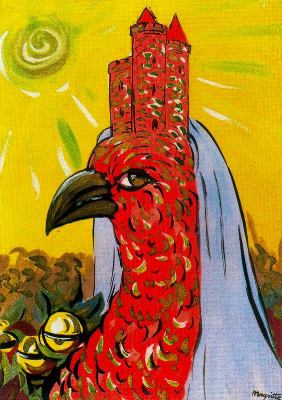

This facial image of the Persian queen, Shéhérazade, is repeated in several other paintings from this period including Shéhérazade (below) and The Liberator (below). The Shéhérazade image is based on Poe's short story, "The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade." The mysterious dark cave is similarly used in the 1928 Voice of Silence. Inside the cave are four various symbols [bird, cup, etc.] which are barely visible.

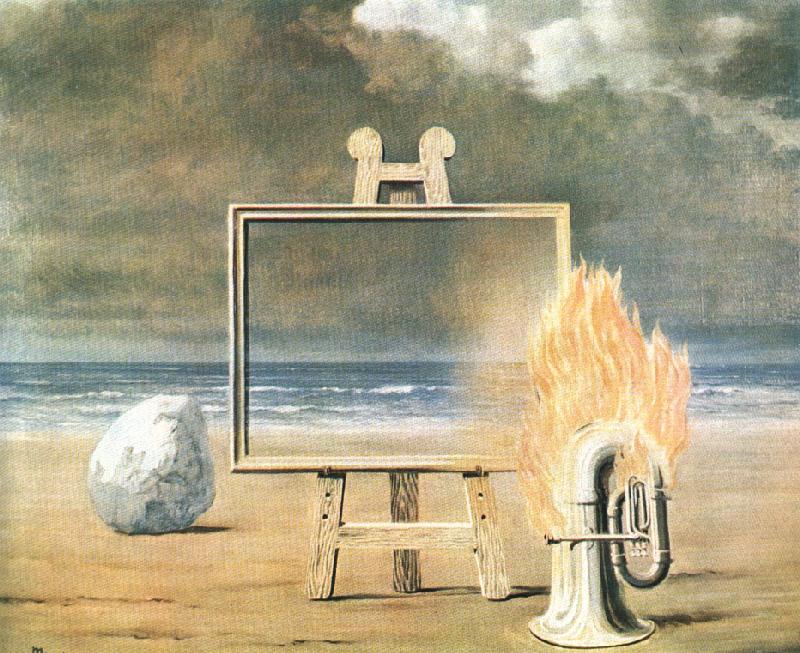

The Fair Captive (La Belle Captive) 1947, 53x66cm; 646x800pix, kb

This painting is the third version of The Fair Captive, differing from those of 1931 and 1935 which situated the easel in a landscape setting. It preceded by two years the series of works known by the title (The Human Condition) La condition humaine. In both series Magritte investigated the paradoxical relationship between a painted image and what it conceals. Magritte might have learned the painting within a painting from illustrations in A. Cassagne's Traité pratique de perspective (1873), a book used at the Académie Royale des Beaux Arts when Magritte was a student there. It was a rich field for investigation, as suggested by the number of variations on the idea. He surely saw De Chiricho's 1917 version of a painting within a painting, Great Metaphysical Interior.

In this present work, the easel, flanked by a boulder and a flaming tuba, is moved to a beach. Since the flames of the burning tuba leave a reflection on the 'canvas', we are brought again to the notion of the canvas both as a pane of glass which allows the spectator to 'see through' reality, and as a metaphor for painting as a window on reality, as with Duchamp's Large Glass (1923).

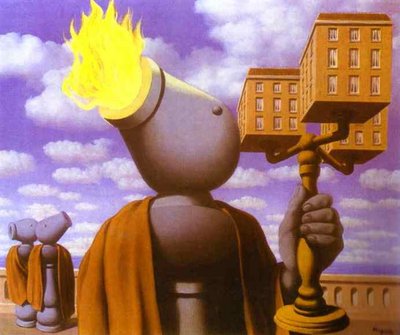

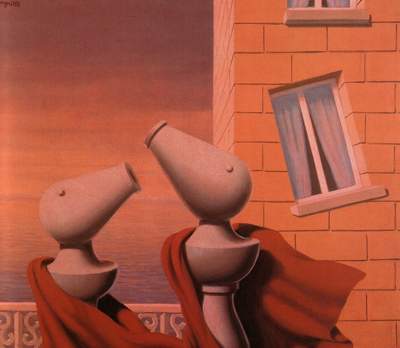

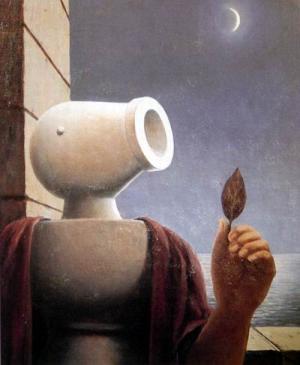

The Cicerone 1947

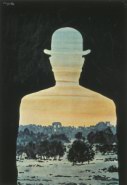

The cicerone, a giant bilboquet with human appendages and a bowled face, became a favorite icon during this time. Cicerone is an old term for a guide, one who conducts visitors and sightseers to museums, galleries, etc., and explains matters of archaeological, antiquarian, historic or artistic interest.

Philosophy in the Bedroom 1947

This paintings is a combination of two earlier paintings; Hommage to Mack Sennett and the Red Model series. The title is taken from

Marquis de Sade's Philosophy in the Bedroom (1795) which begins:

TO LIBERTINES: Voluptuaries of all ages, of every sex, it is to you only that I offer this work; nourish yourselves upon its principles: they favor your passions, and these passions, whereof coldly insipid moralists put you in fear, are naught but the means Nature employs to bring man to the ends she prescribes to him; hearken only to these delicious Promptings, for no voice save that of the passions can conduct you to happiness.

Lewd women, let the voluptuous Saint-Ange be your model; after her example, be heedless of all that contradicts pleasure's divine laws, by which all her life she was enchained.

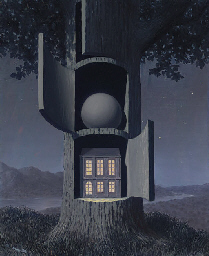

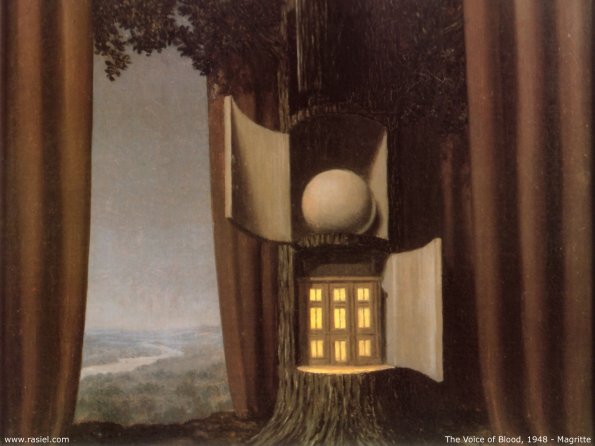

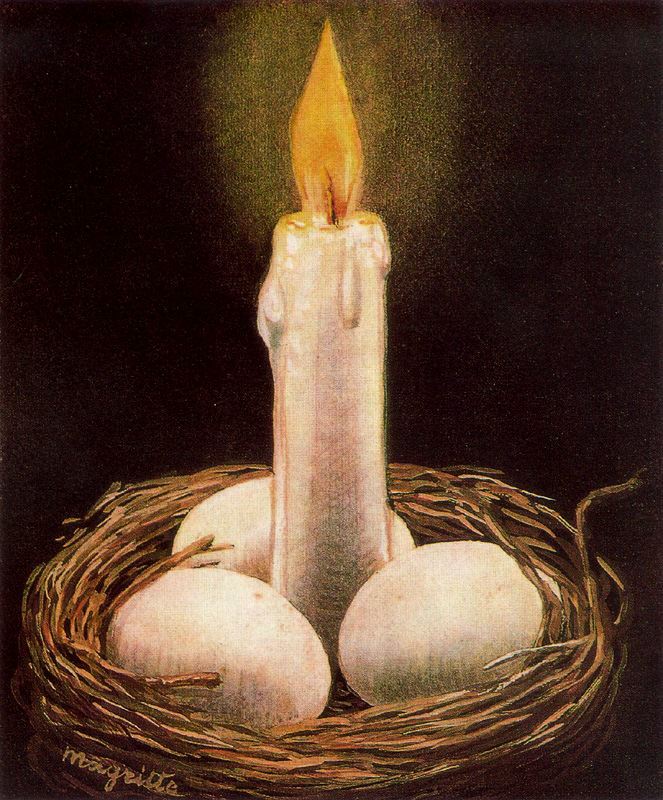

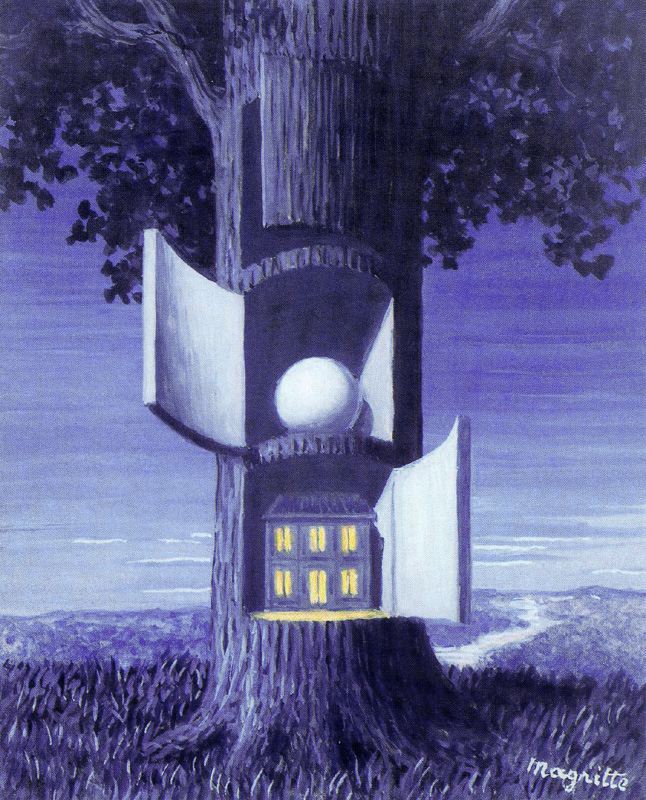

The Voice of Blood (La voix du sang) 1947 version signed 'Magritte' (lower left); titled and dated '"LA VOIX DU SANG"

1947' (on the reverse) oil on canvas, 25¾ x 21 3/8 in. (65.2 x 54.2 cm) Painted in 1947

Providence: Raymond Magritte, 1948. Arlette Dupont-Magritte (by descent from the above). Acquired from the above by the present owner, circa 2003.

Literature: J. Wergifosse and R. Magritte, Magritte, exh. cat., The Hugo Gallery, New York, May 1948. The Belgian Contribution to Surrealism, exh. cat., Edinburgh, Royal Scottish, August-September 1971, pl. 34 (illustrated in color). D. Sylvester, ed., René Magritte, Catalogue Raisonné, London, 1993, vol. II, p. 384, no. 625 (illustrated).

Exhibited: Brussels, Galerie Dietrich, Exposition Magritte, January-February 1948. La Louvière, Maison des Loisirs, René Magritte exposé, March-April 1954, no. 7. Charleroi, Salle de la Bourse, XXXe salon [du] Cercle Royal Artistique et Littéraire de Charleroi, including a 'Rétrospective René Magritte,' March 1956, no. 90. Brussels, Musée d'Ixelles, Magritte, April-May 1959, no. 39.

Brussels, Galerie Isy Brachot, Magritte: cent cinquante oeuvres: première vue mondiale de ses sculptures, January-February 1968, no. 79. Edinburgh, Royal Scotish Academy and Kongens Lyngby, Sophienholm, The Belgian Contribution to Surrealism, August-November 1971, no. 50. Paris, Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles, Hommage à Magritte, November-February 1985, no. 29.

Notes from Christie's: In La voix du sang and other works of the late 1940s, Magritte returned to the mysterious imagery and representational style of painting that had won him acclaim among the French Surrealists. The painter had spent the earlier portion of the decade producing parodies of Impressionism, but he now took the vocabulary that he had developed alongside his Parisian colleagues in the mid 1920s and applied it to his goal of upsetting the conscious ordering of conventional representation.

This mysterious image of a mighty, leafy tree transformed into a cylindrical cupboard with a white ball and illuminated house reveals the lasting impact of the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico's pittura metafisica on Magritte's oeuvre. Indeed, David Sylvester refers to Magritte's discovery of de Chirico's Le Chant d'amour, 1914 (fig. 1) as "one of the famous epiphanies in the hagiography of modern painting" (in op. cit., 1993, p. 61). Recalling the significance of this experience in his text La ligne de vie, Magritte stated: "This triumphant poetry supplanted the stereotyped effect of traditional painting. It represented a complete break with the mental habits peculiar to artists who are prisoners of talent, virtuosity and all the little aesthetic specialties. It was a new vision through which the spectator might recognize his own isolation and hear the silence of the world" (quoted in ibid.).

The present painting builds upon an idea that Magritte had initially established in L'arbre savant, 1935 (Sylvester, no. 384; fig. 2, private collection, Turin), which shows a rootless, dead trunk with four cabinets in an interior. The uppermost door is only slightly ajar, but the lower three are open, revealing a mass of metal wire, a pyramid, and a lit candle. In the present work, the scene is outdoors and nocturnal, and the tree, now robust and in full leaf, has three cupboards in its trunk. Despite these changes, Magritte preserved the provocative conflation of interior and exterior in the earlier work by reversing the relationship between the contained and the container. The artist may have based the unfolding bark doors of this tree on an illustration of cork harvesting that he found in the Larousse encyclopedia (fig. 3), one of his preferred sources of existing imagery. Magritte's colleague, the playwright Claude Spaak, has suggested that Magritte found this image in a chapter from Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) where she remarks that "one of the trees had a door leading right into it" (quoted in ibid., p 384).

Having established a new visualization of the compartmented tree with the present work, Magritte painted many subsequent versions that he also entitled La voix du sang; each of these works which retains this basic iconography with very slight modifications. In 1947, Magritte painted two gouaches of this scene (Sylvester, nos. 1235, 1236) and he produced a second oil painting with a crimson curtain, as well as two more gouaches in the following year (Sylvester, nos. 668, 1252, 1296). In 1953, the tree appeared alongside other iconic subjects in Magritte's repertoire such as his masked apples, bright blue skies, and the tree with an axe in an eight-sectioned cycle called Le domane enchanté of 1953 (Sylvester, no. 791) for the Casino Communale at Knokke-le-Zoute. Whereas Magritte cropped out the tree's canopy in these images, the fourth version in oil, painted in 1959 (Sylvester, no. 905; Museum moderner Kunst, Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna) expands the composition to encompass the whole tree, which he preserved in the fifth and final canvas done in 1961 (Sylvester, no. 928; private collection, Belgium).

The title of the present work translates as "Blood Will Tell," or alternately "The Call of Blood," which confers an ominous character onto the scene. The illuminated windows of the tiny house suggest an unseen and possibly nefarious activity. Magritte twice offered commentary on this work in 1948, yet his enigmatic words amplify the mysterious quality of the imagery. Addressing the scene in his text, Titres, Magritte states: "The words dictated to us by the blood sometimes appear foreign to us. Here, it seems to want to command us to open up magic riches in the trees" (quoted in ibid.). In an exhibition catalogue from the same year, Magritte refers to the tree as an enchanted creature, writing: "We could hear the hearts of the trees beating before the hearts of men" (quoted in ibid.). This cryptic subject matter is enhanced by an ambiguous sense of scale that is established in the sphere and house. The viewer must contemplate whether he can accept these two objects as a conventional sports ball and a dollhouse, especially if the house is possibly life-sized.

The grassy outcropping and mountainous landscape with a winding river and starry night sky may be a parodic quotation of the sublime and symbolic vistas that appear in Romanticist paintings such as Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818 (fig. 4). Recognizing the utility of such imagery for his own painting, Magritte commented: "I think the picturesque can be employed like any other element, provided it is placed in a new order or particular circumstances" (quoted in H. Torczyner, Magritte: The True Art of Painting, New York, 1977, p. 120). Friedrich explores the spiritualist connotations of awe before nature and their impact on the individual's inner world, underscoring the individual's quest to unmask an "original" truth. Whereas the cloaking "sea of fog" inspires a moment of personal revelation for Friedrich's mountaineer, Magritte's tree confronts the viewer with an unknowable mystery and reinforces the inadequacy of language, pictorial or otherwise. The Belgian artist equally played with hidden objects and a sense of the unknown, but he refutes the idea of absolute truth by making the instrument of concealment a depiction of precisely what it hides. In one of his best-known quotes, Magritte addresses this issue, stating: "My painting is visible images which conceal nothing; they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question 'What does that mean'? It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing either, it is unknowable" (quoted in ibid., p.70).

(fig. 1) Giorgio de Chirico, Le Chant d'amour, 1914. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

(fig. 2) René Magritte, L'arbre savant, 1935. Private collection.

(fig. 3) Illustration of a cork harvest from the Larousse encyclopedia.

(fig. 4) Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818. Kunsthalle, Hamburg.

The Mental Universe (L’Universe Mental) 1947

Night of Love 1947

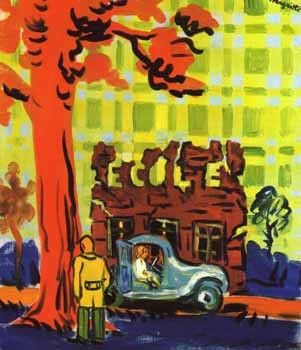

The House (La maison) 1947

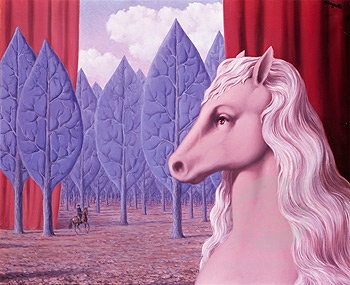

The Promised Land (La Terre promise) 1947

The cicerones are guides who lead us into Magritte's mysterious world, The Promised Land. Unfortunatey there's not much room in the Promised Land. Magritte uses magnification to place them in a room that's too small to move about freely.

The Sentimental Symposium (Le colloque sentimental) 1947

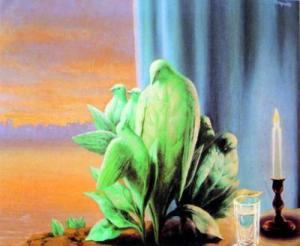

The Rights of Man (Les Droits de l'homme) 1947

The Rights of Man uses some of Magitte's favorite icons; the cicerone, the burning tuba (Discovery of Fire), the glass of water, the boulder and the leaf.

The Sleepwalker (Le Somnambule) 1947

The Sleepwalker is done in his "Sunlit" style he began using in 1943. He made several paintings with pipes during this period. Notice how many paintings from this period use the glass of water as a mysterious image.

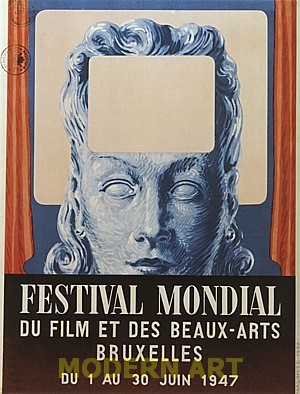

Poster for the festival Mondial du Film et des Beaux-Arts 1947

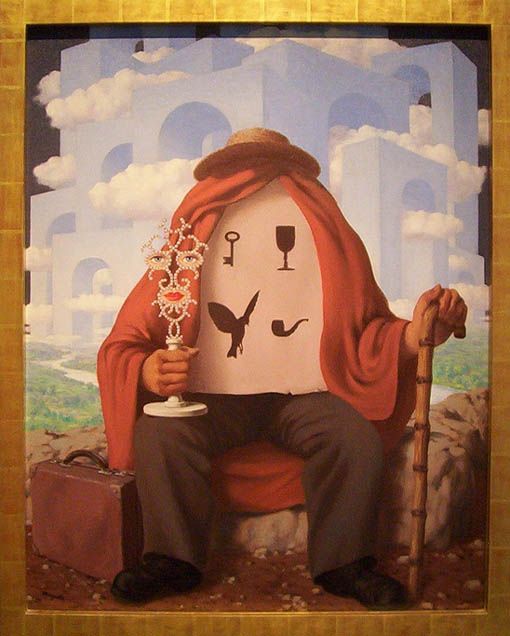

The Liberator 1947

The Liberator uses the same pose as Magritte's "Therapist" paintings. The liberator holds the facial image of the Persian queen, Shéhérazade, (see also High Level Meetings above) and his body is made up by the four icon found in the cave in High Level Meetings, the bird, the cup, the pipe, and the key.

The Sage's Carnival (Le Carnaval du sage) 1947, 25.6 x 19.5 in. / 65 x 50 cm

This same female figure became featured in some of Magritte's paintings around 1944 with the Sea of Flames. The female figure in not based on his wife Georgette but another female. Of some curiousity is the ghost in a white sheet. Magritte finds room to add two of his icon the glass of water and the loaf of bread.

The Serving of Fire (La Part du Feu) 1947

The woman serves the sleeping man (dying man) a cup with a carrot and an egg. Above them giant droplets of water are falling and there's a bilboquet with a candle at the foot of the bed.

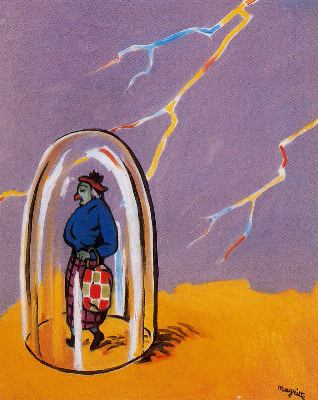

The Triumphant March- 1947

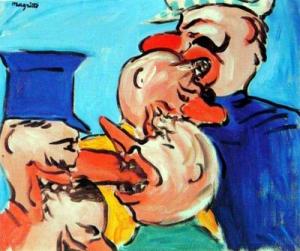

The is the first painting in my little gallery that is truly a "vache" painting. Some of the paintings are truly hilarious including this one. Many of the "vache" period paintings are becoming popular in their own right even though they were painted to be outrageous.

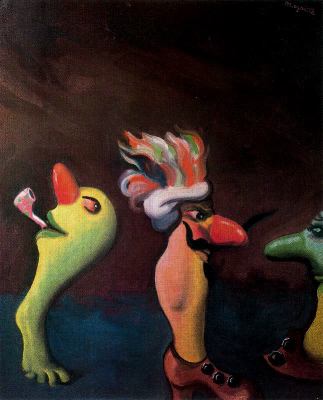

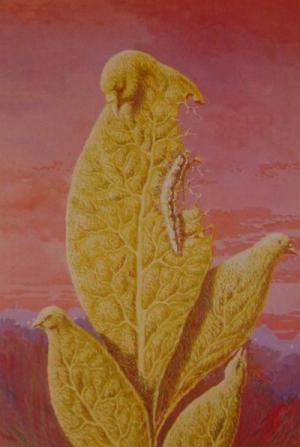

The Life of Insects (La Vie des Insectes) 1947

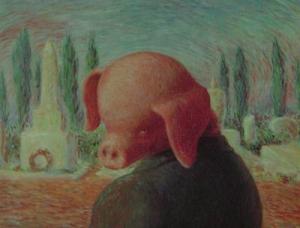

Lyricism (Le Lyrisme) 1947

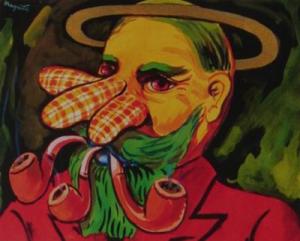

The Psychologist, 1947

The Pictorial Content (Le contenu pictural) 1947

The Tow Plug (El encededor) 1947

The Stage (L'Étape) 1948

The Ways and Means (Les Voies et Moyens) 1948

The Mountaineer, 1948

Titania, 1948 Gouche

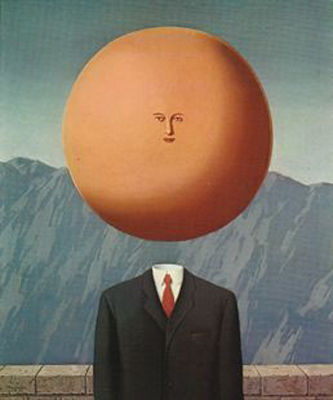

The Art of Living 1948

The Pope's Crime 1948

The Mark 1948

The Famine (La Famine) 1948

Pom'po pom'po pon po pon pon- 1948

The Cripple II- 1948

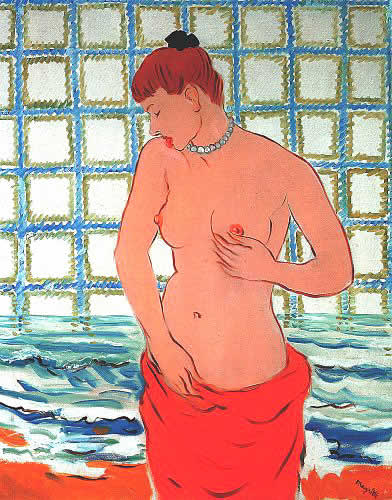

Lola de Valence 1948

The title of this work refers to Lola de Valence (1862) a (fully clothed) portrait painted by Manet (see below), and then immortalized in a quatrain by Charles Baudelaire which first appeared in the 1868 edition of Les Fleurs du Mal: “Entre tant de beautés que partout on peut voir, / Je comprends bien amis, que le désir balance; / Mais on voit scintiller en Lola de Valence / Le charme inattendu d'un bijou rose et noir.” Lola de Valence was the scene name of Lola Melea, the première danseuse of the dance company of Camprubi. It performed at the Porte Dauphine during the summer of 1862. Manet persuaded Camprubi to bring his dancers to the studio of his friend the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens during their leisure hours, and they posed for him there.

Lola de Valence (1862) Manet

Lola de Valence II- 1938

The Pebble (Le galet) 1948

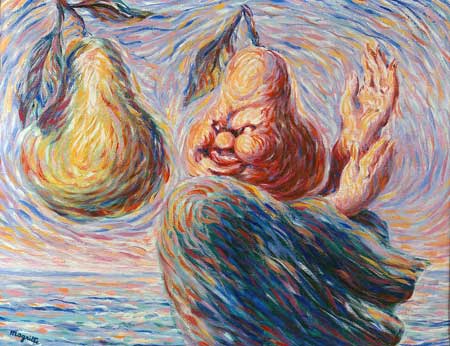

Depths of pleasure (La Profondeur du Plaisir) The 1948

The Archivist (El arcoiris) 1948

The Ellipse 1948

Jean-Marie 1948

Prince Charming (El príncipe encantador) 1948

Prince Charming-II 1948

A Stroke of Luck 1948

Freedom of Mind (La Liberte de l'esprit) 1948

The Drop of Water (La gota de agua) 1948

The Swallow of the Suburbs (L'Hirondelle des Faubourgs) 1948

Shéhérazade 1948

Shéhérazade is based on Edgar Allen Poe's short story, The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade which is a parody of the Arabian Nights tale of the beautiful Persian queen, Shéhérazade. The same image is found in High Level Meetings and the Liberator (se above).

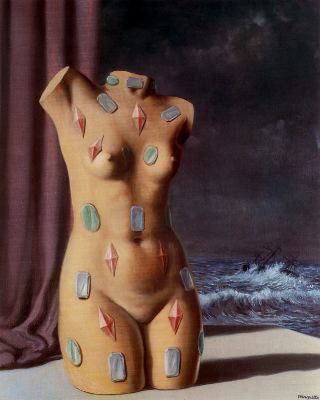

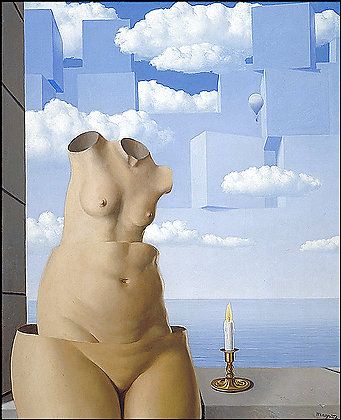

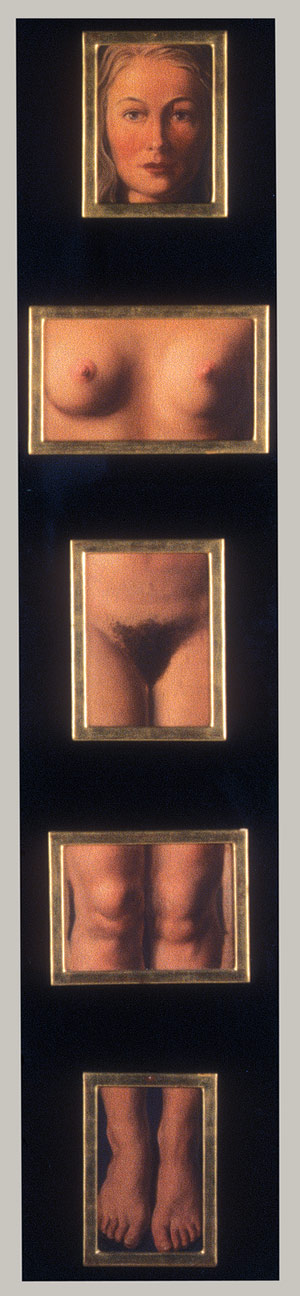

Delusions of Grandeur II 1948

This is essentially the same image found in Magritte's "Venus de Milo" series except it is sliced and stacked like Mental Complacency.

Marches of Summer (Les Marches de l'ete) 1948

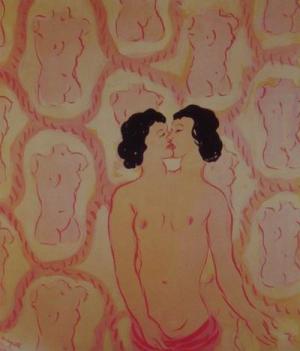

The Depths of Pleasure (Les profondeurs du plaisir) 1948

Magritte begins to use the iconic image of a glass of water. It appears in many paintings in the next several years.

"Voice of Blood" also know as "Blood Will Tell" Version II (La Voix du sang) 1948

Faulty Imagination 1948

The Cicerone II- 1948

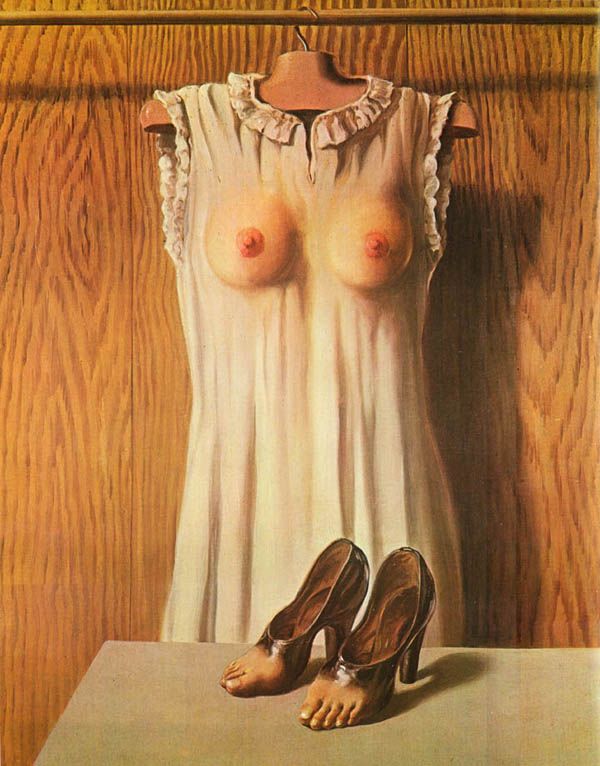

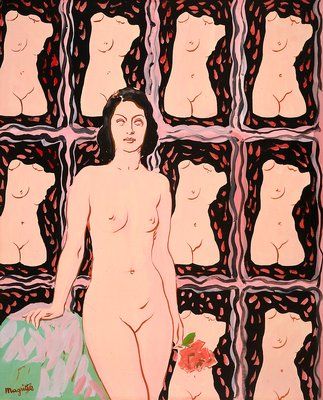

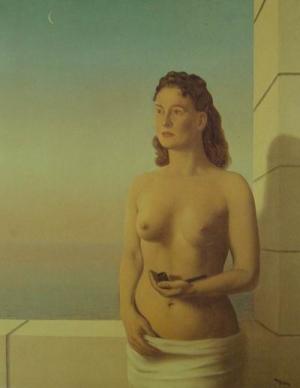

The Eternally Obvious II- 1948

Magritte painted the Eternally Obvious in 1930. Here he replaces Georgette with a younger model with firmer breasts

Flavor of Tears 2- 1948

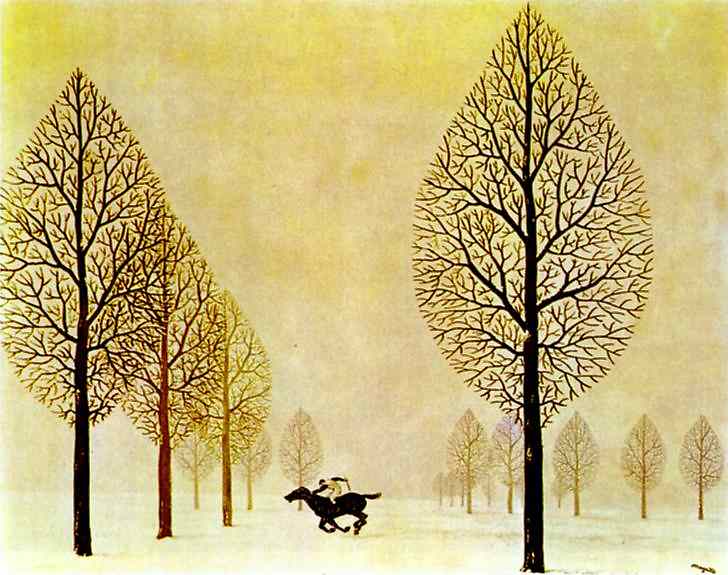

The Lost Jockey III 1948

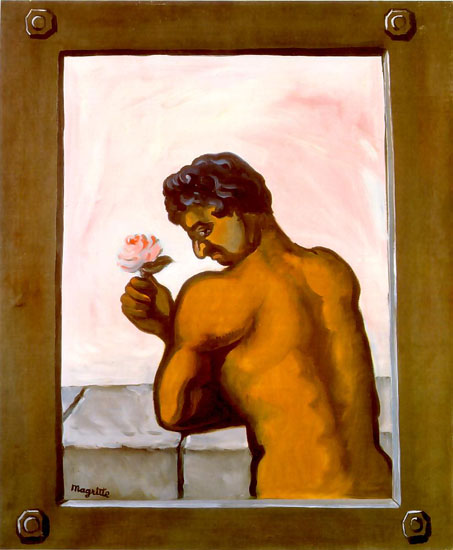

Encouraged by Alexander Iolas, his new art dealer, to paint versions of existing popular paintings, Magritte complies with this and teh following version of Memory.

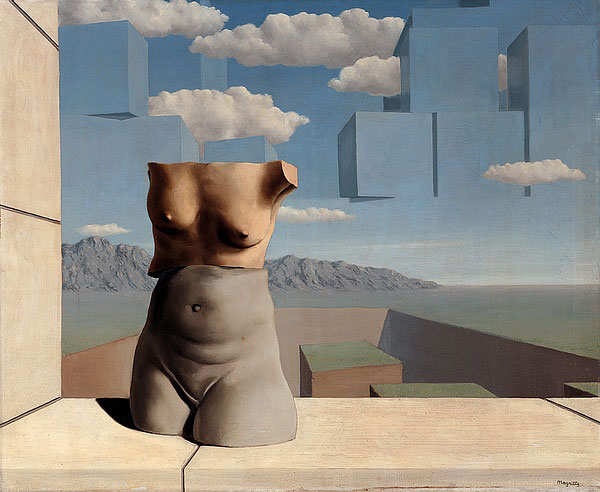

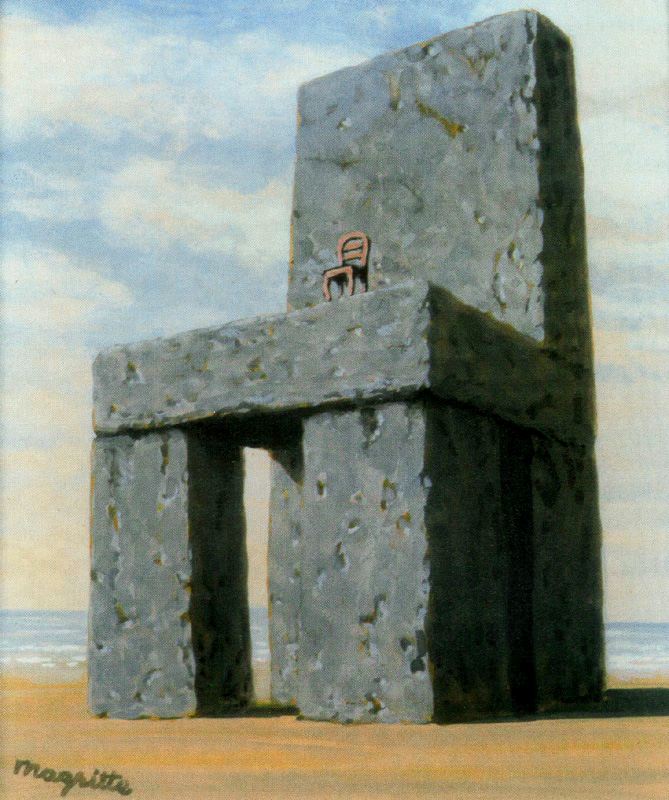

The Legend of the Centuries (La leyenda de los siglos) 1948

The first painting of two that Magritte made, this painting leads to his petrification series in the early 1950 and clearly has laid the foundation for his 1950 Art of Conversation series. Magritte would continuously experiment with magnification and petrification for the rest of his life (until 1967).

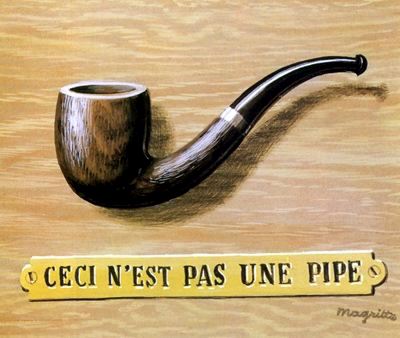

This is Not A Pipe 1948

The Voice of Blood II (La voz de la sangre) 1948 gouche

The tree is a favorite idea (see Version I and II above) and Magritte used it in different ways (see also Alice In Wonderland).

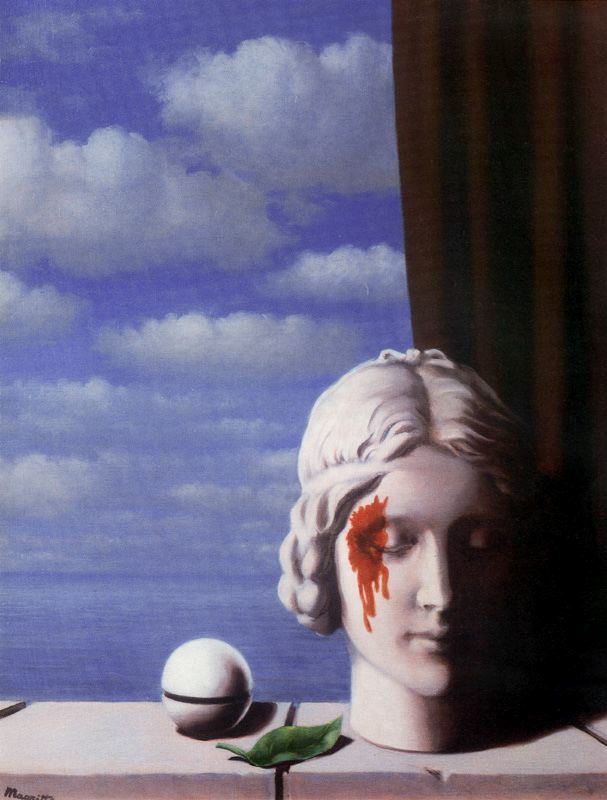

Memory III- 1948

Magritte did many versions of Memory. This, I believe, is the third. Sylvester assurts that this represents a plaster- of-paris face of a woman that drowned in the river. The same image is used in Deep Waters.

Pure Reason 1948

The Fair Captive IV La Belle Captive 1948 gauche

This fourth version of La Belle Captive is from 1948 and is painted in a more impressionist style.

The Art of Living (L’Art de Vivre) 1948

Magritte revisted this hilarious parody in the 1960s with an almost identical version.

God's Salon 1948

Around 1948 Magritte started experimenting with switching light and dark. He started his "Empire of the Light" series in 1948-49. Here he uses the opposite trick- it's a daytime scene with a dark night sky. The effect didn't work as well as his Empire of the Light. He uses this to better effect in his 1954 "Empire of the Lights" version (see 1954).

Magritte said, "I can imagine a sunny landscape under a night sky; only a god is capable of visualizing it and conveying it through the medium of paint, however. In the expectation that I will become one, I am dropping the project..."