Documents of Dada and Surrealism:

Dada and Surrealist Journals

in the Mary Reynolds Collection

New York

The same year Tzara introduced his review Dada in Zurich, related activities took place in New York. Not unlike Zurich, New York had become a refuge for European artists seeking to escape the war. For artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, the American city presented great potential and artistic opportunity. Soon after arriving there in 1915, Duchamp and Picabia met the American artist Man Ray. By 1916, the three men had become the center of radical anti-art activities in New York. While they never officially labeled themselves Dada, never wrote manifestos, and never organized riotous events like their counterparts in Europe, they issued similar challenges to art and culture. As Richter recalled, the origins of Dadaist activities in New York "were different, but its participants were playing essentially the same anti-art tune as we were. The notes may have sounded strange, at first, but the music was the same."[14]

The anti-art undercurrents brewing in New York provided an ideal climate for Picabia's provocative journal 391. Published over a period of seven years, 391 is the longest running journal in the Mary Reynolds Collection. The magazine first appeared in Barcelona in 1917, and was modeled after the pioneering journal 291, which was published under the auspices of the photographer and dealer Alfred Stieglitz.[15] Picabia was able to put out four issues of 391 in Barcelona with the support of some like-minded expatriates and pacifists.

391 2, ed. Francis Picabia (Barcelona, February 10, 1917), cover.

Although 391's corrosive spirit was only just emerging in these early issues, the anarchic attitude that would later define the magazine and its editor is already apparent. These first issues introduce, for example, a section devoted to a series of bogus news reports. As Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia recalled, this feature began as a mere joke and "quickly degenerated in subsequent issues into a highly aggressive system of assault, defining the militant attitude which became characteristic of 391."[16] These early issues include literary works by poet Max Jacob, painter Marie Laurencin, and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, as well as by Picabia, and feature cover illustrations of absurd machines designed by Picabia.

By the time Picabia took 391 to New York at the end of 1917, the magazine had assumed a decidedly assertive and irreverent tone. The New York editions of 391, issues five through seven, celebrate Picabia's nihilistic side and his love of provocation and nonsense. Buffet-Picabia had this to say about 391:

It remains a striking testimonial to the revolt of the spirit in defense of its rights, against and in spite of all the world's commonplaces...Without other aim than to have no aim, it imposed itself by the force of its word, of its poetic and plastic inventions, and without premeditated intention it let loose, from one shore of the Atlantic to the other, a wave of negation and revolt which for several years would throw disorder into the minds, acts, works, of men.[17]

Picabia's three New York issues feature contributions by collector Walter Arensberg, painters Albert Gleizes and Max Jacob, and composer Edgar Varèse.

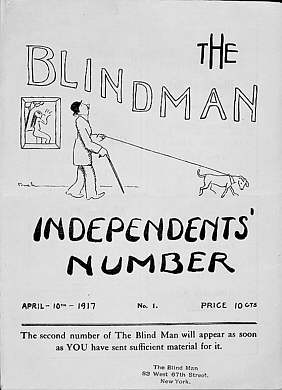

While Picabia was involved primarily with the group of artists surrounding Alfred Stieglitz and with the publication of 391, Duchamp made connections with Arensberg, through whom he became involved in the Society of Independent Artists. It was this organization, interested in sponsoring jury-free exhibitions, that gave Duchamp the idea for The Blind Man—a publication that would invite any writer to print whatever he or she wanted. The inaugural issue, published on April 10, 1917 by Duchamp and writer Henri-Pierre Roché, has submissions by poet Mina Loy, Roché, and artist Beatrice Wood. Emphasizing the informal editorial policies and uncertain future of The Blind Man, the front cover proclaims, "The second number of The Blind Man will appear as soon as YOU have sent sufficient material for it." When this hastily published first issue came out, the editors realized that they had forgotten to print the address of the magazine on the cover. To remedy this, a rubber stamp was created and used to imprint this information on the front cover of each issue.[18]

The Blind Man 1, eds. Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, and Henri-Pierre Roché (New York, April 10, 1917), cover.

Since Duchamp and Roché were not American citizens, and therefore faced possible conflicts with authorities, Beatrice Wood stepped forward to assume responsibility for The Blind Man. Because her father subsequently protested her involvement (due to the periodical's content), it was decided that rather than making it available to mainstream audiences through newsstands, The Blind Man would be distributed by hand at galleries.[19]

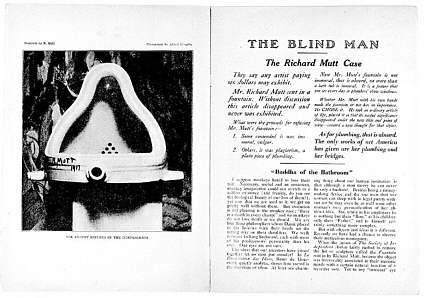

The Blind Man 2, eds. Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, and Henri-Pierre Roché (New York, May 1917), pp. 2–3.

The second issue of The Blind Man came out two months after the first,[20] following the opening of the Society of Independent Artists' 1917 exhibition and the rejection of Duchamp's infamous entry Fountain, a urinal that the artist signed with a fictitious name and anonymously submitted as sculpture. This issue features Stieglitz's photograph of Fountain and the editorial "The Richard Mutt Case," which discusses the rejection of Duchamp's entry. Also included in this issue were contributions by Arensberg, Buffet, Loy, and Picabia, among others.

While The Blind Man had caught the attention of the New York art community, a wager brought an early end to the magazine. In a very Dada gesture, Picabia and Roché had set up a chess game to decide who would be able to continue publishing his respective magazine. Picabia, playing to defend 391, was triumphant: Roché and Duchamp were forced to discontinue The Blind Man.[21]

Following the early demise of The Blind Man, Duchamp launched another short-lived magazine. Edited by Duchamp, Roché, and Wood, Rongwrong (May 1917) carries contributions by Duchamp and others within Arensberg's circle, as well as documentation of the moves from Picabia's and Roché's infamous chess game. Duchamp intended the title of the magazine to be Wrongwrong, but a printing error transformed it into Rongwrong. Since this mistake appealed to Duchamp's interest in chance happenings, he accepted the title.

The appearance of the journal New York Dada (April 1921) ironically marked the beginning of the end of Dada in New York. Created by Duchamp and Man Ray, this magazine would be the only New York journal that would claim itself to be Dada. Wishing to incorporate "dada" in the title of this new magazine, Man Ray and Duchamp sought authorization from Tzara for use of the word. In response to their tongue-in-cheek request Tzara replied, "You ask for authorization to name your periodical Dada. But Dada belongs to everybody."[22] In addition to printing Tzara's response in its entirety, this first and only issue also carried a cover designed by Duchamp, photography by Man Ray, poetry by artist Marsden Hartley, as well as several illustrations. As with so many self-published artistic journals, this first issue was neither distributed nor sold, but circulated among friends with the hope that it would generate a following. New York Dada, however, was unable to ignite any further interest in Dada. By the end of 1921, Dada came to an end in New York and its original nucleus departed for Paris, where Dada was enjoying its final incarnation.

Paris

Although Dada did not reach Paris until 1920, figures in the Parisian literary and artistic world had followed Dada activities either through Tristan Tzara's journal Dada or through direct communication with Tzara. Stifled by the restrictions of the war, they were drawn to Dada's revolutionary spirit and nihilistic antics. Writers Louis Aragon, Breton, and Ribemont-Dessaignes had in fact occasionally contributed to Dada since 1918, and were eagerly awaiting Tzara's arrival in Paris. The voice of Dada would soon be celebrated in Paris.

By 1920 most of the initiators of Dada has arrived in Paris for what was to be the finale of Dada group activities. Arp and Tzara came from Zurich, Man Ray and Picabia from New York, and Max Ernst arrived from Cologne. They were enthusiastically received in Paris by a circle of writers associated with Breton's and Aragon's literary journal Littérature. A special Dada issue of Littérature, with "Twenty-Three Manifestos of the Dada Movement," soon appeared to celebrate their arrival.[23] Stimulated by Tzara, this newly formed Paris group soon began issuing Dada manifestos, organizing demonstrations, staging performances, and producing a number of journals.

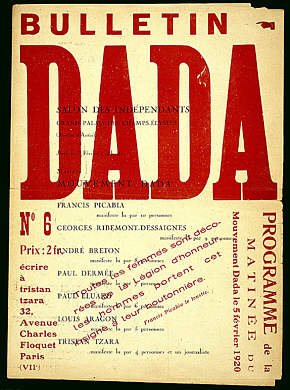

At the height of Dada activity in Paris, Tzara published two more issues of Dada. The first, issue number 6 (February 1920), also known as Bulletin Dada, appeared in large format and contained programs for Dada events, in addition to a series of bewildering poems and outrageous declarations, all presented in the fragmentary typographical style that Tzara had begun experimenting with in Zurich.

Dada 6 (Bulletin Dada), ed. Tristan Tzara (Paris, February 1920), cover.

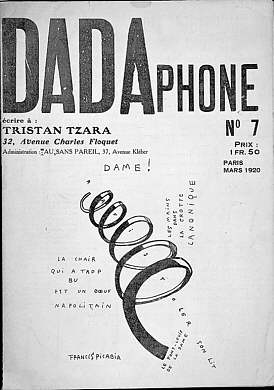

The many event announcements in this issue reflect the emphasis the Paris group placed on public performance. Contributors to the sixth issue of Dada indicate the range of artists who now aligned themselves with the Dadaists: Breton, Duchamp, Éluard, and Picabia are all featured in this issue. The last number of Dada (Dadaphone) came out in March 1920. This issue features photographs of the Paris Dada members and includes advertisements for other Dada journals and announcements for Dada events, such as exhibitions and a Dadaist ball.[24]

Dada 7 (Dadaphone), ed. Tristan Tzara (Paris, March 1920), cover.

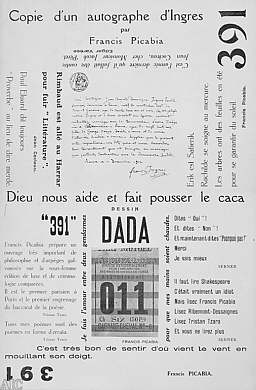

When Picabia joined the Dadaists in Paris in 1919, he too brought his journal with him. In Paris, between the years of 1919 and 1924, he published issues number nine through eighteen of 391 with contributions by such figures as writer Robert Desnos, Duchamp, Ernst, artist René Magritte, and composer Erik Satie. After producing four issues, Picabia temporarily suspended 391 in order to publish a new magazine he called Le Cannibale. Although more conservative in format than its predecessors, Le Cannibale has a provocative spirit and represents the height of Picabia's involvement in the Paris Dada group. After only two issues, (April 1920 and May 1920), however, Picabia abandoned Le Cannibale and resumed publication of 391. For issue number fourteen, Picabia created one of 391's most radical design layouts, using a striking combination of font sizes, type styles, and positioning of texts.

391 14, ed. Francis Picabia (Paris, November 1920), cover.

On the cover, he issued an iconoclastic attack on traditional art. Manipulating the autograph of the classicist artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Picabia inserted his first name in front of Ingres's. As "Francis Ingres," Picabia not only sought to undermine the position of canonical figures such as Ingres, but he also challenged the value placed on an artist's signature.

The next five issues of Picabia's journal reveal turmoil growing among the Dadaists and suggestions of a shift in Picabia's allegiance from Tzara to Breton. By issue number 16, it was clear that Picabia had left the Dada movement and was focusing on the activities of a newly forming group under the guidance of Breton. In the nineteenth and final issue of 391 (October 1924), he signed off as "Francis Picabia, Stage Manager for André Breton's Surrealism."[25]

The dissension evident in these final issues of 391 reflects the Littérature group's growing disillusionment with Tzara and his program. Despite his initial enchantment with Tzara,[26] by 1922 Breton had begun to have misgivings about the Romanian's directives for Dada. His nihilistic antics and anti-art proclamations, exhilarating at first, quickly became tiresome for Paris group members who essentially sought more meaningful and productive responses to their discontent. As he started to assert himself and his own program, Breton began to collide with Tzara. Unable to accommodate Dada to their enterprises, it was not long before Breton and the Littérature group denounced Dada and broke away from Tzara. In one issue of Littérature Breton wrote:

Leave everything.

Leave Dada.

Leave your wife, leave your mistress.

Leave your hopes and fears.

Sow your children in the corner of a wood.

Leave the substance for the shadow....

Set out on the road.[27]

On another occasion, he declared, "We are subject to a sort of mental mimicry that forbids us to go deeply into anything and makes us consider with hostility what has been dearest to us. To give one's life for an idea, whether it be Dada or the one I am developing at present, would only tend to prove a great intellectual poverty."[28] Soon the world would learn of Breton's developing ideas, and the flag of Surrealism would be raised.