The European Avant-Guarde

By Sophie Taeuber (Morton Livingston Schamberg; Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven; Johannes Baader; Johannes Baargeld)

Europeans at the turn of the century were witness to an incredible outpouring of ideas with regard to art and theory. Most of the Surrealists were active members of one or several artistic movements before and, at times, during their association with Surrealism. Most were well informed of the variety of concepts and beliefs swirling about them. From this state of flux, Surrealism precipitated its aesthetic and many of its techniques.

Cubism and Picasso

Cubism is often considered antithetical to Surrealism. The broken planes of early Cubism are related to an analytical tradition that concerns itself with a visual and systematic breakdown of the object and its restructuring. It is part of the broad current of structural concerns Surrealists rejected as irrelevant. But for Breton "that ridiculous word 'cubism' can never conceal from me the enormous significance of that sudden flash of inspiration" that occurred in Picasso between 1909 and 1910.

In Picasso Breton saw an individual so protean he broke rules and was liberated from categories and labels through his restless sense of internal vision, seeing then bringing into existence things none but poets had envisioned. It was the path and the broad accomplishment that interested Breton. In building this case Breton felt that he was also building the case for Surrealism to avoid and operate outside of systems.

Cubism set the pace for much of what is considered modern art in the early 1900s. But most of those footsteps were not applauded by the Surrealists since they were seen as servile and not as creative. Precisely where the line was to be drawn was problematic since Breton, among others, used as his requirement for art criticism an inner psychic vibration that one simply could sense. He dismissed many artists, well-known Cubists among them, for "propagating utterly superficial values." In many ways, Breton sounds surprisingly like an Expressionist because both movements placed primary importance on the interior state.

Pablo Picasso: Woman Playing the Mandolin 1909

The crisp edges and analytic attitude of early Cubism seems opposed to the Surrealist dream world, but Cubism was admired as a movement that heralded the crisis of the object, and Picasso was Breton's favorite artist.

German Expressionism

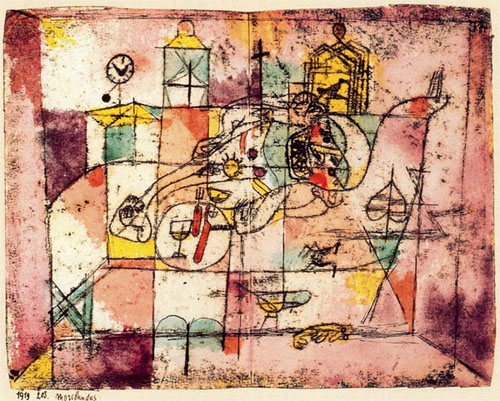

Paul Klee, the Swiss-born artist, was a member of the German Expressionist movement. He never joined the Surrealists but was well known to and showed with them. Breton placed him on his short list in 1924 as one of the few he could call "Surrealist," and as late as 1941 Breton recounted that Surrealism owed a debt to Klee's use of "automatism." Automatism—the free flow of associations—was advanced by Breton as the single most important key to the definition of Surrealism, a path to the inner psyche. Klee had been employing automatism since about 1914, when he would close his eyes, turn his mind inward, and automatically doodle on a pad to initiate an image.

Beyond specific influences, Expressionism was a seminal art movement which argued that the source of art was inward. However, the Expressionists referred more to inner "feelings" and these differed from the inner "psychic" sources desired by the Surrealists. The two movements shared an insistence on art deriving from some internal compulsion but the Surrealists argued more for a pathological condition beyond control, rather than an expression of will or spirit. Any artist who lost their compulsion, according to Surrealist stricture, lost their path.

Paul Klee Moribundus

Italian Futurism (1909-16)

Futurism, founded by the poet Marinetti in Italy in 1909, was the most aggressive of the pre-war avant-garde art movements. The Futurists sought art forms that would embody the energy and dynamism of the new century, propelling Italy out of its classical past and into the future of machinery, speed, and violence. Andre Breton often referred to Futurism in the same breadth as Cubism, as one of the two movements that effectively challenged the past concepts of the "object," placing it in "crisis." The message was simply that Surrealism in the 1920s would take on the next step in the process initiated by Cubism and Futurism.

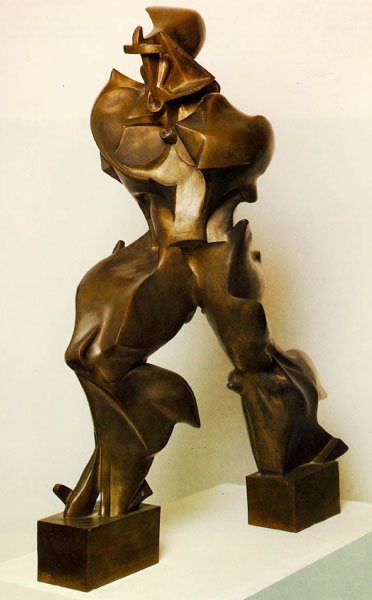

The Futurist painters married bright colors to the planes of Cubism and set them in newly dynamic relationships, using movement and light to destroy the static quality of the material world. In its sculptural form, Umberto Boccioni's bronze Unique Forms of Continuity in Space was a literal attempt to first dissolve then extend material form through "lines of force" and into a fusion with the world around it.

Whether these lines of force were painted or sculpted, composed of words or of music, they were to be set free with the velocities of modern life to merge art, spectator, and life into a new complex whole. The Futurist lines of force were not simply a representation of stop-action or cinematic parallels, although photography and the new medium of film were of important influence, as they would come to be for Surrealism. They were also intended to give form to what is sensed rather than merely seen— the future unfolding of the object simultaneously with this time, the real as a mixture of the seen, the remembered, and the sensed. The desire to communicate on a more fundamental level in a new understanding of the real made both the Futurist and the Surrealists self-proclaimed "primitives of a new and completely transformed sensibility."

The wide range of parallels included the aggressive and the bombastic quality of their declarations and manifestoes. Both movements were founded through passionate beliefs in poetic sensibilities, the prime importance of individual creativity, and an almost absolute sense of personal freedom and liberation. Marinetti developed the concept of "words set free" (parole in liberta), the next step after free verse, to free words from the constraints of syntax and create a more instinctual level of communication. This included poems composed anarchistically, distributed across the page in a variety of type fonts, sizes, and densities. Their pell-mell barrage on the senses was deliberate, part of the principles of "simultaneity" and "brutism."

Professed, if not practicing, anarchists, the Futurist believed in violence and the brutalities of raw energy to disrupt and divert life from Italy's "cult" of the past into a new society. Central was the fusion of art to life, leading then, as it still does today, to the use of public performance and moments. Short performances that were non-narrative, often surprising, and always disruptive and shocking were developed. Sharp, explosive sounds such as a gunshot were accompanied with bursts of light, screams, and sudden, unexplained events, which included overselling tickets and physical disruptions in the audience. The audience was to be "brutalized" by input and shocked out of normalcy, precisely what Marinetti was attempting to initiate with poetry.

This was the perfect avant-garde product, picked up by the Dadaists, then by the Surrealists. Shocking the middle class became and often remained the byword of the new. It had political meaning, however, among the class-oriented Europeans throughout the early twentieth century.

Futurist Manifestos

The Italian Futurists (1911) claimed an anarchistic attitude toward the modern world that fueled the ideas in Dada, and eventually affected Surrealism. Boccioni's striding figure throws out "lines of force" to merge form and art with its environment.

Umberto Boccioni: Unique Form of Continuity in Space 1913

International Dada

The Dada movement was the birthing field for Surrealism. The name was essentially meaningless and the lack of meaning was a major strategy. Randomness was one of their purposive values; by definition it cannot be predicted, thus only the act is codified. The Dada movement refined many of the basic ideas, established the early membership, and eventually became the opposing force to the Surrealists. Francis Picabia, a member of both groups, wrote in 1925 that Breton's surrealism was simply Dada disguised as an advertising balloon for the firm Breton & Co.

Dada was energetic activity organized as a spontaneous gesture against the insanity of a worldwide war. Dada advertised itself as without value but manifested outrage because values had been violated. If rationality brought humanity to the level of world war, argued the Dadaists implicitly, then the true name of reason was insanity. And they would demonstrate the true nature of life: in the leveling of art and life, the reliance on the energies of creativity hurled like a chair into the face of conformity, and the overall program of random yet purposeful destruction, Dada resembled the program of the Futurists and motivated the Surrealists.

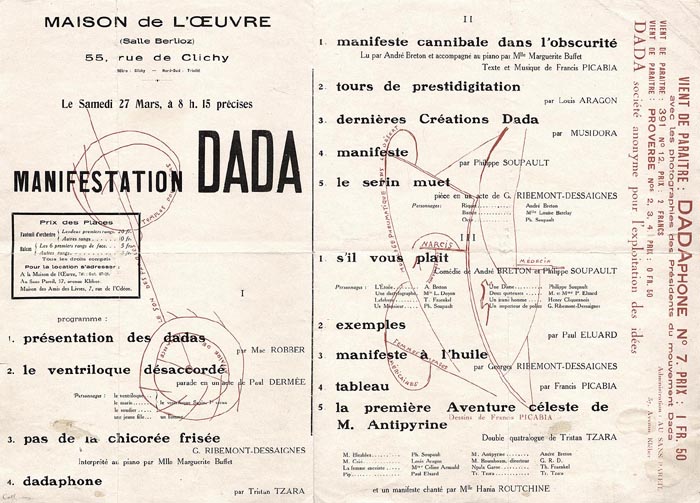

Dada Handbill

Here the ur-DADAs (Tristan Tzara, Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Jean Arp, Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck and others) experimented frenziedly, at first scandalizing audiences and eventually gaining worldwide momentum as an artistic force. By the mid-1920s, DADA retreated into relative obscurity because, as the DADAists themselves proclaimed, “DADA is nothing.” But the form never died and has been resurrected and riffed on by Todd Rundgren, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Julian Beck, Jerome Rothenberg, Janet Coleman and David Dozer, Ira Cohen, Valery Oisteanu, Rebecca Krell, and many others.

Photo by Mike Sullivan

Dada (Encyclopaedia Britannica)

(French: “hobby-horse”), nihilistic movement in the arts that flourished primarily in Zurich, New York City, Berlin, Cologne, Paris, and Hannover, Ger. in the early 20th century. Several explanations have been given by various members of the movement as to how it received its name. According to the most widely accepted account, the name was adopted at Hugo Ball's Cabaret (Café) Voltaire, in Zurich, during one of the meetings held in 1916 by a group of young artists and war resisters that included Jean Arp, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, and Emmy Hennings; when a paper knife inserted into a French–German dictionary pointed to the word dada, this word was seized upon by the group as appropriate for their anti-aesthetic creations and protest activities, which were engendered by disgust for bourgeois values and despair over World War I. A precursor of what was to be called the Dada movement, and ultimately its leading member, was Marcel Duchamp, who in 1913 created his first ready-made (now lost), the “Bicycle Wheel,” consisting of a wheel mounted on the seat of a stool.

The movement in the United States was centred at “291,” the New York City gallery of Alfred Stieglitz, and the studio of the Walter Arensbergs, both wealthy patrons of the arts. There Dada-like activities, arising independently but paralleling those in Zurich, were engaged in by such artists as Man Ray, Morton Schamberg, and Francis Picabia. Both through their art and through such publications as The Blind Man, Rongwrong, and New York Dada the artists attempted to demolish current aesthetic standards. Travelling between the United States and Europe, Picabia became a link betweenthe Dada groups in New York City, Zurich, and Paris; his Dadaperiodical, 291, was published in Barcelona, New York City, Zürich, and Paris from 1917 through 1924.

God 1917 by Morton Livingston Schamberg (USA, 1881–1918) and Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (German, 1874–1927)

In 1917 Hulsenbeck, one of the founders of the Zurich group, transmitted the Dada movement to Berlin, where it took on a more political character. Among the German artists involved were Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Hoch, George Grosz, Johannes Baader, Hulsenbeck, Otto Schmalhausen, and Wieland Herzfelde and his brother John Heartfield (formerly Helmut Herzfelde, but Anglicized as a protest against German patriotism). One of the chief means of expression used by these artists was the photomontage, which consists of fragments of pasted photographs combined with printed messages; the technique was most effectively employed by Heartfield, particularly in his later, anti-Nazi works (e.g., “Kaiser Adolph”). Like the groups in New York City and Zurich, the Berlin artists staged public meetings, shocking and enraging the audience with their antics. They, too, issued Dada publications: Club Dada, Der Dada, Jedermann sein eigner Fussball (“Everyman His Own Football”), and Dada Almanach. The First International Dada Fair was held in Berlin in June 1920.

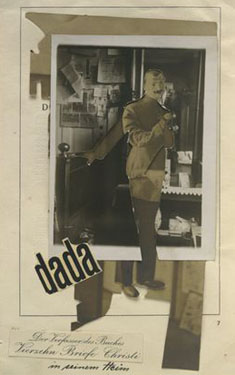

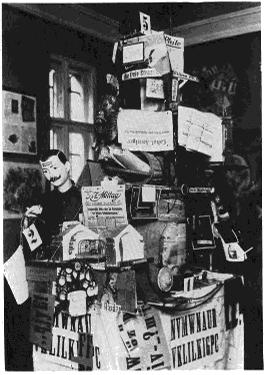

Johannes Baader (German, 1875-1955) The Author of the Book "Fourteen Letters of Christ" in His Home.

Johannes Baader (German, 1875-1955) Der Oberdada

Dada activities were also carried on in other German cities. In Cologne in 1919 and 1920, the chief participants were Max Ernst and Johannes Baargeld. Also affiliated with Dada was Kurt Schwitters of Hannover, who gave the name Merz to his collages, constructions, and literary productions. Although Schwitters used Dadaistic material—bits of rubbish—to create his works, he achieved a refined, aesthetic effect that was uncharacteristic of Dada antiart.