Zurich: The Birth of Dada

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection by IRENE E. HOFMANN. Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago

In February 1916, as World War I raged on, Dada came into being in Zurich in a small tavern on Spieglestrasse that became known as the Cabaret Voltaire. Founded by the German poet Hugo Ball and his companion, singer Emmy Hennings, Cabaret Voltaire soon attracted artists and writers from across Europe who fled their countries and went to neutral Zurich to escape the war.[2] Ball's cabaret provided ideal conditions for artistic freedom and experimentation and an atmosphere that supported the fomenting of revolt. A press announcement for the cabaret declared:

Cabaret Voltaire. Under this name a group of young artists has formed with the object of becoming a center for artistic entertainment. The Cabaret Voltaire will be run on the principle of daily meetings where visiting artists will perform their music and poetry. The young artists of Zurich are invited to bring along their ideas and contributions.[3]

Jean Arp, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco, Sophie Taeuber, and Tristan Tzara were among the artists and poets who responded and began gathering in Ball's Zurich tavern. From this diverse and passionate group, the Dada revolution was conceived and fueled. As German artist Hans Richter recalled, there was a highly charged atmosphere at the cabaret that united this diverse group in a common goal: "It seemed that the very incompatibility of character, origins and attitudes which existed among the Dadaists created the tension which gave, to this fortuitous conjunction of people from all points of the compass, its unified dynamic force."[4]

United in their frustration and disillusionment with the war and their disgust with the culture that allowed it, the Dadaists felt that only insurrection and protest could fully express their rage. "The beginnings of Dada," Tristan Tzara remarked, "were not the beginnings of art, but of disgust."[5] As Marcel Janco recalled: "We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again after the tabula rasa. At the Cabaret Voltaire we began by shocking the bourgeois, demolishing his idea of art, attacking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order."[6] Through uproarious evenings filled with noise-music, abstract-poetry readings, and other performances, Dada began to voice its aggressive message. While Dada evenings soon became notorious for insurrection and powerful assaults on art and bourgeois culture, it was through Dada journals that the news of this developing movement reached all corners of Europe and even the United States.

Hugo Ball was also responsible for the first journal directly associated with Dada. Launched in 1916 and named after his Zurich tavern, Cabaret Voltaire featured a conservative format with many illustrations and carried contributions by the Dadaists, as well as writings by Futurists and Cubists.[7] Literary works appear in either French or German, and in the case of a Huelsenbeck's and Tzara's poem "DADA," the two languages are interwoven. Through this review, published by the anarchist printer Julius Heuberger, Ball sought to define the activities at the cabaret and to give Dada an identity. In what turned out to be the first and only issue of Cabaret Voltaire, he wrote: "It is necessary to clarify the intentions of this cabaret. It is its aim to remind the world that there are people of independent minds—beyond war and nationalism—who live for different ideals."[8]

In 1917, after a year of Dada evenings and Dada mayhem, Cabaret Voltaire was forced to close down, and the Dada group moved their activities to a new gallery on Zurich's Bahnhofstrasse. Shortly after the closing of the cabaret, Ball left Zurich and the Romanian poet Tzara took over Dada's direction. An ambitious and skilled promoter, Tzara began a relentless campaign to spread the ideas of Dada. As Huelsenbeck recalled, as Dada gained momentum, Tzara took on the role of a prophet by bombarding French and Italian artists and writers with letters about Dada activities. "In Tzara's hands," he declared, "Dadaism achieved great triumphs."[9] Irreverent and wildly imaginative, Tzara was to emerge as Dada's potent leader and master strategist.

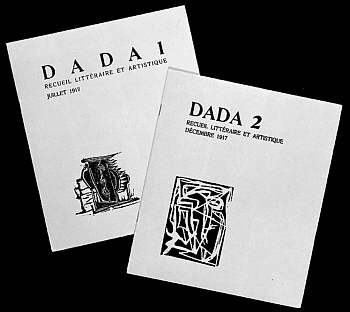

Dada 1, ed. Tristan Tzara (Zurich, July 1917), cover, and Dada 2, ed. Tristan Tzara (Zurich, December 1917), cover.

Attempting to promulgate Dada ideas throughout Europe, Tzara launched the art and literature review Dada. Although, at the outset, it was planned that Dada members would take turns editing the review and that an editorial board would be created to make important decisions, Tzara quickly assumed control of the journal. But, as Richter said, in the end no one but Tzara had the talent for the job, and, "everyone was happy to watch such a brilliant editor at work."[10] Appearing in July 1917, the first issue of Dada, subtitled Miscellany of Art and Literature, featured contributions from members of avant-garde groups throughout Europe, including Giorgio de Chirico, Robert Delaunay, and Wassily Kandinsky. Marking the magazine's debut, Tzara wrote in the Zurich Chronicle, "Mysterious creation! Magic Revolver! The Dada Movement is Launched."[11] Word of Dada quickly spread: Tzara's new review was purchased widely and found its way into every country in Europe, and its international status was established.

Dada 3, ed. Tristan Tzara (Zurich, December 1918), cover.

While the first two issues of Dada (the second appeared in December 1917) followed the structured format of Cabaret Voltaire, the third issue of Dada (December 1918) was decidedly different and marked significant changes within the Dada movement itself. Issue number 3 violated all the rules and conventions in typography and layout and undermined established notions of order and logic. Printed in newspaper format in both French and German editions, it embodies Dada's celebration of nonsense and chaos with an explosive mixture of manifestos, poetry, and advertisements—all typeset in randomly ordered lettering.

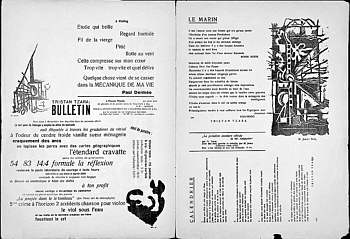

Dada 3, ed. Tristan Tzara (Zurich, December 1918).

The unconventional and experimental design was matched only by the radical declarations contained within the third issue of Dada. Included is Tzara's "Dada Manifesto of 1918," which was read at Meise Hall in Zurich on July 23, 1918, and is perhaps the most important of the Dadaist manifestos. In it Tzara proclaimed:

Dada: the abolition of logic, the dance of the impotents of creation; Dada: abolition of all the social hierarchies and equations set up by our valets to preserve values; Dada: every object, all objects, sentiments and obscurities, phantoms and the precise shock of parallel lines, are weapons in the fight; Dada: abolition of memory; Dada: abolition of archaeology; Dada: abolition of the prophets; Dada: abolition of the future; Dada: absolute and unquestionable faith in every god that is the product of spontaneity.[12]

With the third issue of Dada, Tzara caught the attention of the European avant-garde and signaled the growth and impact of the movement. Francis Picabia, who was in New York at the time, and Hans Richter were among the figures who, by signing their names to this issue, now aligned themselves with Dada. Picabia praised the issue:

Dada 3 has just arrived. Bravo! This issue is wonderful. It has done me a great deal of good to read in Switzerland, at last, something that is not absolutely stupid. The whole thing is really excellent. The manifesto is the expression of all philosophies that seek truth; when there is no truth there are only conventions.[13]

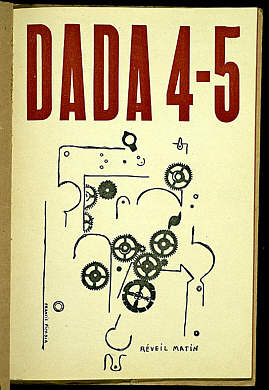

Dada 4–5 (Anthologie Dada), ed. Tristan Tzara (Zurich, May 1919), cover.

Dada 4–5, printed in May 1919 and also known as Anthologie Dada, features a cover designed by Arp, a frontispiece by Picabia, and published work by André Breton, Jean Cocteau, and Raymond Radiguet. This issue also includes Tzara's third Dada manifesto and four Dada poems Tzara called "lampisteries." Design experiments continue in this issue with distorted typography, lettering of various sizes and fonts, slanted print, and multicolored paper.

Issue 4–5 of Dada was the final one Tzara published in Zurich. With travel possible again at the end of the war, many of the Zurich group returned to their respective countries and Dada activities in Zurich came to an end. With the Dadaists spreading throughout Europe, the impact of the movement had only just begun. Huelsenbeck, Picabia and Tzara played principle roles in introducing Dada in other cities.

Berlin

Richard Huelsenbeck left Zurich in 1917 for Germany to initiate Dada activities and reconnect with the German avant-garde community that the war had scattered. In Berlin, the devastating years following the war were marked by unrest, rampant political criticism, and social upheavals. The stage was set for the emergence of a highly aggressive and politically involved Dada group. Dada in Berlin took the form of corrosive manifestos and propaganda, biting satire, large public demonstrations, and overt political activities.

In Berlin, Huelsenbeck met up with artists Johannes Baader, George Grosz, and Raoul Hausmann. While Huelsenbeck contributed greatly to the diffusion of Dadaist ideas through speeches and manifestos, it was Hausmann who ultimately emerged as one of Germany's most significant Dadaists. A painter, theorist, photographer, and poet, he became an aggressive promoter of Dada in Berlin. To establish his position, in June 1919 he began Der Dada, a short-lived yet powerful review that reflects the revolutionary tone of Berlin Dada. Contributions in the first issue by Baader, Hausmann, and Huelsenbeck declare the left-wing political agenda of Berlin Dada, while writings by Tzara and Picabia indicate the alliance between the Berlin group and other Dada centers.

The cover of the first issue of Der Dada, which was characteristic of Dada's intentional disorder and unconventional design tactics, features varied type styles and sizes, mathematical abstractions, Hebrew characters, and several nonsense words, all randomly ordered. Among this issue's phonetic poems and several abstract woodcuts is an outrageous—and bogus—announcement that those interested in learning more about Dada could visit the Office of the President of the Republic, where they would be shown Dada artifacts and documents. Such fabrications highlight the Berlin group's interest in satire, and their delight in infiltrating official government activities. The cover of the second issue of Der Dada further proclaimed the authority of Dada with the declarations that translate as: "Dada conquers!" and "Join up with Dada." This issue contains articles by Baader and artist John Heartfield as well as several collages by Hausmann, absurd faked photographs, and satirical cartoons by Grosz.

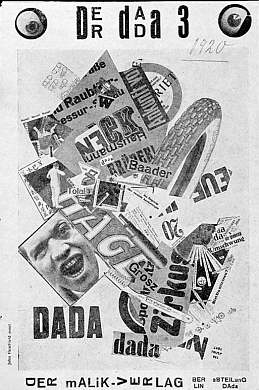

Der Dada 3, ed. Raoul Hausmann (Berlin, April 1920), cover.

Issue number 3 of Der Dada is one of the most visually exciting publications generated by the Berlin group. Edited jointly by Grosz, Heartfield and Hausmann (who signed their names "Groszfield," "Hearthaus," and "Georgemann"), the third issue of Der Dada was the most diverse issue yet, with several references to Dada in Cologne, Paris, and Zurich. The cover features a chaotic collage by Heartfield of words, letters, and illustrations. The issue includes a drawing by George Grosz, two montages by Heartfield, and photographs of the Dadaists, as well as cartoons, poetry, and illustrations.

Known for their rebellious and political tenor, it was not long before the Berlin Dada group members soon directed their aggressions at one another. With the eruption of many ideological clashes, by 1920 Dada began to decline in Berlin. Although sporadic publications appeared for a few years, by 1923 publishing had ceased, and the Berlin Dadaists began turning their attentions to other activities.